Steve Jobs, the late co-founder, chairman and chief executive of Apple, once remarked that ‘innovation distinguishes between a leader and a follower’. This is a sentiment that could easily be applied to the modern legal market, where clients have been increasingly vocal in demanding a more imaginative approach to legal services and the most progressive law firms are trying to find new ways to stay ahead of the competition. Although we are unlikely ever to see the equivalent of the iPhone, there is plenty of room for a visionary law firm leader.

‘The need for greater operational efficiency is prompting many law firms to experiment with different ways of improving the efficiency of their business models. Some firms are reviewing their delivery models in quite fundamental ways, others are experimenting at the edges,’ says Neville Eisenberg, managing partner of Berwin Leighton Paisner, a firm that launched its own pioneering contract lawyer service, Lawyers On Demand (LOD), in 2007. ‘It is really important for the leaders of law firms to understand how clients’ views of service delivery are evolving and to develop clear thinking on what changes are required to the traditional law firm model to address this evolution. Law is a conservative profession, so real change requires decisive and courageous leadership which can inspire people to take the leap of faith required in order to work differently.’

Barriers to change

The biggest challenge progressive leaders in the industry wrestle with is a mindset and business model that is inherently conservative. Hourly billing targets and an obsession with profits per equity partner make it difficult to convince partners to invest in something that might not pay off for another three to five years.

This inherent problem with the business model was one of the first things Kevin Gold tackled when he became managing partner of Mishcon de Reya in 1997. This required a complete overhaul of how the firm financed itself and the changes that Gold ushered in – particularly management retaining a percentage of the profits to provide a capital base for expansion – required a large cultural shift, something that several senior partners reacted angrily to.

‘At the time, one or two partners disagreed with us, arguing the principle was to make as much money as soon as possible,’ says Gold. ‘As a result of that, and despite being big rainmakers, they left the firm. It was certainly a brave decision by our partners and the right decision in retrospect.’

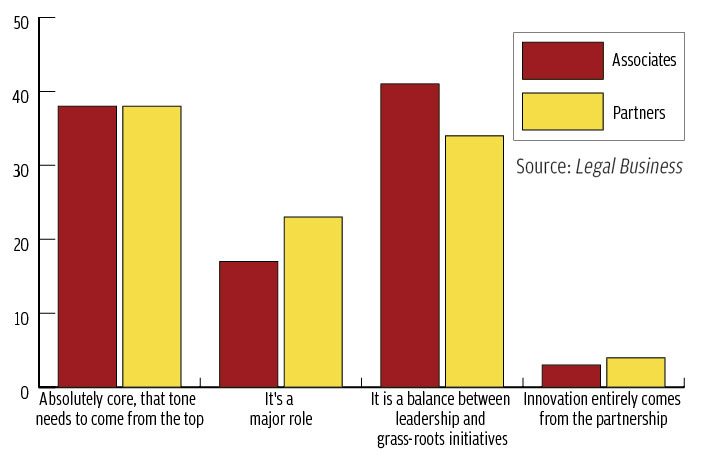

How important is central management at law firms to pushing forward innovation and improvements in service delivery?

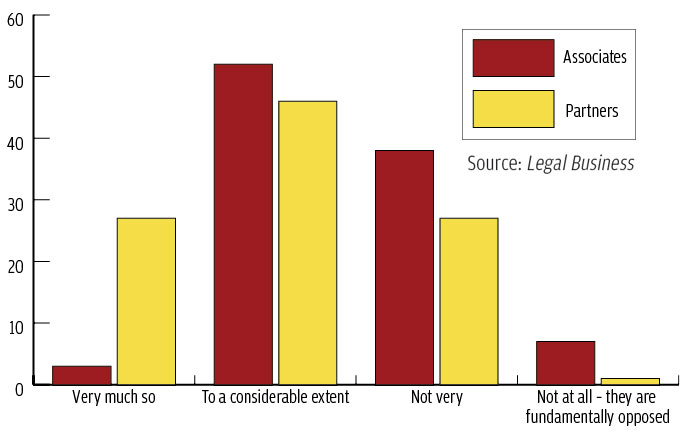

How compatible is a partnership with a culture of innovation and searching for improving service delivery?

But if there are generational tensions, it isn’t just from the more senior partners. Often, it is the younger end of the spectrum that needs to be more carefully handled. Eisenberg notes that the new generation of lawyers coming in has a different approach, far less focused on building a long-term career at the firm and more likely to move between law firms and even clients. ‘Their approach to career planning is more short term,’ he says. ‘It’s a completely different perspective. Understanding that is very important.’

This issue could have huge long-term relevance for the stability of law firms and how they tackle their succession planning, not just from one leader to the next, but one generation to the next.

‘Senior leaders often say that the younger partners have less of an expectation of autonomy and involvement in leadership issues, which on the one hand makes the life of the senior partner a bit easier, but actually it can also be a real frustration and a hindrance,’ argues Professor Laura Empson, director of the Centre for Professional Service Firms at Cass Business School. ‘The reason partners get agitated and difficult about things is that they have a really strong sense of ownership of the organisation, and if you’ve got a bunch of young partners who feel disconnected and very much focused on what they need to do to maximise their billable hours and keep their clients happy, that can be a problem when you look to the next generation of leaders and you realise, well, there aren’t any.’

‘A busted business model’ – the client view on law firm innovation

Andrew Garard, group legal director and company secretary at ITV, is forthright when discussing where law firm leaders are going wrong. For Garard, these failings came sharply into focus not long after Lehman Brothers collapsed, when he attended a discussion between senior lawyers about how they were responding to the downturn.

‘For the first hour in that room, I didn’t hear the word “client” mentioned once,’ says Garard. ‘Then the moderator turned to me, and I said: “I’m shocked that I’ve sat here and that nobody has thought about the cash-generating part of the business, ie the client, because if you don’t have clients you don’t have a business. All of this has been about how you are going to structure your business and you may not have a business after the recession.”’

Garard is not alone in his views and in-house lawyers will readily fling accusations of complacency at private practice. Another part of the problem is, as one GC puts it: ‘A busted business model that they don’t yet fully realise is busted.’

Many GCs believe that the traditional law firm model is a particular block to adaptation because innovation often requires investment and law firms tend to distribute nearly all their profits every year, which doesn’t leave much capital to invest.

One FTSE 100 GC, however, believes quality leadership helps certain practices stand out and if the law firm leaders demonstrate an appetite for innovation, the partners and lawyers will follow their lead. ‘For me the most innovative firms tend to be the ones with fantastic leadership – leaders who have a really good view of how the world is going to be and what it needs, and they just share that and stamp it on the partnership,’ they say.

If the typical law firm-client relationship needs improvement, most GCs admit that the fault doesn’t lie solely with their advisers. A law firm can only remain complacent if their clients are equally recalcitrant. Another FTSE 100 GC admitted instructing one firm purely through force of habit, even though the service was below par.

Indeed, most neutral observers with a solid knowledge of the legal industry would conclude that time-pressed in-house teams are generally much better at talking up innovation than themselves implementing the processes to support it. In-house teams are also generally much worse than private practice at sharing good ideas or innovation.

The manner in which buyers of legal services gauge value also needs addressing.

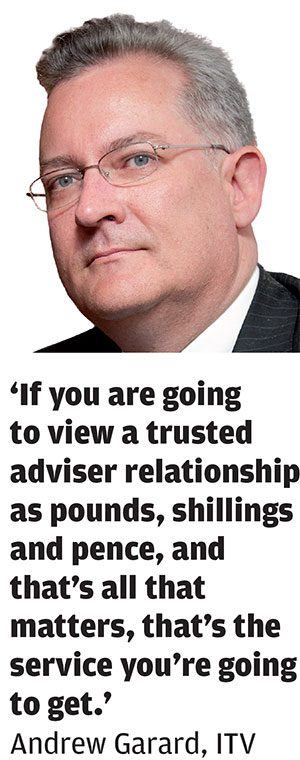

‘Unfortunately the procurement industry has infected a lot of corporates,’ says Garard. ‘The great thing about procurement teams is that they understand the cost of everything, but the value of nothing. If you are going to view a trusted adviser relationship as pounds, shillings and pence, and that’s all that matters, funnily enough that’s the service you’re going to get.’

Law firm leaders in turn are faced with the fact that, no matter how hard they try, there can never be a one-size-fits-all widget that will keep the entire market happy.

‘There isn’t a lot of uniformity as to what clients want,’ says Jonathan Watmough, managing partner of RPC. ‘Some want fixed fees – which we prefer – while others still focus on the hourly rate.’

The firms that have an edge are, therefore, those that offer the client a spread of options. To do that requires a law firm culture that rewards fresh thinking as much as it does hours billed and the managing partner must spearhead this.

From the client’s perspective, this doesn’t just revolve around pricing, other issues such as diversity and pro bono are also increasingly important, as is the need for an understandable service that speaks the business’s language.

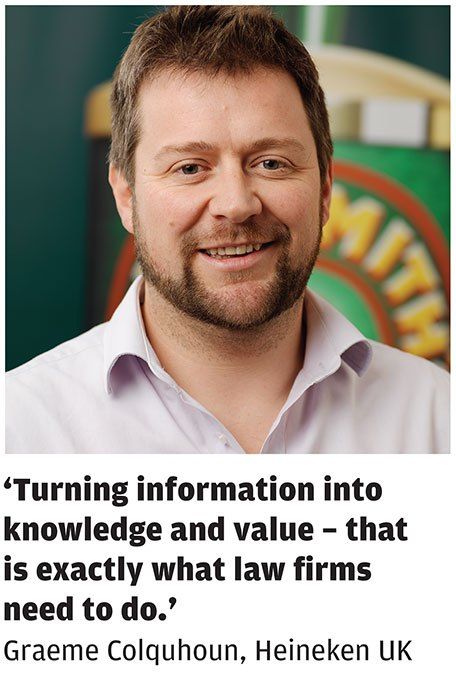

‘Some of the law firms think it’s “how good are my lawyers?”,’ says Graeme Colquhoun, head of UK legal at Heineken. ‘What I want is a quarterly report that gives me management information in a way that the business understands it. Law firms are good at providing legal advice, but they aren’t good at providing GCs with the information that can be used for the business. Turning information into knowledge and value – that is exactly what law firms need to do.’

While there is plenty of room for improvement, most GCs acknowledge that the best firms are catching on, albeit at their own steady pace.

‘It’s an inherently conservative market so the scope for massive innovation is limited, but it is incremental,’ says BG Group’s GC, Graham Vinter. ‘Go back 20 years and these firms have come a long way. If you are working as a GC in a FTSE 100 company, you’re absolutely spoiled for choice. The strength of the legal market is unbelievable, so although we might be carping around the edges, the general message is that we’re pretty well served and we’ve got a lot of choice.’

That surplus of choice might be good news for GCs, but for law firm leaders it still means selling your product in an increasingly demanding market.

Bottom up innovation

One of the best ways to tackle the problem is by empowering the younger generation of lawyers. This can come through the use of formal organisations such as Latham & Watkins’ influential associate committee (something that outgoing chairman and managing partner Robert Dell led before taking charge of the trail-blazing US law firm as a whole), or through fostering a culture of innovation that comes from the ground up.

The responsibility for nurturing that culture of innovation ultimately falls upon the leader. ‘You can only develop that culture from the top by showing how much you value innovation,’ says Dell. ‘If any lawyer is willing to spend the time on innovation, we’re certainly willing to support it. We tell our lawyers this is valuable recorded time and it’s going to be highly valued.’

Setting up a research and development budget is one way of addressing this, and Allen & Overy (A&O) has its innovation panel, chaired by energy and infrastructure partner Jonathan Brayne, which makes awards to staff that come up with new ideas.

Once that culture of innovation has been established, it can also become a self-perpetuating cycle, where the experimentation breeds further innovation. This is something that David Morley, senior partner at A&O, believes has been the case following the success of its legal and support services centre in Belfast – opened in 2011 and now housing some 400 staff – which has directly led to new initiatives such as Peerpoint, its contract lawyer business launched last year.

‘Because we’re able to point to Belfast, which everybody acknowledges has been hugely successful and beneficial, that gives us a lot of political capital to try other things like Peerpoint,’ comments Morley. ‘The thing with innovation is that you never quite know whether it’s going to work or not. By definition it hasn’t been done before, so we’re taking this seed capital approach to some carefully selected new ideas and trying them out.’

Leadership lessons: Neville Eisenberg, Berwin Leighton Paisner

‘A mere babe in arms’ is how Neville Eisenberg describes his 37-year-old self when he became managing partner of legacy law firm, Berwin Leighton, in 1999.

At the time, Eisenberg became a target for the legal press, which ran mocking cartoons featuring babies in nappies. But despite the fact he had only been a partner for three years, the firm saw something in Eisenberg that his detractors had missed. He was already a board member and, after leading a lengthy strategic review, became a candidate for the top job.

The partnership had the foresight to see that Eisenberg possessed one of the prerequisites for any law firm leader seeking to initiate long-term strategic change: youth, something that is often counterintuitive to a profession built around post-qualification experience. But the fact that he was learning on the job meant that he also needed time to hit his stride. The new role took a while to get used to.

‘It was a big shock to the system,’ he recalls. ‘Management is very different from client work. Client work is project based: you have a beginning and an end to the assignment, and you usually have a reasonable sense through feedback of whether you did a good job or not, whereas with management there is no start, there is no end and the feedback that one gets is only very occasionally relevant.’

Fifteen years on and almost five terms in, one would assume that Berwin Leighton Paisner (BLP) partners are satisfied with the job he has done. For Eisenberg, the biggest achievement to date was the merger between Berwin Leighton and Paisner & Co in 2001, which ‘was fundamental because it created a platform of sufficient scale for the firm to then go on and achieve a number of things’. The merger created a 122-partner firm that has now grown, more or less organically, to 213 partners. Since 2006, the firm has also expanded its London-centric strategy to include offices throughout Europe, the Middle East and Asia. The firm also helped to shape the legal market with its successful and much-copied 2007 launch of Lawyers On Demand (LOD), which provides teams of freelance lawyers to in-house legal departments and other law firms.

In pushing through recent changes, Eisenberg applied the same consensual and data-driven approach that he used for the original 1999 strategic review that caught the partnership’s eye in the first place.

‘You need to get people engaged in a change process and you can only do that by giving them the opportunity to understand the reasons for change, become involved in developing the solutions and become engaged with whether the solutions work from a client perspective or not,’ says Eisenberg. ‘In my experience, if people have had the opportunity to be involved and there is a good business case, and there is sufficient data supporting the proposals, then people will follow determined leadership in the direction they are trying to move.’

There have been challenges as well as well as plaudits. After a decade as one of the UK’s most upwardly mobile major law firms, BLP faced a torrid 2012/13 when it was caught out by over-expansion, some poor lateral hires and intense pricing pressure from rivals, leading to a sharp fall in profits and fees. However, the firm rebounded with a notable upturn in the 2013/14 and this summer moved to regain its innovative edge with the announcement of a new low-cost centre in Manchester, which is to combine with the expanded service line from LOD as the latter business continues to move beyond its original secondment business into fully-fledged project management via its OnCall service. The Integrated Client Service Model, which will include pro-actively mapping out and, if necessary, breaking up work flows – has been touted as the most imaginative and far reaching project BLP has yet attempted.

Convince early, execute fast

One common complaint is that even when a law firm does hit upon a potent idea or strategy, the partnership model, with its emphasis on consensus, will often slow down the process to such an extent that initiatives can stall indefinitely. That the process can be cumbersome is undeniable, but successful leaders agree the key issue is to front-load the decision-making and debate with the partners (see ‘Visionaries, politicians and survivors’), then once the decision has been made, the implementation can be swift.

It is also worth noting that for all the criticism about partnership as a bar to change, research conducted by Legal Business demonstrates substantial confidence in the need for leaders to push law firms to change.

The research for this report, which included responses from over 300 partners, found that well over half of partners thought that central management was either ‘absolutely core’ or had a ‘major role’, while less than 5% thought the C-suite played a secondary role to the partnership on the ground.

Likewise, partners were confident of the ability to combine partnership and innovation, though associates were considerably more ambivalent on the point.

For the leaders that we spoke to, the problem is less about partnership and more to do with a loss of direction and culture.

‘It’s got nothing to do with the business medium of partnership, it has everything to do with a lot of law firms having junked their partnership cultures,’ argues Jonathan Watmough, managing partner of RPC. ‘You can have a partnership culture but be a corporate; the two are not mutually exclusive – Goldman Sachs is an example: it has a partnership culture, but it’s listed. Equally, you can have a partnership with no partnership culture and a lot of law firms are in that bind at the moment. It’s partly as a result of neglect and partly as a result of the boom period of the mid 2000s – in the pursuit of growth and PEP, they lost touch of their values and what got them there in the first place. And once that culture has gone, it’s gone.’

Nevertheless, the shift towards alternative models, such as LOD or Peerpoint, is inevitable according to our law firm leaders. Law firms moving out of this grey area and embracing a completely alternative business structure seems unlikely at this point, particularly when it comes to high-end legal services. However, many leaders retain a scepticism towards taking a radical approach to structure, but don’t deny the obvious business case behind a law firm receiving outside investment, something that would be potent for funding future innovation and growth. Whether corporate financiers would want to make that investment into certain partnerships is another matter entirely.

‘At a firm like Mishcon it is difficult because the people that drive the business are highly individual: your best people are your biggest mavericks in a strange way. Corporates can’t deal with that very easily,’ concludes Gold.

Such a dynamic suggests law firms may be likely to pursue means of securing capital to invest that doesn’t involve selling equity stakes, either through retaining profits or more imaginative debt financing.

Ultimately, it is that maverick spirit, and the individualism and autonomy, that partners enjoy, which must be harnessed by the law firm leaders themselves. ‘Those are the people who are going to be innovating, pushing for change and are really going to be anticipating clients’ needs,’ says Empson. ‘Those are the people who push an organisation forward. The role for the leadership is to encourage them to make things happen.’

For the full Insight report, please see: ‘The partnership dilemma’ in Legal Business.