Foreword

The way global companies handle data is set to change dramatically on 25 May 2018, when the European Union’s (EU) General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) comes into force. Designed to address concerns over the security and use of personal data, GDPR will apply to data processing activities regarding personal data within Europe as well as data transfers within the EU and between the EU and non-EU countries, and it looks likely to become the global benchmark for protecting personal data.

Legal teams are front and center as companies get ready to comply with GDPR, and the stakes are high. Companies that do not get compliance right risk fines of 4% of global turnover or €20m, whichever is greater. Regulators have made it clear that they intend to fully flex their powers to enforce the regulation.

Juerg Birri, Global Head of Legal Services

KPMG International

Compliance with GDPR aside, no business wants to face the reputational fall-out of failing to protect their customers’ personal information – as the WannaCry, Cambridge Analytica and far too many other breaches show.

How are legal teams working with businesses to prepare for the new regime, and are they confident they will be ready? KPMG International sponsored The Legal 500 to find out.

The results of a survey of 448 legal counsel and in-depth interviews with over 30 senior general counsels, set out in this report, combine to offer a view of the state of GDPR implementation worldwide. The countries, regions and jurisdictions covered in this survey – Australia, Brazil, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Russia, Spain, Taiwan, United Kingdom and United States – cover a range of key markets, both within and outside the EU.

The results of this survey reveal that legal teams face significant hurdles as they seek to implement a data protection management system that allows them to continue operations and capitalise on the valuable data they hold. Among the biggest challenges respondents faced:

-

- GDPR affects all parts of the organisation, which can frustrate efforts to determine responsibility and accountability. Implementing policies across the organisation was named as the top challenge by about one in five respondents.

-

- While the legal team is central to preparation efforts, success depends on its ability to work with other departments to map issues and develop solutions.

-

- The GDPR regime is based on principles rather than prescriptive rules, and interpretation of legal requirements and obligations can be difficult in the absence of precedents or additional guidance.

-

- GDPR compliance requires understanding and control over all of the IT systems and processes for handling personal data collection – including data that may be hidden in legacy architecture and systems.

-

- Few organisations have sought to understand the risks arising from the actions of third-party suppliers and other commercial partners; only 10% have made contact to check third-party compliance with GDPR.

- Finally, most organisations have struggled to identify all data processing activities or gain a broad internal overview of their processes. For GCs, this has made compliance a continually moving target.

Faced with challenges like these, only a minority of the legal counsel surveyed feel confident that their organisations have done enough to comply. Fewer than half (46%) of respondents believe their organisations are prepared for GDPR, while under 10% of respondents believe that employees at their organisation are fully aware of their data protection obligations under GDPR and national laws.

This report offers a view of how legal teams are addressing the challenges of GDPR and identifies a number of leading practices for getting organisations systems and processes onside. As legal counsel reported in interviews, the best solution to these challenges may be to focus on the opportunities. For example:

-

- Demonstrating GDPR compliance can be a good opportunity to differentiate your business by winning more consumer trust and thus competitive advantage.

- GDPR compliance can benefit the organisation’s culture, as stronger governance structures for handling data help mitigate other risks (e.g. security, bribery, corruption).

- More disciplined management of customer data can produce opportunities to build connections with customers and produce better products.

By approaching GDPR as a chance to invest in a leading-edge global data protection management system, KPMG member firm legal teams can help their clients get more control over data and leverage that data to gain more strategic value.

KPMG’s Global Legal Services practice is proud to support The Legal 500’s survey to better understand how organisations inside and outside the EU are preparing for GDPR as well as identify challenges they are facing along the way. The KPMG network of Legal Services firms are uniquely positioned to offer advice in this area due to our multi-disciplinary service approach, deep industry knowledge, and global reach. Our legal practices operate in 75 countries with over 1,650 legal professionals.

KPMG member firms may render legal services where authorized by law, with full observance of relevant local regulations. Legal services may not be offered to SEC registrant audit clients and/or affiliates or where otherwise prohibited by law.

The challenges of GDPR

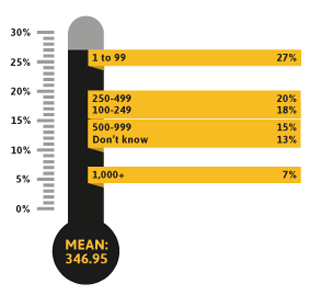

Our detailed survey took the views of legal counsel at 448 institutions globally, more than half (63%) of which had already appointed a dedicated data protection officer (DPO) or local representative in the EU. The median annual turnover of the organisations surveyed was $4.3bn.

The results of this survey, combined with in-depth, structured interviews with over 30 senior GCs globally, show the following issues are challenging legal teams when it comes to implementing GDPR.

Establishing who owns what

‘There are too many interested parties within the corporate ecosystem. This can lead to decision by committee. GDPR cuts across so many boundaries that it is difficult to know who is responsible. It’s all too easy to say “I’ve done my bit, it’s no longer my problem”, even though we know that is not the optimal solution from the organisation’s perspective’ (General counsel, TMT company).

Dealing with time and resource constraints

‘While the legal team is a key part of any GDPR strategy, ideally an organisation needs to appoint a ring-fenced team that is dedicated to compliance. This team should work with other departments to establish key areas of concern. Leaving it all to legal teams makes no sense in a business environment where the legal team already has a thousand other compliance challenges to meet’ (General counsel, TMT company).

Lack of support from the wider business

‘A lot of GCs are almost victimised by their organisations over this. If your IT teams won’t talk to you and show you the systems – either because they don’t see it as their job or they are not properly incentivised – then you can’t really do much’ (General counsel, consumer goods company).

Understanding GDPR itself

‘GDPR is not overly prescriptive about how to achieve compliance. It seems to allow for a degree of interpretation. While this is a positive, it does mean that organisations need to prioritise and decide on their policies. This feels like uncharted waters for me as GC. I am advising on something that I cannot control in reference to the law itself’ (General counsel, TMT company).

Maintaining a consistent approach globally

‘Ideally, a common language should be adopted and used to discuss compliance in all jurisdictions. That sounds very good in principle, but when you try to implement it in practice you realise it is all but impossible. We have too many staff to standardise our approach to compliance’ (General counsel, financial services company).

Understanding IT systems and processes underpinning data collection

‘We have spent a long time looking at data security and our handling of customer data and I have spent a long time on this personally. Like every GC, I have realised that the closer you look at it the more problems come out of the woodwork. Particularly when you dig into IT architecture and legacy IT systems. We are constantly finding stacks of data we’d forgotten about. We then need to address where it has come from and how it is being used’ (General counsel, consumer goods company).

Coping with ambiguity

‘GDPR has hit the IT community particularly hard and they have a very specific way of working that engenders itself to finding a right answer. As a compliance practitioner, I need to tell them it’s not always straightforward – there’s not always a right answer’ (Head of compliance, consumer goods company).

Assessing risks in the supply chain

‘The real difficulty with GDPR is working out which third-party relationships might get us into difficulty. Knowing how our commercial partners use data is a critical part of our compliance strategy but it is very difficult to monitor effectively. Even though we are not looking to monetise customer data it is absolutely crucial to be 100% on top of things’ (General counsel, TMT company).

Preparing for GDPR

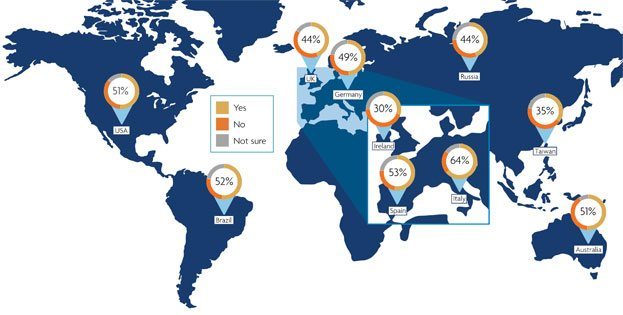

With just over a month to go before GDPR comes into force, fewer than half (46%) of respondents feel their organisations are sufficiently prepared.

Put another way, our survey shows that more than half of global businesses have failed to prepare for GDPR. Given the penalties organisations may face if they fail to comply by 25 May, this represents a significant source of regulatory risk in the market.

The good news is, it is not yet time to panic. GDPR compliance is a challenge for all organisations, but big steps toward meeting the regulation’s requirements can be made in a short space of time. In the following report, we hope to give a sense of how GCs are finding solutions to the problems of GDPR and how, by following their best-practice approach, others can address the challenges of GDPR compliance within their organisations.

Of all the challenges facing legal teams, establishing or adapting processes to ensure compliance is the most pressing.

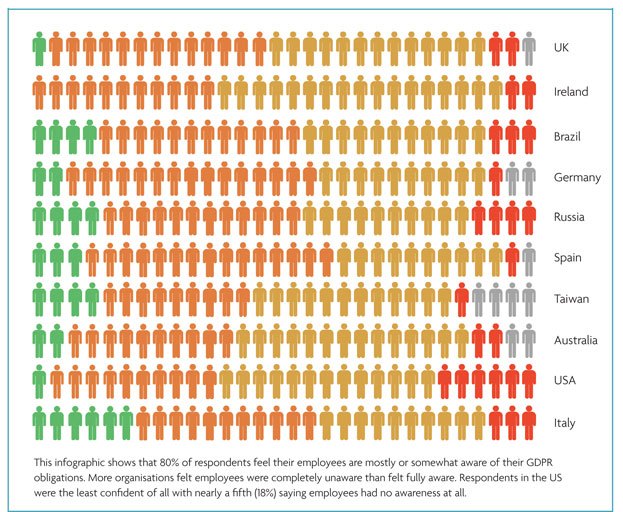

To what extent are employees at your organisation aware of their obligations under GDPR and applicable national laws?

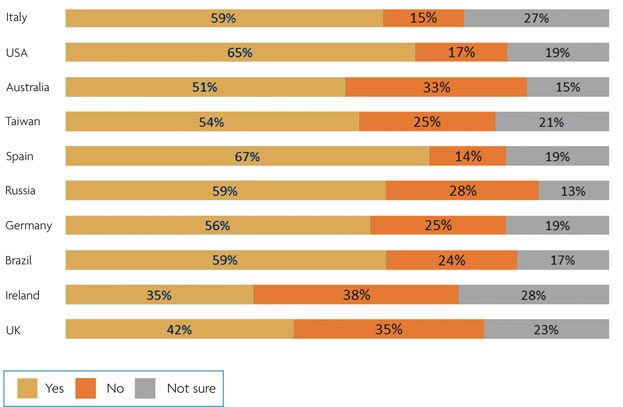

Over a fifth (21%) of respondents said implementing policies across all divisions of their organisation or group was the biggest challenge they faced. However, the perceived challenges varied greatly by country. Updating systems and changing the way in which the organisation stores data so that new rights such as the right to be forgotten can be implemented effectively was seen as the biggest challenge in the UK and Ireland, while ensuring ongoing compliance with GDPR was the top priority for businesses in Germany.

Transferring data to third parties, including those outside the EU, is also presenting a challenge. Just over half (51%) of organisations globally use EU standard clauses when transferring personal data to third parties, while less than a fifth (18%) are relying on adequacy decisions of the EU Commission.

Ensuring employees throughout an organisation are aware of how the new obligations apply to them is likely to cause problems long after 25 May.

While four fifths (80%) of respondents felt that employees were either somewhat aware or mostly aware of their responsibilities, it was notable that confidence fell off markedly at organisations with a group global annual turnover exceeding $1bn.

It was also clear that a significant number of organisations are likely to encounter serious problems related to employee awareness.

Fewer than 10% of respondents believe that employees at their organisation are fully aware of their obligations under GDPR and applicable national laws, while more GCs think the employees across their organisations are completely unaware of GDPR than think they are fully aware.

Do you think that your organisation is sufficiently prepared for GDPR?

Employees specifically responsible for processing personal data will be particularly important to an organisation’s compliance strategy. While more than half (55%) of respondents believed those handling and processing personal data understood the implications of GDPR, it was striking that nearly a quarter (24%) felt even these key employees were not aware of their responsibilities. Running due diligence on these employee groups is essential before 25 May.

Surprisingly, organisations based outside the EU reported low levels of preparation anxiety.

Respondents in Brazil expressed the most confidence (52%) that they would be fully prepared for GDPR, with similarly high confidence levels reported in Russia (44%), Australia (51%) and the US (51%).

It seems likely that these organisations may not be fully aware of what GDPR compliance entails.

Many respondents showed either a lack of familiarity with the regulation or a lack of concern over its extra-territorial scope. One Russia-based GC, representing a multinational organisation handling the data of EU citizens, stated: ‘We fall outside the scope of GDPR. Russia has its own data protection regime and is not in the EU, [as a result, GDPR] will not affect us.’

Such misplaced confidence may come at a high cost. A high proportion (72%) of these respondents represented organisations with subsidiaries or branches in the EU. Their organisations will certainly need to establish how personal data will be compliantly transferred between jurisdictions. Moreover, organisations not located within the EU but processing personal data of EU citizens must comply with GDPR, even if they only plan to use this data for the purposes of monitoring customer behaviour rather than direct marketing.

Within the EU, respondents in Italy were the most confident of all, with two thirds (64%) feeling their organisations are ready for GDPR – the highest of all countries surveyed globally.

However, fewer than half (49%) of Italian respondents had an overview of all data protection measures within their organisation, while just 38% said their organisations documented all data processing activities, the lowest rate among those surveyed. Complying with GDPR without such a record of activities will be difficult.

Our survey shows that, even for those organisations located within the EU, there is a high degree of misplaced confidence when it comes to assessing preparations for GDPR.

The politics of data

Following the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, data transfer is likely to become a key issue for GCs across a range of sectors. Ensuring that data continues to flow smoothly post-Brexit is a particular concern for financial services businesses. The UK government and the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) have offered encouragement that data adequacy decisions will suffice, but GCs are concerned that data flows may be disrupted in the months following Brexit. As one noted, ‘many of our EU-based counterparties have stated that adequacy decisions or other mechanisms for third-country transfers, such as model clauses, will not convince them to store data outside the EU.’ In short, whatever legal mechanisms are put in place by the UK, some counterparties will refuse to store data outside the EU. Further, there are questions over how the EU will treat the UK’s arrangements concerning data transfer to third countries such as the US.

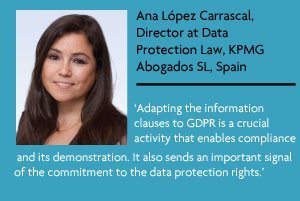

The views in brief

Kate Marshall, Partner, KPMG Law, Australia

‘KPMG professionals are still coming across organisations that have not understood which aspects of their business are subject to GDPR, and a large number of businesses that are required to comply haven’t realised it. All organisations should be aware that GDPR is likely to become the global benchmark for data privacy. Any organisation looking to expand its global reach or to build trust with customers should see steps toward GDPR compliance as a good thing.’

Andrew Yorston, Head of risk and compliance, Vodafone UK

‘We have taken a view that although GDPR doesn’t technically apply in some countries, we should have the same standards globally. A data breach problem in Egypt, for example, could cause just as many reputational headlines across the world as one in the UK or Spain. As an international company, we’re approaching this as an opportunity to raise standards across the board’.

Is data security and cyber risk considered a board-level issue in your organisation?

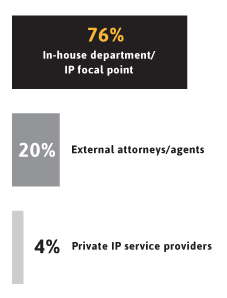

Who is responsible for GDPR?

GCs are taking ownership of GDPR. Across the organisations surveyed, GCs were responsible for setting data protection compliance policies in over a third (34%) of cases. Chief compliance officers took on the data protection burden in just a quarter (25%) of cases.

Whether or not an organisation’s GC is expected to manage GDPR compliance, legal teams will play a critical role in the process. Finding ways to work with different business functions, and to win organisational support for the project, will be essential to success.

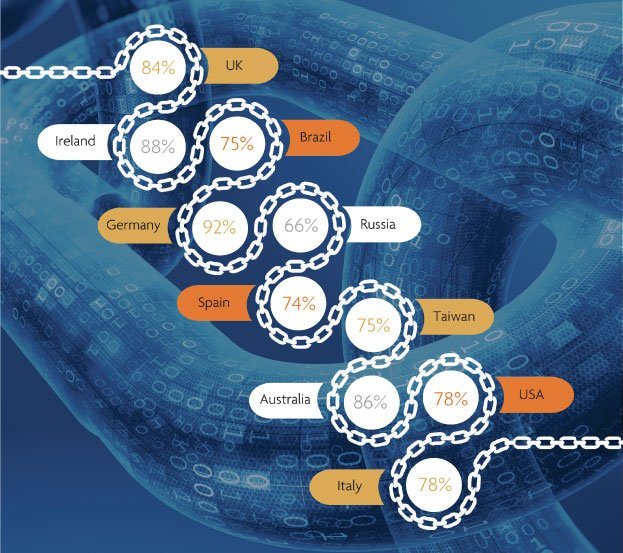

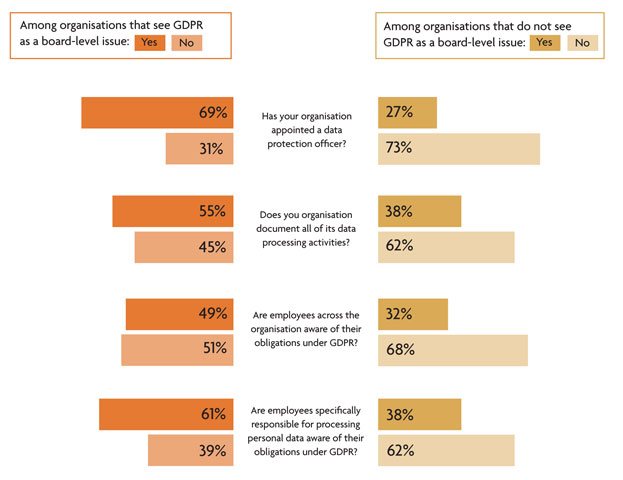

Our survey shows that organisations where data security and cyber risk is deemed a priority for the board tend to be further along their GDPR journey than those who do not.

‘Many of the tasks GCs will be expected to fulfil as data protection officers will be unfamiliar to them. Organisations need to help them understand their duties’

– Carolyn Jameson, General counsel, Skyscanner.

‘I spend quite a bit of my time as GC dealing with non-legal, organisational problems. There are mostly around communication failure, project management, change management and capturing knowledge. The real complexity hidden behind GDPR is not the law, it is the fact that so many different departments have to work together. As GC you need to connect all those people and capture the various different insights they have into the risks held by the business’

– Rachel Jacobs, General counsel, Springer Nature.

‘I sympathise with GCs who are finding it tough to get IT and other functions onside, but they need to make more of an issue of this at board level. As GC, you need to take control and push this at a senior level, even if you are not the named data protection officer’ – Alessandro Galtieri, legal director, corporate law and data protection, Colt Technology Services.

‘Being GC and also being responsible for data protection can create internal conflicts. It costs money, it makes things unsexy and complicated and if you comply with data protection law then your product becomes less attractive’

– Christian Unsinn, General counsel, Lemon Group Services.

Fully half (50%) of respondents who reported that their organisation saw these topics as a board-level issue also reported that they felt their business was sufficiently prepared for GDPR, compared to just 13% of those for whom data security and cyber risk were not board-level issues.

Making sure data security reaches the attention of senior management is the single most important thing GCs can do to prepare their organisations for GDPR. Our survey shows that an engaged board helps at every stage of the journey toward compliance.

The power of influence: How an engaged board can help drive GDPR compliance

Systems and processes

For GCs appointed to the role of data protection officer (DPO), getting an overview of the various data collection and processing systems across their organisation will be a challenge. This challenge is particularly pronounced at multinationals where staff operate in many different jurisdictions, each with its own data protection regulations.

‘Many of the elements of GDPR were already required in certain countries,’ says Jan Bredehoeft, head of legal for Germany at Huawei. ‘However, ensuring these elements are understood and complied with globally is a big challenge for a diverse, multicultural and data-heavy organisation. Data security and compliance processes are in place across various parts of the organisation, but putting them together to make sure there is a comprehensive control and follow-up strategy is a major piece of work.’

Establishing global data protection standards has, however, proved difficult for many. Just under half (47%) of organisations said data privacy was managed by a single, centralised function, while over half (55%) said they had put in place a single, global data protection standard.

Has your organisation adopted a data security compliance management system?

Further, as interviewees reported, ensuring on-the-ground compliance with these standards is a big challenge. Even for those based in countries with comparatively well-established data protection standards can struggle. ‘The main challenge is to implement structures across the whole group, including in markets where data protection law is not really common’, says Alexandra Albrecht-Baba, head of corporate compliance at Hochtief.

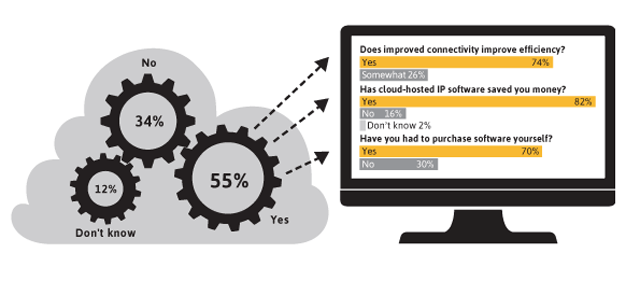

While software is being sold as a panacea for GDPR compliance, only 35% of businesses globally have implemented a software or IT-based GDPR compliance system.

Ireland-based organisations were the lowest adopters, with only 21% having introduced a software-based platform.

When it comes to monitoring compliance, most organisations are focusing on training staff in their use of email and IT systems. Just over half (51%) said they had developed internal policies for this purpose. However, as one GC pointed out, this is not exactly a surefire way to ensure compliance: ‘Knowing whether staff understand the risks surrounding use of data is the biggest challenge we face. You can send a circular message out about GDPR but you cannot police whether it will be read or followed.’

The views in brief

The risks

SUPPLY-CHAIN RISKS

Significant GDPR compliance risks can lie outside an organisation’s own staff or systems and processes. Any third parties to which an organisation transmits personal data must also be evaluated as part of its compliance strategy. While larger organisations will be able to access sophisticated compliance teams to help them implement GDPR, they will also face greater difficulties in addressing GDPR risk across their supply chains.

Just 10% of the 448 senior counsel polled for this report said that their organisation had contacted commercial suppliers and partners to check their compliance with GDPR.

Given the difficulties organisations will face in scrutinising global supply chains, many are looking to reduce the number of suppliers they work with. For example, one GC reported his team had helped shed over 50,000 suppliers in the past seven years. As an increasing number of companies begin to examine the compliance standards of their suppliers and review third-party contracts, it is likely that GDPR will cause a ripple effect that touches a far greater number of businesses.

Lawrence Ong, Partner,

KPMG Law Firm, Taiwan

For organisations based outside the EU, a mixture of political will and financial risk is likely to drive awareness. ‘Taiwan’s laws have historically been very close to the EU when it comes to data protection’, comments Lawrence Ong, a partner at KPMG Law Firm in Taiwan. ‘But while Taiwan had similar laws to the EU, it was never so serious when it came to fines. GDPR will change that and is helping to focus people’s minds.’

‘Taiwan is a very export-oriented economy and will do a lot to ensure its businesses are not at a competitive disadvantage’, Ong continues, ‘as such, there will be strong political support for GDPR compliance. However, for organisations themselves, the prospect of significant fines is much more likely to spur compliance.’

Adapting to the new laws will not be easy. ‘Data protection teams at Taiwanese organisations tend to be led by computer engineers rather than lawyers, but GDPR compliance is not a back-end, IT security issue. That means people need to adjust the way they think about privacy and take an approach that empowers legal teams to set strategy. Fortunately, a great many Taiwanese organisations are waking up to the fact that GDPR will apply to them and that a coherent compliance strategy will allow them to sell services to partners and customers much more effectively.’

HOW WILL THE REGULATORS RESPOND?

One small comfort for GCs has been the level of clarity offered by the regulations themselves. The work of The Article 29 working party was widely praised for achieving a workable approach to data protection by those we spoke to.

At the same time, a lack of certainty around how these will be enforced makes the precise level of risk difficult to judge.

Some believe that the regulators’ approach will be measured. As one Italy-based legal director commented, ‘data protection regulators are likely to make a distinction between those who have made sincere efforts to comply and those who have not.’

However, says Dr. Konstantin von Busekist of KPMG Law in Germany, there will be very little manoeuvrability on the part of regulators when assessing and imposing penalties for breaches. ‘The question of whether to prosecute is not at the discretion of the authorities. Whenever they have knowledge of an offence they have to prosecute. Even companies which fall outside high-risk sectors such as TMT and healthcare can be at risk from a strong works council, which may have a political interest in bringing the company before review.’

And, adds one GC with close connections to the regulatory authorities, ‘within six months of GDPR’s implementation the regulators will look to penalise a large corporate which has not complied. It’s certainly what I would advise them to do. If a year goes by without any large fines there is a risk that companies will become complacent.’

Andrew Yorston, head of risk and compliance at Vodafone UK has a similar take. ‘Our group audit and risk committee asked “what is the precise risk we face here?” It is hard to quantify the risk, but I advised them that, for GDPR to work as it should, there will have to be investigations. A single customer complaint will be enough to trigger an investigation’.

Digital citizens’ rights?

Dr. Konstantin von Busekist, Partner

KPMG Law, Germany

Under GDPR, companies must protect ‘any information relating to an identifiable person who can be directly or indirectly identified in particular by reference to an identifier.’ The protection of personal data is a laudable ambition, but it is frequently inconsistent with how individuals themselves share information.

‘The perception of data protection among our customers differs markedly from the perception of the regulators’ says Gianpaolo Alessandro, head of group legal, Unicredit. ‘Most people care very little about their rights when they use social networks or e-commerce providers. There seems to be an increasing gap between how regulators feel and how the people being regulated feel’, Dr. Konstantin von Busekist, KPMG Law in Germany adds.

‘We are moving toward a world where data collection becomes more invasive. The internet of things and other developments will make the question of what constitutes data privacy a difficult one’.

Conclusion

MAKING THE MOST OF GDPR

‘The problem with GDPR’, says Rob Green, data privacy director at Canon Europe, ‘is there are so many people with different opinions that you can run yourself into a circle of despair. GDPR clearly does represent a massive change, but GCs need to keep a cool head. A lot of this is not new at all.’

Gordon Wade of KPMG in Ireland offers similar advice. ‘There has always been and will always be a data protection compliance requirement. GDPR contains many of these existing principles and should be seen as an evolution rather than something to worry about.’

While the 25 May deadline does not leave GCs much time to work with, a lot can be done in a matter of days. Focusing on quick wins is the best approach for those who feel their planning is behind schedule.

Alexandra Albrecht-Baba, head of corporate compliance at Hochtief, puts it more bluntly. ‘There is a theoretical approach and a pragmatic approach [to compliance]. My impression is that all GCs are going to take the pragmatic approach until 25 May this year and only then try to consider what the best theoretical approach may be.’

Finally, as a number of GCs reported, the best solution to the challenge of GDPR is to make the most of it and focus on the opportunities it presents to an organisation.

GDPR IS AN OPPORTUNITY TO DIFFERENTIATE YOUR BUSINESS

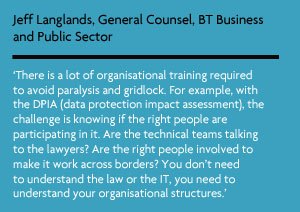

Jeff Langlands, general counsel, BT business and public sector

‘For a number of businesses, GDPR compliance can be a differentiator in the market. In the telecoms space that is definitely true. The money we spend on GDPR compliance is not a sunk cost, it is a way of getting an advantage on our competitors. There are also cultural benefits to GDPR compliance across the organisation. It stirs the pot and makes sure other risks – from security to modern slavery and anti-bribery and corruption – are placed under a better governance structure.’

Dan Guildford, general counsel, Financial Times

‘GDPR presents unique challenges for the media sector. Subscription-based media companies such as FT rely heavily on user data to help promote subscriber acquisition, retention and engagement, and GDPR also poses potential risks for journalistic freedom. We need to ensure that all of our lawyers have a good knowledge of data protection laws and are taking the lead on ensuring the company fulfils with its regulatory requirements under GDPR. Ultimately, if we get this right we will be well ahead of other organisations in our field.’

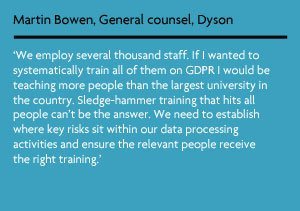

Martin Bowen, general counsel, Dyson

‘GDPR is often seen as a very onerous thing to comply with, but we see the opportunities. A future where we are connected to our consumers looks more and more likely. A rich seam of information will help us produce even better products if we can get the discipline of handling the data properly in place.’

Carolyn Jameson, group general counsel, Skyscanner

‘There is a big drive to personalise our product line, which will mean collecting more personal data. In this sense, GDPR has been fortuitous for the business and for me as DPO. It has given us an opportunity to think systematically about what we want to do with data before we collect it.’