Plans to mitigate sources of investigatory risk and respond when an investigation does occur must change according to the risk profile of the business. Between novel technologies, evolving sensibilities and seismic shifts within industry, regulators and investigatory bodies are changing focus regularly. So too are business attitudes toward risk changing.

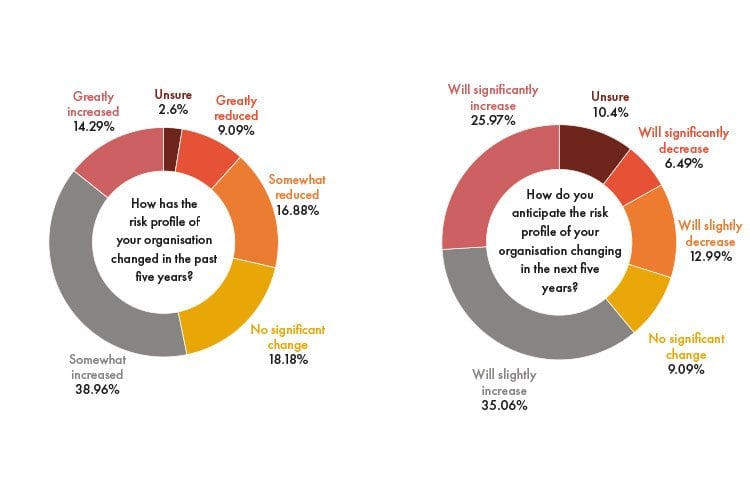

Generally speaking, when asked how the risk profile of their business has changed over the past five years, 53% of in-house counsel said it had at least somewhat increased. When asked to look ahead at the next five years, 26% felt that the risk profile of their business would significantly increase over the next five years, with 61% feeling that there would be at least a slight increase in their business’ risk profile.

When looking at changing risk profiles, data breaches are a good example: it wasn’t so long ago that the range of companies that rely on the collection and use of data was limited. Now, data has pervaded nearly every aspect of commerce. Retail stores that may historically have collected very little personal data now capture all manner of information at the point of sale for loyalty programmes, not to mention the continued recission of relatively anonymous brick-and-mortar buying in favour of online shopping.

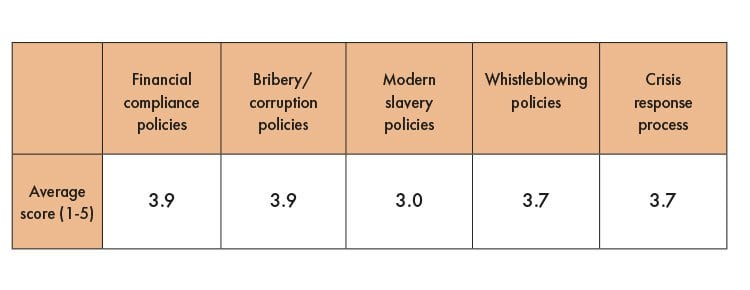

To go back further, increasingly globalised markets and supply chains have largely informed recent interest in modern slavery. Modern slavery regimes set an expectation that companies must not hide behind the strongest link in the compliance chain, instead being held accountable for the weakest link: a company in the United Kingdom may be perfectly above-board in a foreign jurisdiction, but regulators now hold those companies to the standard of UK law for their actions in jurisdictions further up the supply chain, where protections against abuse and exploitation are not as strong.

Reading the room

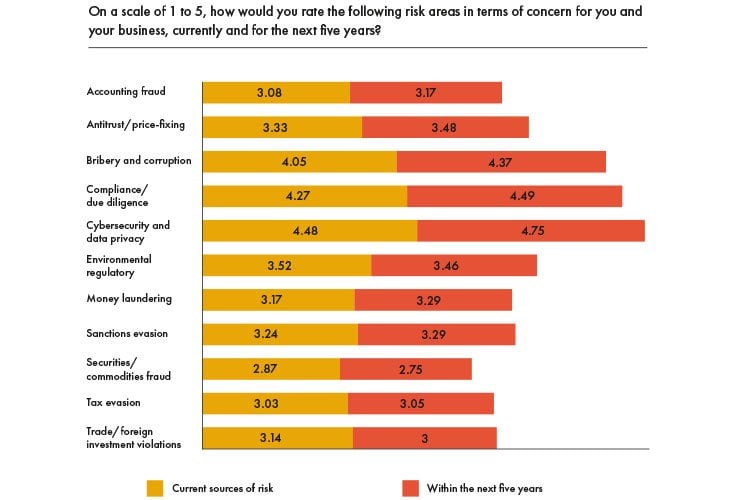

GC surveyed top in-house counsel from across the world, asking participants to rate their organisation’s current risk levels on a scale of 1 to 5, 1 being the lowest risk, and 5 the highest. The responses were broken up into the following categories:

- Accounting fraud

- Antitrust/price-fixing

- Bribery and corruption

- Compliance/due diligence

- Cybersecurity and data privacy

- Environmental regulatory

- Money laundering

- Sanctions evasion

- Securities/commodities fraud

- Tax evasion

- Trade/foreign investment violations

Cybersecurity and data privacy risks were rated as the highest concern by survey respondents, both in terms of the risk they currently pose to businesses and how that risk was expected to change in the next five years. Cybersecurity and data privacy risks were rated at an average of 4.48/5 currently, which ballooned to 4.75 when respondents were asked to look ahead at the next five years.

Compliance and due diligence are also top of GCs’ minds – both when speaking about their organisation’s current level of risk and when looking ahead to how this might change over the next five years – coming in at an average rating of 4.27 with an expected increase of 0.22 to 4.49 in the next five years.

On average, nearly every category is expected to become more risky over the next five years. Bribery and corruption risks polled the biggest jump, increasing by 0.32 points on the survey’s five-point scale.

Risking it online

With cybersecurity and data privacy almost unanimously rated as the most pressing risks for GCs both currently and in the coming years, many of the in-house counsel surveyed and interviewed for this report had much to say on the subject.

‘Cyber threats form one of the biggest security risks of the 21st century,’ said Ritankar Sahu, general counsel and head of compliance for the Maxpower Group, operating throughout Southeast Asia and the Middle East.

‘Most Fortune 500 companies have been victims to some form of cyberattack leading to economic damage ranging from a few thousand to a few billion dollars. Cyber-attacks have increased dramatically in the last few months amidst the pandemic.’

Until relatively recently, it might have made sense to talk about cybersecurity and data privacy in terms of specific sectors, but the adoption of mobile platforms and cloud services – be they for internal operations, customer interactions, or both – has made cybersecurity everybody’s problem. In fact, the sector in which a given survey respondent is working had virtually no impact on their perception of cybersecurity and data privacy as a risk: GCs working for manufacturing companies were just as worried as those working for healthcare providers.

This is something that Seshani Bala, general counsel at Chartered Accountants of Australia and New Zealand, has seen personally.

‘Another big challenge is that we are trying to give customers and members a personalised experience, and to make data-driven decisions as a business,’ says Bala.

‘So, we are collecting more data to focus on that personalised, segmented experience. That increases the potential privacy risks in the event of a data breach. The penalties are very high under GDPR and Australian law. We are now seeing other countries move to a mandatory notification system that is in line with GDPR standards, and this poses greater pressure on organisations to make sure they have robust policies and procedures to quickly comply with those notification requirements.’

‘With the rapid development of online services, the risks associated with data storage and cybersecurity will develop,’ agrees Roman Kuznetsov, legal manager at WILO RUS.

Bala has worked closely with stakeholders in the wider business to make sure data protection policies are both clearly understood and rigorously enforced.

‘Once we have made sense of that, we can then drive processes and controls to reduce risk in that space. We partner very closely with our IT team. I think that has probably been the biggest change I have seen the last 12 to 24 months. I think Legal and IT need to be best of friends in-house, and you really need an integrated approach to effectively manage risk in that space.’

‘Before moving to a digital solution, I think it is really key to understand how each platform stores, secures and moves data. Mapping out that data flow process and understanding the data risks and data journey, as well as how it integrates with other platforms or plug-ins in other locations is important. It’s a given that digital solutions need to comply with applicable privacy laws but legal technology solutions also need to appropriately protect legal privilege, corporate record holding, and in-house destruction and recovery policies.’

Modern working

While the large difference between current risk and expected risk over the next five years is undoubtedly a reflection of an increasingly data-driven world, the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic will certainly also be playing a role. With home working becoming near-ubiquitous over the past few months, the volume of data being transmitted – either from workstation to workstation, colleague to colleague or business to customer (and vice versa) – is at an all-time high. This, too, means that the scope for bad actors to gain access to confidential data is also higher than ever.

‘The effects of the pandemic, and the current situation the world is in, pose several challenges for us in terms of rearranging our fraud agenda,’ says Gustavo Sáchica, chief legal and compliance officer at Allianz in Colombia.

‘In-house legal counsel need to anticipate the possibilities of fraud under pandemic circumstances. At Allianz, we have measured and stressed our risk tests in order to consider as many possibilities as possible.’

‘Due to Covid-19, increased working from home has resulted in a rise of remotely-accessed work platforms and digital ecosystems,’ says Sahu.

‘This has made us highly dependent on technology which in turn has exposed us to more sophisticated cyber threats. For MAXpower, this has not been much different. Our fleet of gas engines are spread across remote sites in South Asia, and given applicable travel restrictions, we have had to rely extensively on our cloud based technology platform which lets us track ‘live’ operating performance, profitability and emissions from a centralised asset dashboard. The technology also lets us engage in predictive analytics and gives us valuable fleet-level insights.’

‘From a risk management perspective, I think the industry view is that enterprises still have lots to do before they can claim that they are breach-proof. MAXpower’s exposure is no less than other similarly placed power producers in the market.’

‘We constantly strive to make our systems less vulnerable to digital threats. As general counsel, I recognise that we are not breach-proof and regularly engage in conversations with our operations folks trying to gauge whether we are doing enough.’

For some in-house counsel worried about what the future might hold for their cybersecurity efforts, the risk is already eventuating.

‘We have also seen our mail servers being the victim of ransomware attacks and we have had to strengthen our firewalls,’ explains Sahu. ‘In the months to come, I am certain that companies will allocate more budget and resources to address cybersecurity risks, and I do see a rise in procurement of cybersecurity insurance coverage.’

Regulators

The interaction between the regulators’ attitudes to risk and the reality on the ground for in-house counsel is complicated. In some instances, regulators are leading the charge by focusing on an area of concern and proactively shoring up the relevant protections, or cracking down on non-compliant entities. On the other hand, regulators may have fallen behind the in-house community in how they approach these areas of concern. In this way, regulators can make a company’s compliance journey both easier and more difficult.

Khaled Shivji, chief legal officer at the UAE’s Moro Hub, highlights this point. ‘In order to reduce the regulatory cost of compliance, we would be grateful to see more proactive guidance from regulators and prosecutors about the kinds of risks they believe are rated by the national and state governments as risks that, if not tackled, will diminish the country’s overall international rankings concerning white-collar crime.’

‘Increased oversight by regulators is reshaping the way we approach risk,’ agrees Armando Cruz, director at KPMG in Mexico.

And as with everything, this dynamic between regulators and the market is being redefined by COVID-19, according to Maria Alvear, general counsel at Chile’s GASVALPO.

‘In my view, the whole landscape will change after COVID-19 crisis lowers its impact. It will probably remain within us for a while and that encourages us to change our old ways of working and doing business, including regulatory risk management.

‘Regulatory risk management has been very challenging during these months, with several regulations being issued due to COVID, so it’s hard to keep up-to-date and perform accordingly. I guess this uncertainty that we are facing will remain; sticking to regulatory compliance will become more important than it is today to avoid a situation where lack of control and uncertainty give space for corruption to enter the business.’