‘Bureaucracy is the death of any achievement.’ – Albert Einstein

Or is it? Perhaps ask a Brazilian – they tend to know a thing or two about bureaucracy.

‘It’s a very specific problem we have here in Brazil because we are a huge country – we have over 5,000 cities and each one of these cities has at least three different institutions from which it is possible to get different documents. Institutions like the city hall, the labour department, the justice department, the environment department, or the federal government,’ says Pedro Roso, CEO and co-founder of Docket, a legal tech start-up.

And the legal sector itself, says lawyer and tech entrepreneur Bruno Feigelson, is as swollen and filled with complexity as it could be. According to Feigelson, Brazil spends 2% of its GDP on its legal system, and there are currently 100 million ongoing lawsuits in the country.

‘If you compare that with our population – we have 200 million people – we have one lawsuit per person, because you have the plaintiff and also the defendant,’ he explains.

Discontent? Disaggregate

Felipe Monteiro is professor of strategy at INSEAD, and is also the academic director of the Global Talent Competitiveness Index, which identifies the world’s most talent-competitive countries. This has led him to look at how companies and sectors around the world are being transformed.

‘I remember talking to the CEO of a very large, fast-moving consumer goods company in Brazil. This is a very marketing intensive company, and the CEO said: “Brazil is the only country in the world where we have more lawyers than marketing people.”’

All this means one thing for start-ups armed with the technology to bat away reams of paperwork and administration: opportunity.

‘If we go to the legal sector, what’s happening is that whereas one company used to have a full range of activities, a lot of start-ups are coming and trying to break down the full service into smaller parts,’ explains Monteiro.

‘If you think about utilities, BT Group had the full service but now a lot of start-ups are saying “Maybe we can use the infrastructure of BT but start offering different things.” You can think about this as different technologies, but I think most of all, it is not about that. It is that you as a person now have different needs. Maybe an incumbent used to give you all those options, but now independent players can use the infrastructure and offer you different paths, maybe in a more efficient and effective way.’

One company aiming to apply this model to in-house legal teams and unbundle internal processes is ProJuris, a start-up currently enjoying its tenth anniversary.

‘There are more than 1.2 million lawyers in Brazil, which has led to one lawyer for every 190 Brazilian citizens,’ says digital marketing manager Tiago Fachini.

‘we have huge potential, because we have opportunities with sectors inside of the legal system.’

‘Our purpose is to eliminate inefficiencies of the legal routine. We are working with AI in several ways to help lawyers to be more efficient and happy. We are also working with automation and some very neat integrations.’

The company’s SaaS (software as a service) product automates repetitive activities, like creating or updating cases, creating documents, or distributing and managing team tasks. ProJuris also offers software to corporate legal teams designed to improve productivity of the teams who work with contracts, documents, signatures and requests from internal clients. It claims to have more than 1,800 customers, with over 20,000 lawyers using ProJuris every day.

Another is Docket. Founded in 2016, the self-proclaimed ‘document shop’ has developed a platform on which clients – for example, the legal departments of large companies – can manage documentation, allowing faster access to documents, reduced friction with public services and AI-enabled data analysis. Last year, the company participated in Google’s Launchpad accelerator programme.

‘The size of this market is huge. We used to operate without any technology and now we are looking for how technology could solve a lot of problems, through automation or AI and, with this market size, with this very complex system and with technology, I think we have the recipe to create a lot of start-ups in this market,’ says Roso.

‘In Brazil, this year [2019] was the year of fintechs. But I think the legal techs in the next two or three years will be the hype of the year, because we have a lot of solutions emerging. And we have huge potential, because we have opportunities with sectors inside of the legal system.’

Innovation by association

Someone who certainly believes in the future of legal techs is Bruno Feigelson. A lawyer himself, he founded his own legal tech company in 2016, Sem Processo, which aims to connect lawyers and companies in order to resolve and settle the vast numbers of matters that end up before Brazil’s legal system more easily.

But he didn’t stop there. The following year, together with legal departments and law firms, Feigelson – who also runs a law firm, a law school and a legal tech accelerator – created the Brazilian Association of Lawtechs and legalTechs, known as AB2L.

‘At that moment, we had some tech companies in Brazil, but we didn’t have the main legal tech or law tech – it was something like a desert in Brazil for technology. We started the association with just two companies and, nowadays, we have 200 legal techs in Brazil in the association,’ he explains.

Feigelson had observed an increasing interest in technology to assist in legal processes such as contract automation and litigation management and analysis, and he predicted this would evolve beyond the implementation of tech solutions developed in-house to the use of external platforms and processes that would become available on the market. And he is confident that he was right.

‘We have a lot of potential. It’s very interesting because the biggest change is not just the technology – it’s the change of mindset,’ he says.

‘Lawyers are now looking to find a newer way and a better way to change the field. It’s interesting to compare AB2L two years ago and now. Now we have solutions for tax, for compliance and for data protection.’

One particular area of innovation observed by Feigelson is visual law – using design to illustrate legal documents.

‘The biggest lawsuit in Brazil is one in which the state of Brazil is suing certain companies. This lawsuit could be worth billions and billions of dollars. We are drawing all the petitions in order to help the judge show the court what has happened. Three years ago it was impossible to imagine that you would be in a meeting with a lawyer and a designer to improve understanding for the client,’ he says.

‘the biggest change is not just the technology – it’s the change of mindset.’

But, he concedes, this has not yet translated to a huge number of legal tech companies in Brazil currently.

Growing pains

Roso believes that coming up with an idea for a start-up in the legal sector, particularly in Brazil, necessitates first-hand experience of the market. Docket itself was created following the challenges experienced by one of the co-founders while working for a real estate company.

‘You need to study a lot to create a start-up to solve these processes. It’s different to thinking “Oh, let’s think of something to create.” I think for legal tech you need to experience this pain, you must understand how to solve it. It’s not too simple because we don’t have a standard here,’ he says.

Put simply, however, Brazil is not the most conducive environment in which to open up a business. Placed 138th out of 190 countries included in the World Bank’s Doing Business 2020 rankings for starting a business, the country scored 124th for ease of doing business overall (figures taken from World Bank. 2020. Doing Business 2020. Washington, DC: World Bank. DOI:10.1596/978-1-4648-1440-2. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO).

‘The complexity to open a business, get clients, handle these physical problems that we have to understand our taxes, to pay our taxes – I think it’s not so good yet,’ says Roso.

For the legal sector, there are specific problems, and the very bureaucracy that has created a huge potential market for legal technology platforms also creates hurdles.

‘We have the problem of dealing with hundreds of different courts around the country, each one with its own system. There are more than 100,000 open cases in the Brazilian legal system, so in this decentralised and unstructured scenario, most legal techs fail to obtain and use public information,’ says Fachini.

The Doing Business website identifies some business reforms made by the governments in recent years that have smoothed the way for those looking to start a business. These include speeding up business registration, lowering the cost of the digital certificate, and establishing online systems for company registration, licensing and employment notifications for Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. The government also launched an online portal for business licences in Rio de Janeiro.

‘I think this government, and other governments, are concerned with being more friendly with entrepreneurs. As a result, we have had laws pass through our congress that make it easier to be entrepreneurs,’ says Roso.

‘We are at the beginning of this agenda. It’s a long ride – we have a lot of things to do, but we are starting, so this is something to celebrate: we start this process here. I think the support from the government is very important because they could transform this whole scenario and bring more investment to our country and generate more jobs. Everyone has some kind of benefit from that.’

A new (ad)venture

The biggest problem, according to Feigelson, is a lack of investment relative to markets such as the US or the UK.

However, the tide may be beginning to turn in the venture capital stakes. In 2019, SoftBank Group launched a $5bn technology innovation fund focused on Latin America. In May 2019, Crunchbase reported that venture funding in Brazil reached $1.3bn in 2018, up from $859m in 2017 and $279m in 2016, according to figures taken from LAVCA, the Association for Private Capital Investment in Latin America.

‘[Venture capital funds] are more present in Latam, I think, compared to three or four years ago – when it was completely different,’ says Roso.

Perhaps a cautious approach to investment among incumbents is prudent.

Closer to home, in the legal sector, encouragement for legal tech is not as evolved as it could be, says Feigelson, whether through direct investment or by launching incubator and accelerator programmes. Early adopters are often thin on the ground, and although support is there in theory, the money is not always where the mouths are.

‘The law firms in Brazil, they don’t invest a lot of money in law techs. They don’t have a lot of money, because in Brazil we have a closed system in law firms. It’s impossible to invite a partner that is not a lawyer to introduce to this society,’ he explains.

‘They believe, but they don’t believe in this revolution. It’s very common that I’m going to a conference and talking about international big law and the companies that they are creating. But the Brazilian law firms, they are not doing the same.’

Adds Fachini: ‘Sometimes, our Brazilian bar association (called the OAB) puts some barriers in the technology way, trying to keep the old patterns instead of helping us to develop faster to help even more people.’

Perhaps a cautious approach to investment among incumbents is prudent, however. To throw a potential spanner into the trend among law firms in regions like the US and Europe to launch innovation labs, Monteiro believes that the benefits to incumbents of incubating and/or accelerating start-ups are not always clear.

‘It’s not even a billion-dollar question but a trillion-dollar question: to what extent incumbents will ever be able to integrate whatever those start-ups are doing,’ he says.

‘Imagine I’m a big company, let’s say a bank, and I start investing in fintechs – I have all those fintechs in my lab. To what extent will I be able to change the bank, or will I just be an investor in those new things? It’s not trivial, because the nature of the change is so much more profound than the previous technological changes.’

Monteiro is not speaking specifically about the legal sector, of course, but of a general response to possible technological disruption across the board.

‘I think we have a tendency of thinking that this idea of open innovation and accessing business technologies is more about “How do I connect with start-ups?” But actually, a lot of my feedback about it is that it is not about the connection itself, it’s more about “How do you bring those things home? How do you transform the mothership?”’

But Feigelson has observed the tech revolution (and, perhaps, cultural invasion) continuing apace – across all sectors in Brazil, even legal. And in-house teams, with their proximity to trends across the corporate ecosystem, are well-placed to benefit.

‘In Brazil, if you are a bank you are looking for fintech, if you are a health company you are looking for health tech – all these companies are living a special moment. We have a big movement in Brazil against wearing a tie, nobody wants to wear ties, they want to be modern, they want to be like Steve Jobs,’ he says.

‘The reconnection of the legal world with this new reality, of the fourth industrial revolution, it’s easier for legal departments than the law firms.’

In-house leading the way

‘there is no way back – technology will only be more and more relevant to the legal market.’

‘[Incumbent legal service providers] are starting to realise that technology is a friend which can help them to be more effective and efficient in their daily activities. In the beginning, there were misunderstandings about how technology would and could help, but now everyone is looking for tools to help legal routine,’ says Fachini.

But, in many cases, according to Feigelson, customers are coming from the in-house sector, and not external firms: ‘They take the money that was for the law firms and they put it into legal techs.’

At Docket, most clients are also tech-curious in-house departments. Their concerns are practical rather than innovation-related, in Roso’s view.

‘We have 130 people here, we have a huge team, and we always talk with huge clients, so we need to be prepared to absorb these huge clients. I think their consideration, at the end of the day, it’s not about [whether we are] a start-up, but if we will have the necessary structure to handle them. I think, in most cases, they are very optimistic about how technology could transform the legal department and reduce these operational jobs without any kind of value,’ says Roso.

The Brazilian general counsel GC spoke to as part of the research for this report were bullish about the potential of technology to improve in-house life, and took a pragmatic approach to the adoption of innovative tools – whether they be those developed specifically for their own departments, customised off-the-shelf software, or services procured from third-party tech providers.

‘Legal tech is the future; it is only a matter of time before they can prove what they are using is consistent and sustainable. I think that there is no way back – technology will only be more and more relevant to the legal market,’ says Rafael Dantas, director of legal and compliance in Latin America for General Mills.

For some, the challenges around technology revolve not only around selecting system tools likely to be effective, but identifying the best method of procurement. General counsel must find the right momentum and timing between developing them internally (balanced with other priorities within companies) and hiring third-party developers. But, the need for appropriate system tools is widely accepted.

Is disruption coming?

Conditions are certainly favourable in Latin America – and in Brazil specifically, says Monteiro.

‘When you are a developing market, one potential application of technology is offering leapfrogging opportunities. Remember that in a number of these markets they have nothing, and if they adopt the most recent technology, they will basically skip prior stages of technological development. The most well-known case was in Africa with M-Pesa in Kenya where, 10-15 years ago, most people didn’t have a bank account. M-Pesa started offering mobile payments on very simple phones. Many Kenyans don’t have a formal bank account and maybe they never will, because a lot of people skipped and started having a mobile wallet in their cell phones,’ he says.

‘There are a number of examples like this in Latin America. If you want to extrapolate a little and think about the legal sector, there are maybe two points to consider: one, is to imagine that some companies, and some of those start-ups, will never engage with formal legal services as we know them now – maybe they will skip that and they will start engaging with new ways of getting legal services; two, is the level of complexity of the Brazilian legal system – it is so complex, which means that you have a lot of lawyers and that’s why the legal tech sector in Brazil is thriving – because people know that there will be ways of disrupting that market and offering many different things.’

Feigelson certainly knows, and perhaps his enthusiasm – and that of the legal techs, like Docket, which is an AB2L member – will continue to be catching.

‘We believe a lot that we have the numbers and we have the anthropological conditions to make the biggest evolution in technology in Brazil. I work with researchers in Brazil, I work with law techs from other countries: people are coming to Brazil and trying to understand what’s happening here. I think we have a lot of change.’

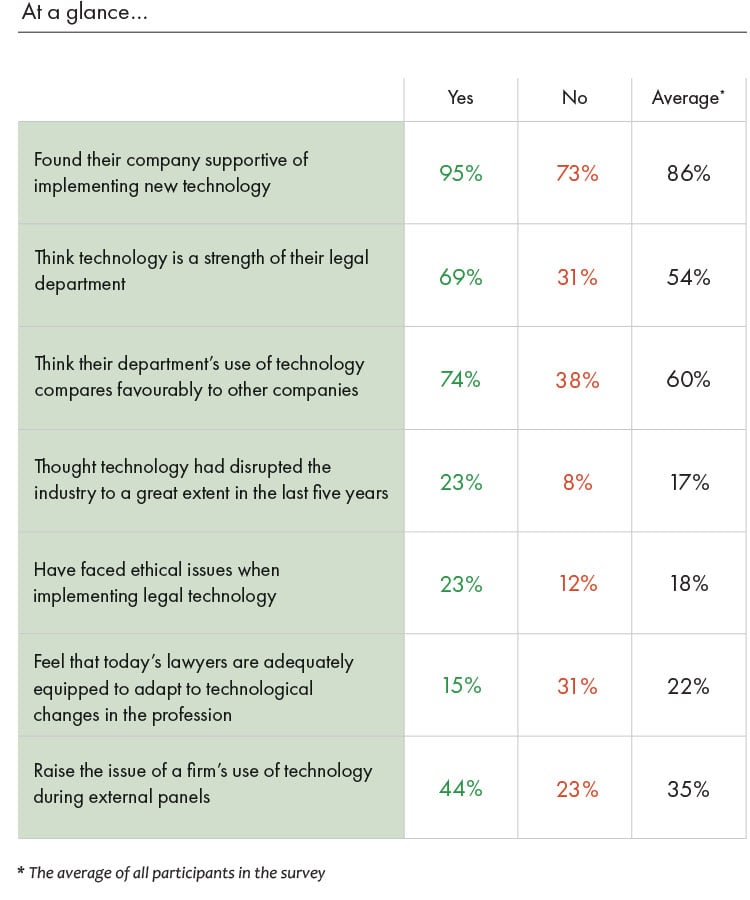

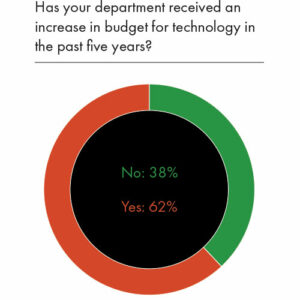

Making a first foray into legal tech can be a daunting experience for some legal departments. For a profession that (whether fairly or not) retains the reputation of being technological luddites, having the support of the wider organisation when taking the first steps with legal tech – or expanding on a positive start – can make all the difference, according to the in-house counsel that participated in our research.

Making a first foray into legal tech can be a daunting experience for some legal departments. For a profession that (whether fairly or not) retains the reputation of being technological luddites, having the support of the wider organisation when taking the first steps with legal tech – or expanding on a positive start – can make all the difference, according to the in-house counsel that participated in our research.