There are some things in life that don’t seem quite right when put together: take Jerry Hall and Rupert Murdoch, everything about Donald Trump and the presidential race, kids and matches, high heels and a nice polished floor. Another awkward anomaly is the procurement department sidling up with in-house legal and attempting to make nice.

GC Powerlist: Mexico

In a world experiencing both economic and political upheaval, North America remains a relative bastion of stability and prosperity globally, with Mexico playing an increasingly important role. Economic growth in particular has been steady, with the International Monetary Fund ranking Mexico as having the 11th highest GDP in the world based on purchasing power parity, and the fifth largest of the ‘emerging markets’ behind China, Brazil, Russia, and India. Trade agreements and a string of key reforms have contributed to the success of the economy, gradually dismantling the perception of Mexico as a third world nation plagued with powerful drug cartels and mass migration to the U.S.

Riding the wave: how engaging with corporate sustainability can help GCs to demonstrate value

GC: Can you tell me about the UN Global Compact and what ‘sustainability’ means for businesses?

Ursula Wynhoven (UW): The Global Compact is the UN’s corporate sustainability initiative. ‘Corporate sustainability’ in this context means the creation of long-term value by businesses in four dimensions: in economic, social, environmental, and ethical or governance terms.

Perfect panelling for the post-public post

Royal Mail is rather like Unilever House, the grand 1930s neoclassical Art Deco building it inhabits on the north side of Blackfriars Bridge. From a distance, it is impressive, monolithic, inspiring nostalgia yet leaving the observer with a twinge of concern about whether such an edifice can survive the ravages of the modern world.

Continue reading “Perfect panelling for the post-public post”

What 18 years in-house taught me about how to advise clients

In late 1998, I stepped onto the seventh floor of Eleven Madison Avenue in New York City. I was interviewing for a job in the litigation group at Credit Suisse First Boston. At the time, I was an assistant United States attorney, thoroughly enjoying my in-court experience and proud to be representing the U.S. government in the federal trial and appellate courts. But my wife and I were expecting a child and we had just bought a house. It was time to find a job in the private sector.

Continue reading “What 18 years in-house taught me about how to advise clients”

GC Roundtable: Business as usual? Middle East

With a fall in commodity prices prompting fiscal pressures for businesses around the globe, it comes as no surprise that companies in the oil-rich Middle East are feeling the financial pinch. While a number of those in attendance were bullish about medium- term prospects, with factors like the lifting of sanctions and opening up of Iran to trade cited as reasons for optimism, the short-term was undoubtedly a more challenging time with cost pressures a topical issue, irrespective of sector.

Continue reading “GC Roundtable: Business as usual? Middle East”

Focus on… Xerox

In 1981, Xerox devised and released the first computer (though Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace might well disagree on this point) which took only four hours to master the basics of, and cost a tidy $16,595. It even had an ‘unusual control device’ – or, as we like to call it these days, a mouse.

Who do you want to be?

I meet and spend time with many GC’s from both large, and not so large, organisations. It can be an enriching experience, and though I’ve had the odd crippling disappointment, I enjoy the learning I always gain. Let’s face it – these are, quite frankly, privileged interactions. Recently I had a meeting with a highly respected and well-regarded GC who leads the legal function for a major FTSE 100 company. I hadn’t spoken with them before and had been looking forward to our meeting, as they’ve been written about by others and identified as a role model for those in-house. It took an age to get access and then to finally get the meeting scheduled. To say I was filled with anticipation would be an understatement.

Being uncomfortable

Any kind of change is a hard and often emotional process. There is generally a certain amount of challenge and even discomfort involved.

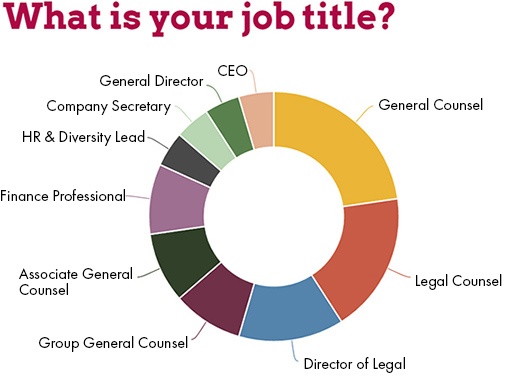

Quantitative research analysis

In order to make the survey representative of the UK economy, we collected responses from a variety of job titles, a cross section of industries and a range of small and large companies. The vast majority of our respondents (62%) are legal professionals: with general counsel, legal counsel and director of legal being the most prevalent job titles. The non-legal respondents in our survey sample had a good understanding of both their own legal department and the external legal services market – with respondents typically working within the c-suite or human resources.

In-house diversity: strategies and challenges

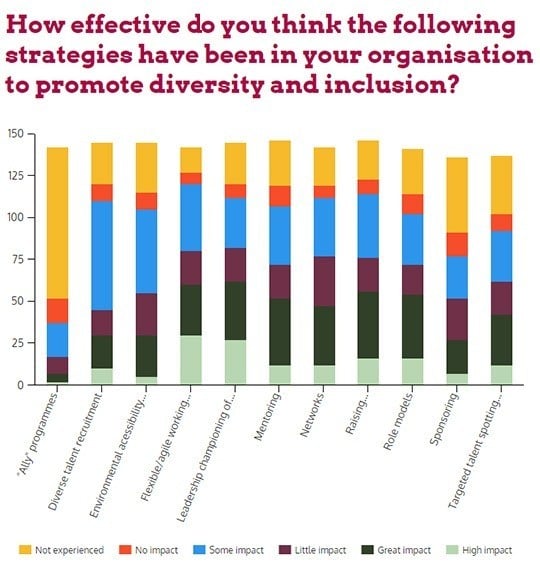

As society is becoming increasingly aware of the need for diversity; companies seeking better results and an advantage over their competitors must have a workforce that reflects the progressive shift taking place in the wider market. Research has shown that diversity contributes to better corporate results, greater innovation, and increased profits, making companies with diverse teams and leadership better positioned to compete in the current market. It is not surprising, therefore, that an overwhelming majority of organisations in the UK have formulated diversity plans that draw upon an array of both proven and newly formulated strategies. To examine the success of both old and new approaches, we asked our participants how effective they thought specific strategies were for promoting diversity and inclusion within their companies.

Our respondents overwhelmingly saw leadership taking a role in championing diversity, and flexible working practices as the two strategies which produced the best outcomes. These two had the highest proportion of participants reporting great or high impact on the levels of diversity and inclusion within the organisation. In contrast, out respondents saw recruitment and promotion strategies – covering approaches including diversity talent recruitment, targeted talent spotting and leadership development, as well as the sponsorship or diversity programmes, and the use of physical and environmental accessibility, as the least effective. It is worth noting however that some of these strategies are quite progressive and may not have taken hold in many organisations yet.

What’s in the future?

To assess the wide reaching dimensions of diversity we asked our survey participants where they believe future challenges for diversity lie. Interestingly, the distribution of responses was similar across most categories, illustrating that the concept of diversity is not specific to one challenge or segment of society. Gender was the most prevalent area of focus for our respondents (21%), followed by social mobility (17%), ethnicity (15%), mental health issues (14%), disability (14%) and LGBTQA (8%). At just 2% of total responses, age was the most under-reported challenge, perhaps reflecting the fact that most companies are already highly diverse in that respect.

What can in-house legal teams do to encourage diversity?

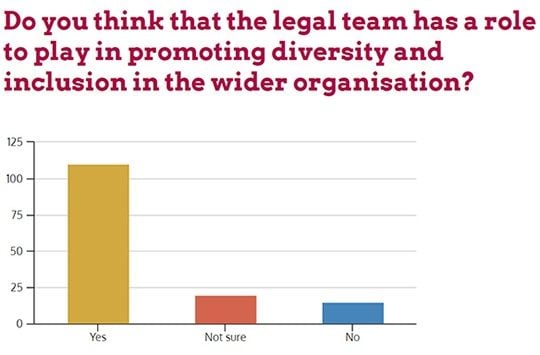

It has long been believed that in-house lawyers are professionals who have an unrivalled view of the company that they work within. Is it possible to combine their position, their extensive understanding of the law, in addition to knowledge of personal conduct to assist in developing an inclusive corporate environment? The vast majority of our survey participants believe that their legal team has a vital role to play in promoting diversity and inclusion. When asked to elaborate further, some thought that the legal department also has a guiding role in promoting diversity initiatives: ‘In the first instance, aside from HR, we are probably the department that best understands the subject legally so we’re in a great position to train and encourage understanding of this subject in others’.

Most of our respondents, however, felt that while legal has to contribute to diversity and inclusion actively, it does not have more of a role to play than other departments. Most of our survey participants responded negatively to the question ‘Are there specific initiatives that are unique to the legal department?’ This highlights the conviction of many professionals that while the legal department has to contribute to the diversity and inclusion vision of the company, these contributions should be within the framework of a broader corporate strategy.

Importance of diversity within law firms

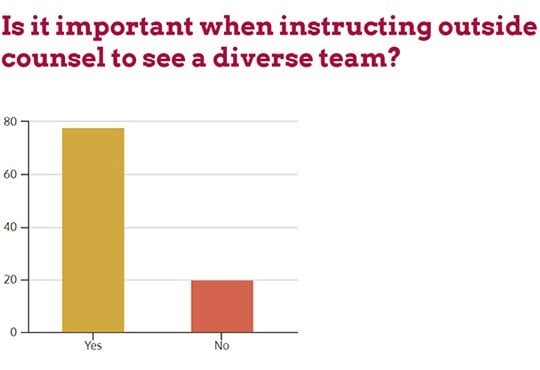

It is becoming increasingly common when instructing law firms for companies to demand the same level of diversity that they encourage within their own companies: approximately 61% of our respondents believe that it is important to see a diverse team when instructing outside counsel. When asked about reasons for looking for diversity in law firms some respondents explained that they saw value in the variety of opinion and creativity that diversity brings.

One respondent stated that ‘social and age diversity can bring different viewpoints and mitigate the risk of “group think”’, while another professional said that ‘creativity is fed by diversity – people thinking differently and coming at a problem from a different perspective sharpens everyone’. On the other hand, some respondents felt that client knowledge, experience and competence are more important areas of focus when assessing law firms, with some even suggesting that too much focus on diversity may be counter- productive. One respondent opined: ‘It would create an artificial environment rather than the merit one needs from external teams. Selection should be “diversity blind” otherwise it will skew matters. Positive discrimination is never a great idea in my opinion’.

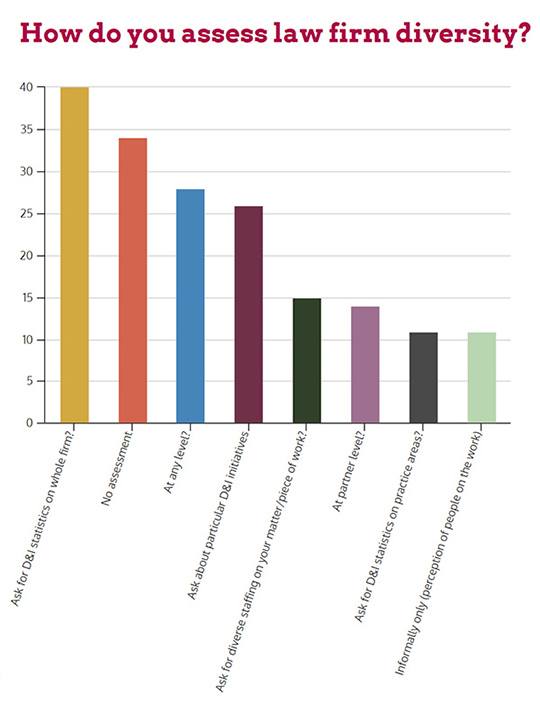

Finally, we asked our survey respondents to select the methods that they use to assess law firm diversity. The most commonly reported method was for clients to look for diversity and inclusion statistics of the whole firm, followed by inquiring about a particular diversity initiative. Less common methods were focusing on diversity and inclusion statistics on a specific practice area or specifically requesting diverse staffing on a particular matter or piece of work. Our respondents tended to focus primarily on diversity at any level rather than on partner level alone. Only 18% of our respondents did not assess law firm diversity.