By any measure, the events of 2020 have been a remarkable moment in US history: an election that showed political divisions are more entrenched than ever, the type of civil unrest that had not been seen for decades, and in the midst of it all a global pandemic that exposed the fragility and inequality of the economy and prompted the US government to send cheques to 80% of the population. But it was the growing strength of the #MeToo and #BlackLivesMatter movements that really caught the attention.

‘Twenty years from now, sociologists will write books on the factors that coalesced to make this the moment when we finally sat up and acted as a nation’, comments Laura Quatela, senior vice president and chief legal officer of Lenovo. ‘There is a renewed focus on making real and meaningful change, and the kind of momentum that has not been with [US society] since the 1960s.’

As questions over racial equity rise to the top of the corporate agenda, diversity and inclusion (D&I) more broadly is being transformed from a feel-good story to a core part of business strategy. At the same time, says Hannah Gordon, chief administrative officer and general counsel with the San Francisco 49ers, consumers are becoming more willing than ever to sanction businesses that do not meet their expectations of corporate conduct.

‘Of course, 2020 [was] a very difficult year for everyone, but one of the lasting positives is that it sparked awareness of diversity, equity and inclusion inside major corporations. Business is waking up to the fact that we live in a world where a strong commitment to equality and justice is expected, and where the right thing to do ethically is the right thing to do in a business sense. The growing power of consumers to hold business to account is one of the really exciting developments to have taken place over recent months.’

And when it comes to holding the legal market to account, general counsel find themselves in a unique position to shape one of the least diverse professions of all.

The diverse dollar

To put it bluntly, the statistics on diversity within the legal profession are not encouraging. Figures from the American Bar Association show the profession is still as white- and male-dominated as it was ten years ago. Women now represent just 37% of active attorneys in the US, a slight increase from 31% in 2010, while black, indigenous, and other people of colour (BIPOC) lawyers account for just 14% of all active attorneys. In the most underrepresented groups, the number of minority lawyers has actually fallen since 2010.

It has not gone unnoticed by GCs. ‘We still get pitches from all white, male teams’, says Lenovo’s Quatela. ‘We just scratch our heads and think, did anybody look at the roster before they came? I’ve had the same conversation with my colleagues at other big tech companies, and we just don’t understand it.’

This, everyone agrees, is a situation that needs to change. But consensus on how to change it has been harder to come by. In 2019, US Representative Emanuel Cleaver led an open letter seeking clarification on how some of the largest tech businesses in the US were applying diversity policies and practices when hiring outside counsel. This rare moment of public scrutiny for the legal profession was also a timely reminder that those who pay the bills have the power and responsibility to introduce change. And with US corporations spending an estimated $70bn on legal services each year, the potential for their general counsel to drive change is huge.

‘The traditional response among corporate counsel has always been to consider the lack of diversity within law firms as a problem for law firms to address’, says Rishi Varma, general counsel and corporate secretary at Hewlett Packard Enterprise. ‘However, there is a growing sense among GCs that they, as buyers, are just as responsible for the slow pace of change within the profession.’

Jim Chosy, senior executive vice president and general counsel with U.S. Bancorp, has a similar take. ‘In-house legal departments have big role to play in positively influencing diversity with outside counsel. Given our purchasing power, we’re able to drive change and I feel an obligation to do this with our law firms, which we consider an extension of our own in-house function.’

But, as Varma cautions, pushing law firms to hire diverse candidates is only half the battle. Ensuring those candidates are given meaningful roles is just as important. ‘The question of diversity at law firms is a lot more complicated than headline figures. A firm or team can have impressive numbers around diversity – impressive, at least, when compared to other law firms – but that in itself does not mean progress is being made. The analytics I want to see are how many hours those diverse lawyers contributed to a matter. It is also important to understand how origination credits operate at law firms, and how merit and reward is assigned more generally. We need to move the conversation away from a simple focus on diversity toward a more nuanced understanding of how lawyers move through the ranks in their firms, and we need to accept that blaming law firms for a lack of diversity is not the solution – the situation is far more complicated than that.’

Moving the Needle

If the legal industry is going to tackle its historic diversity and inclusion problem, says Lenovo’s Quatela, general counsel and law firms will have to work together. ‘GCs typically have lots of ideas on how to improve things, but they have tight budgets. Law firms also have lots of ideas, but they have profitability targets. The only way to make any of these ideas happen is by finding a place where ideation and economic interests meet.’

One of the more notable attempts to formalise collaboration between law firms and clients has come from the Move the Needle (MTN) fund, an initiative launched by legal D&I innovation incubator Diversity Lab which has since been backed with $5m of funding.

‘There has been both a huge uptick in interest, and an increasingly sophisticated interest in D&I in the legal industry’, says Leila Hock, Diversity Lab’s director of legal. ‘Ten years ago, a law firm or legal department might have thrown money to sponsor a table at an event. Now they recognise that window dressing is not enough. [D&I] is a real issue for the industry and structural and systemic changes that are required. That is a positive development. I finally feel like we are having the conversations with lawyers that many of us in the D&I space have been having among ourselves for years.’

The initiative has brough together law firms, general counsel, and community leaders to road test diversity initiatives and develop new approaches to overcoming underrepresentation which, says Hock, ‘will hopefully serve as models for lasting change.’

For many of MTN’s founding GCs, the biggest draw is its uniquely experimental nature which fosters innovation in a way that many firms or in-house departments cannot do alone, especially when it comes to financing. ‘One of the big pillars of what we are trying to achieve is the type of collaboration that hasn’t happened before in the legal industry’, says Rishi Varma, a founding member of MTN. ‘By talking and brainstorming as a group, GCs and law firms are finding non-traditional ways of brining diverse lawyers into the profession.’

While the initiative is still in its early days, fellow MTN member Laura Quatela is encouraged by the early results. ‘We are at the point of whittling down the ideas to some initiatives that we as a group want to line up behind. One of the things we’ve talked about doing is a combined law firm and in-house summer programme, where interns or clerks have the opportunity to experience both worlds early in their training so they can start to make the important decisions about where they really want to end up. Other ideas are more experimental. For example, we have been thinking about how legal teams can hire a firm’s top diverse candidates for a set period of time to help them get a solid grasp of how a business operates and what it wants to see from its lawyers. That’s what MTN is all about. It’s a laboratory for experimentation that gives lawyers committed to D&I the chance to do something new.’

For law firms and businesses alike, coming up with new ideas to improve diversity and inclusion is likely to become one of the biggest challenges of the years ahead. ‘What we absolutely don’t want to do is waste the momentum for social change that exists right now’, says Hock. ‘In response to the reawakened racial justice movement we are tracking the public statements made by the large law firms and Fortune 100 companies have made. We are going to track them and check back to see if they’re doing what they said they would do. And we are not the only ones doing this. We need to make sure that companies don’t just put out a statement or put a pride flag on their logo – they need to take action.’

Finnegan – The Legal 500 View

Ask Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner, LLP’s clients and you’ll hear praises of its professionalism, its technical expertise, and its ethics and integrity. And if you look to The Legal 500 you’ll find that Finnegan has been the strongest performer in its class for over a decade of coverage. This piece is a quick look at a firm that has been one of the most high-quality legal outfits in its field. It’s not one of Manhattan’s white-shoe firms, and it’s certainly no jack of all trades. Finnegan brings a level of expertise and dedication expected of a specialist boutique, but with well over over 300 IP professionals firm-wide, Finnegan is unique. A mega-boutique that is one of the most dominant players in the IP market, Finnegan, Henderson, Farabow, Garrett & Dunner, LLP is among the most consistently excellent firms in any one field of practice.

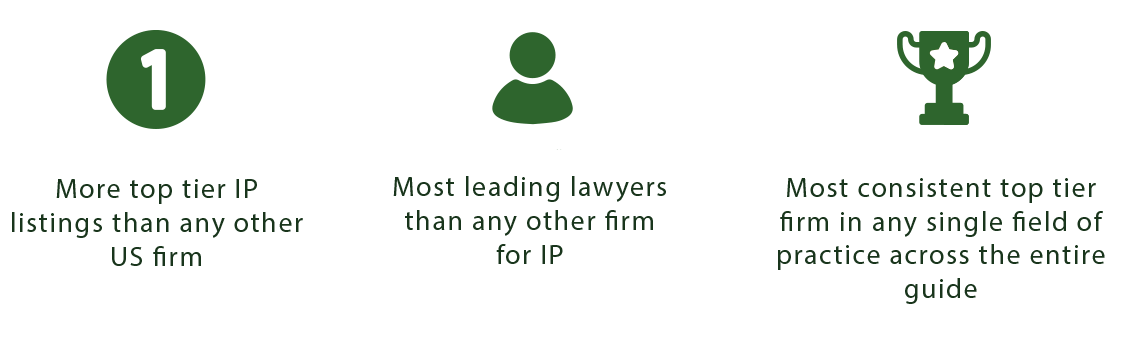

To illustrate the point, let’s look at a few statistics. With six tier 1 rankings in the US 2020 guide, Finnegan earned more top-tier IP listings than any other US firm. Finnegan’s rankings in those six tables tell us at least three important points about the firm. First, Finnegan has shown itself to be the market’s most complete firm when it comes to registered marks. The firm is ranked among the market leaders in each of the US guide’s four patents tables, as well as in both of the trademarks tables. What’s more, these rankings indicate another kind of breadth of service that is unparalleled in the US IP market. There are some firms that are known far and wide as fierce IP litigators. Other firms—often those with wider strengths in corporate and tech sector-work—have gained a reputation for high-value licensing deals and IP-heavy transactions. Finnegan, however, is the only firm with such compelling highlights in all areas of IP litigation, IP transactions, prosecution, and IP management, both for trademarks and patents.

There’s no question that Finnegan was an impressive performer in the 2020 guide, but the most impressive stat is this: Finnegan has been leading in every one of these six categories for the past five years. In fact, with the exceptions of two small blips (one in 2009 and another in 2015), Finnegan has been a tier 1 performer in every patents and trademarks ranking since the inception of the US guide. To be clear, even those two “blips” amount to dropping to tier 2 in two categories for one year each. Certainly, it’s been a long time at the tops of the tables.

Finnegan is unique in the IP market. But from a rankings perspective, Finnegan is actually the most consistent top-tier firm in any single field of practice across the entire US guide. For each of the past five years, Finnegan has scored six tier 1 rankings in the field of IP. Look to the rankings data for the areas of Finance, Dispute Resolution, M&A/corporate; there is no other firm in any single practice area that has recorded as many top-tier rankings in as many year as Finnegan. From a Legal 500 rankings perspective, and judging firms by a single core expertise, Finnegan is arguably the very best firm in the US market.

Our primary focus at The Legal 500 has always been ranking teams as a whole; but we do of course also put a lot of effort into recognizing the individual lawyers who really stand out. Some Finnegan veterans like Reston-based patent litigator Charles Lipsey have featured on the Leading Lawyers list for about a decade. Among the bearers of the firm’s legacy, Lipsey was first ranked just a couple of years after the US guide was founded, but has been with Finnegan since 1978. Lipsey stands out in particular as being one of the guide’s Hall of Fame Lawyers: a ranking that recognizes an individual’s long-standing and continued position as a leader in their legal field. At the other end of the spectrum, The Legal 500 ranking data also confirms Finnegan’s ability to attract and develop younger talent.

For many years The Legal 500 had identified the best-known and most experienced lawyers in each field of practice. Then in 2017, the US guide introduced a ranking category called Next Generation Partners, designed to shine light on future stars; market leaders of a new generation. In the year that ranking was introduced, Finnegan scored an impressive five Next Generation rankings. No other firm notched more Next Generation Partners in the IP section. Perhaps even more impressive is that of those five lawyers, three went on to become Leading Individuals at the firm. Two years after the establishment of the Next Generation Partners list, The Legal 500 introduced a category called Rising Stars, which aims to highlight promising associates in the market. Again, in its very first year of consideration, Finnegan recorded a name on the Rising Stars list. It might come as no surprise that in sheer numbers, Finnegan has more Leading Lawyers (e.g. Leading Individuals, Next Generation Partners, and Rising Stars) than any other firm in the IP rankings.

Across several points of comparison, Finnegan has been one of the strongest firms in The Legal 500 US over the last decade. The focus here has been on the firm’s top-tier rankings, but it’s also worth noting that Finnegan is featured in The Legal 500 US’ Trade Secrets category, and has also been highlighted in the Copyrights section. Finnegan is perhaps the most complete IP firm in the US, and with a strong roster of Leading Individuals—from stalwart Hall of Famers to Rising Star associates—the firm seems set to maintain its place at the top for years to come.

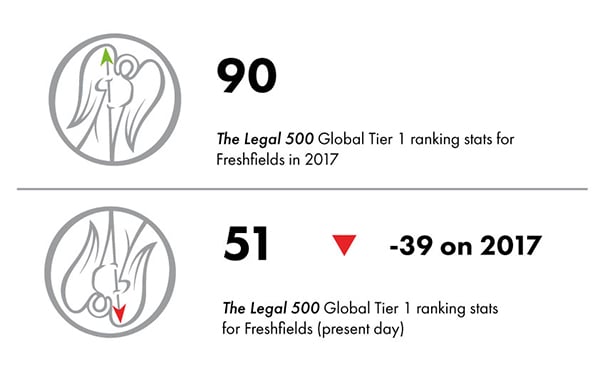

Traditionally, ethics and law go hand in hand. Law firm partners should have an innate moral compass. On that basis no distinction should be necessary between legally sound and morally or ethically justifiable advice, and for corporate counsel this distinction should not play a role either when mandating a firm. Ethics committees and supervisors should therefore – in theory – be superfluous. But that traditional approach is now seen as old-fashioned and incompatible with some aggressive profit-driven clients demanding aggressive profit-driven solutions. The danger for any law firm is that it is obliged to adopt the moral compass of its important (high-profit) clients and place money-making over traditional ethics. That is a problem that faces all major firms, not just Freshfields, although it is Freshfields that is providing a case study in how high-profit work can come at a reputational cost.

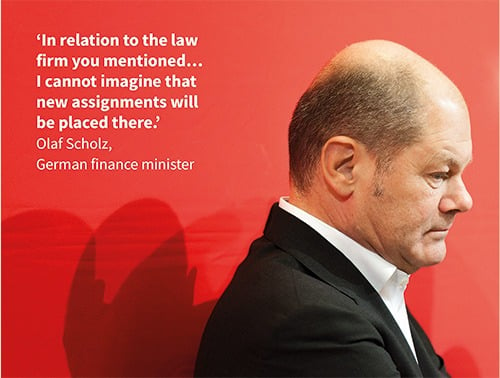

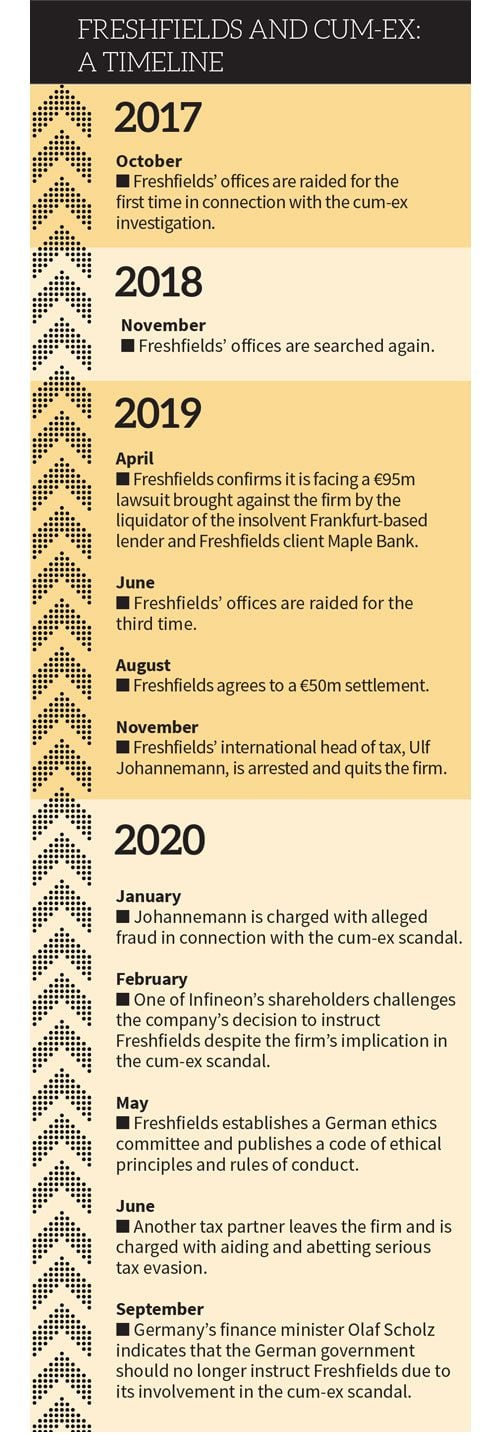

Traditionally, ethics and law go hand in hand. Law firm partners should have an innate moral compass. On that basis no distinction should be necessary between legally sound and morally or ethically justifiable advice, and for corporate counsel this distinction should not play a role either when mandating a firm. Ethics committees and supervisors should therefore – in theory – be superfluous. But that traditional approach is now seen as old-fashioned and incompatible with some aggressive profit-driven clients demanding aggressive profit-driven solutions. The danger for any law firm is that it is obliged to adopt the moral compass of its important (high-profit) clients and place money-making over traditional ethics. That is a problem that faces all major firms, not just Freshfields, although it is Freshfields that is providing a case study in how high-profit work can come at a reputational cost. Whether flawed culture has afflicted Freshfields is uncertain, but the danger for the firm is one of perception: whether those two malefactors are seen (fairly or unfairly) to indicate a deeper-seated problem in the larger organisation. At the very least, the crisis poses questions over internal checks and balances. The GC at a US retail company makes a blunt assessment: ‘The firm’s role in the scandal must be made clear and there needs to be a statement about the firm’s values, to which it will adhere in the future.’ Freshfields’ May 2020 code of ethical practice might have sought to answer the second part of this, but the risk for the firm is that it is seen as no more than a belated PR exercise to try to distance itself from the ongoing bad publicity without directly confronting the part it played in cum-ex matters.

Whether flawed culture has afflicted Freshfields is uncertain, but the danger for the firm is one of perception: whether those two malefactors are seen (fairly or unfairly) to indicate a deeper-seated problem in the larger organisation. At the very least, the crisis poses questions over internal checks and balances. The GC at a US retail company makes a blunt assessment: ‘The firm’s role in the scandal must be made clear and there needs to be a statement about the firm’s values, to which it will adhere in the future.’ Freshfields’ May 2020 code of ethical practice might have sought to answer the second part of this, but the risk for the firm is that it is seen as no more than a belated PR exercise to try to distance itself from the ongoing bad publicity without directly confronting the part it played in cum-ex matters.