Introduction

In recent years, China has become an increasingly important jurisdiction for pharmaceutical patent protection, including patents covering the medical use of known substances. However, enforcement of medical-use patents in China presents unique legal challenges stemming from statutory exclusions and limited judicial practices. This article provides an in-depth analysis of the Chinese legal framework governing medical-use patents, practical insights drawn from judicial decisions, and important considerations for pharmaceutical companies seeking to protect and enforce their medical-use patent rights in China.

- Background and Legal Context of Medical-Use Patents

In many jurisdictions, including Europe, China, and Japan, methods of medical treatment on humans are explicitly excluded from patent protection for ethical and practical considerations. Such methods act on living human bodies with inherent individual variabilities, limiting their applicability and industrial utility; and, more importantly, public policy favors ensuring unrestricted access to medical care and preserving the freedom of medical practice.

International agreements, including the TRIPS Agreement, the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), and the European Patent Convention (EPC), consistently uphold this exclusion. However, an important exception emerged in Europe through Article 54(5) of the EPC 1973[1], which permits patents on the first medical use of a known substance, expressed as: “Substance X for use in the treatment of disease Y.”[2].

To address subsequent medical-use innovations, the Swiss Federal Intellectual Property Office introduced the Swiss-type claim format in 1984: “Use of compound X in the manufacture of a medicament for the treatment of condition Y.”[3] This approach enabled second medical uses to be patentable as industrial manufacturing processes. The European Patent Office’s Enlarged Board of Appeal endorsed this mechanism in the landmark 1984 EISAI/Second Medical Indication decision.

- Medical-Use Patents in China

- Swiss-Type Claims: Drafting Medical-Use Claims

Consistent with international norms, Article 25 of China’s Patent Law excludes methods for diagnosing or treating diseases from patent eligibility[4]. When China’s first Patent Law was enacted in 1984, it initially prohibited patenting pharmaceutical products and chemical substances entirely[5]. This changed in 1992, when China amended its law to allow pharmaceutical substances to be patented[6].

A key milestone came with China’s first Patent Examination Guidelines in 1993, which officially recognized Swiss-type claims as allowable for medical-use patents. Such claims are typically drafted as: “The use of compound X in the preparation of a drug for treating disease Y.”[7] Swiss-type claims have since become the standard legal mechanism for protecting medical-use inventions in China.

- Patent Application Statistics

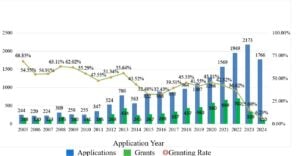

To gain insight into China’s medical patent practices, we analyzed medical-use patents using a third-party database compiled from publicly available information on patent applications filed in China[8][9][10]. Data from 1993 to 2024 reveals several notable trends in China’s medical-use patent landscape:

- Limited Valid Patents

From January 1, 1993, to December 24, 2024, a total of 17,901 medical-use patent applications were filed. Among these, only 4,865 patents are currently valid, while 8,212 have been declared invalid, and 4,824 are still under examination.

- Rapid Growth since 2005

There has been a marked increase in medical-use patent filings since 2005, with a particularly sharp rise from 2020 onward. For instance, while only 244 applications were filed in 2005, the number jumped to 2,173 in 2023. Additionally, data from the CNKI literature database indicates increased academic discussion surrounding medical-use patents, underscoring their rising importance alongside global pharmaceutical market expansion.

- Declining Grant Rates

The granting rate for medical-use patents has declined in recent years compared to the early 2000s. While the exact cause remains uncertain, some third-party analyses suggest that the decline may be attributable to heightened scrutiny regarding claim novelty and stricter patent examination standards[11]. A summary of the granting rate trends is illustrated in the figure below.

- Efficient Examination Timelines

Over the past five years[12], the average time required for the granting of medical-use patents has ranged from one to three years. In 2023, most patents granted were originally filed in either 2022 (389 patents) or 2019 (276 patents), indicating a generally efficient examination process for this type of claim.

- Common Technical Features

Data from the third-party database reveals that medical-use claims typically fall into three key technical categories[13]:

1) Therapeutic Target – e.g., specific diseases such as tumors or childhood leukemia;

2) Route of Administration – e.g., oral, intravenous, or intramuscular delivery;

3) Administration Method – e.g., dosage per use, frequency of administration.

- Additional Observation from CNIPA Data – Small Proportion of Medical-Use Patents in the Pharmaceutical Sector

Additionally, according to the Statistical Monitoring Report released by the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) in July 2024[14], approximately 36,000 patents were granted in the pharmaceutical and medical fields from 2018 to 2022. Of these, only 2,183 were Swiss-type patents, accounting for roughly 6% of the total—confirming that Swiss-type claims remain a relatively small but significant subset of pharmaceutical patents.

- Number of Medical-use Patent Applications[15]

- Enforcement Insights: Legal and Practical Considerations

Moreover, based on publicly available case information, we identified seven medical-use patent infringement cases adjudicated by Chinese courts. Key details of these cases are summarized in the Appendix. The analysis of these cases provides valuable insights into the enforcement landscape for medical-use patents in China.

- Favorable Outcome Where Patent Validity Upheld

Out of the seven cases reviewed, courts ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in four cases, while the remaining three cases were dismissed. In the successful cases, the courts found that the labels of the accused drugs disclosed the patented medical indications, thus supporting the infringement claims. In contrast, the dismissed cases were primarily due to the invalidity of the asserted patents.

- Modest Damages Awards

In the four cases where infringement was established, the average statutory damages awarded were approximately RMB 262,500. The relatively low damage amounts stemmed from limited evidence regarding the defendants’ profits or the plaintiffs’ actual losses. As a result, the courts applied statutory damages, reflecting the generally low sales volumes of the infringing products.

- Experienced Courts Handling These Disputes

Of the seven cases:

- Two were reviewed by the Supreme People’s Court (second instance) and Shanghai Intellectual Property Court (first instance)

- One was heard by the Beijing High Court (second instance) and Beijing Second Intermediate Court, and

- Four were adjudicated by the Nanning Intermediate Court, Beijing Intellectual Property Court and Shanghai IP Court (first instance).

All these cases were handled by specialised IP courts or courts experienced in adjudicating patent cases.

- Product Labeling as Key Infringement Evidence

Patent infringement analysis in China applies the comprehensive coverage principle, which requires that the allegedly infringing product or method correspond to each and every technical feature of the asserted patent claim. If even one essential element is missing, the claim of infringement cannot be sustained.

In the context of medical-use patents, this principle places particular emphasis on the product labeling of the accused drug. Courts carefully examine whether the label—explicitly or implicitly—discloses all elements of the asserted claim, especially the indicated therapeutic use. If the court finds that the labeling aligns with the patented indication, it will likely rule in favor of the patentee.

A clear example of this can be seen in the two related cases: Huana v. Company S and Dalian Zhongxin (respectively referred to as “No.1156 Case” and “No. 1158 Case”), which involved same parties and product but different patents. The asserted claims were as follows:

- Claim 1 in No. 1158 Case: “Use of L-ornidazole in the preparation of drugs against parasitic infections”; and

- Claim 1 in No. 1156 Case: “Use of L-ornidazole in the preparation of drugs against anaerobic bacterial infections.”

The label of the accused drug stated: “Indication: According to the clinical trial data, L-ornidazole is used to treat infectious diseases caused by sensitive anaerobic bacteria and trichomonas urogenital tract infection.”

The Supreme People’s Court held that this indication fell within the scope of both asserted patents, as it covered both parasitic and anaerobic bacterial infections, thereby meeting the required mapping under the comprehensive coverage principle. Consequently, the court found that the accused product infringed the medical-use patents.

Similarly, in the case of Wuhan Conform Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. v. Company Y Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Company Y Group Co., Ltd., the asserted patent’s Claim 1 stated:

“Use of a β-blocker in the preparation of a drug for the treatment of capillary infantile hemangioma, wherein the β-blocker is naphthol or its medicinal salts.”

The label of the accused drug described its indication as:

“The main component is propranolol hydrochloride, …for the treatment of proliferative infantile hemangioma requiring systemic treatment.”

The propranolol hydrochloride is medicinal salt of naphthol, which belongs to B-blocker.

The Beijing IP Court held that this indication aligned with the patented use. As such, the therapeutic use disclosed in the label was found to fall within the scope of the asserted claim, thereby supporting a finding of infringement.

In addition to product labels, advertising and promotional materials—such as product brochures—may also serve as critical evidence in infringement cases involving medical-use patents. This was evident in Nanning Yongjiang Pharmaceutical v. Wuhan Tongshi Pharmaceutical and Yichang Sanxia Pharmaceutical.

In that case, the asserted patent claimed:

“Application of L-lysine hydrochloride in the preparation of drugs for the treatment of craniocerebral injury.”

The label of the accused drug indicated that it could be used as an “adjunct therapy for encephalopathy.” Furthermore, the product brochure, published on the website of the defendant Wuhan Tongyuan, explicitly stated that the drug could be used for craniocerebral trauma and its associated syndromes.

The Nanning Intermediate Court found that craniocerebral injury is a form of encephalopathy, and that the brochure made direct reference to the patented indication. Based on this evidence, the court concluded that the accused product infringed the asserted medical-use patent.

- Joint Liability of Manufacturers and Sellers

In these decisions, courts consistently imposed joint liability on both manufacturers and distributors involved in commercializing infringing drugs.

For instance, in Huana v. Company S and Dalian Zhongxin, the defendant Company S was responsible for manufacturing the accused drugs, while both defendants were involved in selling and offering the products for sale. The Supreme Court found that all parties were jointly liable for patent infringement due to their respective roles in the commercialization of the infringing products.

Similarly, in Wuhan Conform Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. v. Company Y Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Company Y Group Co., Ltd., although the plaintiff could not prove that the accused drugs were manufactured by the defendants, the Beijing IP Court found that the defendant Company Y Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. had listed the drugs on a government procurement platform. The court held that this conduct constituted an offer for sale, which is sufficient to establish infringement under Chinese patent law.

In Nanning Yongjiang Pharmaceutical v. Wuhan Tongshi Pharmaceutical and Yichang Sanxia Pharmaceutical, the court found that Yichang Sanxia Pharmaceutical manufactured the infringing drug, while Wuhan Tongshi Pharmaceutical and Shenzhou Pharmaceutical Company were responsible for distributing it. Based on these facts, the Nanning Intermediate Court ruled that all three defendants were liable for direct and joint patent infringement.

- Injunctive Relief Available

Under Chinese law, a plaintiff may request a permanent injunction to halt ongoing patent infringement. In cases involving process patents, the court may order the defendant to cease using the patented process, as well as to stop using, offering for sale, selling or importing any product directly obtained from that process.

In these medical-use patent cases where infringement was found, courts ordered manufacturers and sellers to cease manufacturing, offering for sale, and selling the infringing drugs. Additionally, courts ordered the destruction of infringing inventory.

For example, in the two cases of Huana v. Company S and Dalian Zhongxin, the Supreme People’s Court ordered the defendants to stop manufacturing, offering for sale, and selling the infringing drugs. Moreover, the Court ordered the destruction of 300 infringing products, which were proven to be part of the defendants’ inventory.

In Wuhan Conform Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. v. Company Y Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Company Y Group Co., Ltd., the infringing act consisted of listing the infringing drug on a government-run pharmaceutical procurement platform. The court ruled that this act constituted an infringing “offer for sale” and ordered the defendant Company Y Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. to delist the product from the platform.

In certain cases where the label of the accused drug includes both infringing and non-infringing indications, courts may opt for a more tailored remedy. In Nanning Yongjiang Pharmaceutical v. Wuhan Tongshi Pharmaceutical and Yichang Sanxia Pharmaceutical, the court held that since the accused drug could be lawfully used for other indications not covered by the asserted patent, the defendants were ordered to remove the patented indication from all product labels and promotional materials.

- Damages Calculation

Under Chinese patent law, the calculation of damages in an infringement case follows a tiered framework:

1) Actual loss suffered by the patentee or

2) Illegal gains obtained by the infringer, or

3) Reasonable royalties, if the first two cannot be established, or

4) Statutory damages, if none of the above are ascertainable.

In cases of willful infringement under serious circumstances, courts may apply punitive damages, which can be one to five times the base amount of damages. However, punitive damages do not apply in cases where statutory damages are awarded in lieu of actual or estimated losses. Statutory damages in China range from RMB 30,000 to RMB 5 million.

In practice, an infringer’s illegal gains are typically calculated by multiplying the number of infringing products sold by the profit per unit. This is usually based on the infringer’s operating profit. If the infringer’s business is primarily centered around the infringing activity, sales profit may be used instead.

Plaintiffs typically present a variety of financial and commercial documents to substantiate claims regarding the revenue and profits derived from the infringing products. These may include financial reports, sales contracts, government procurement announcements, and invoices.

For instance, in the case of EIKEN v. DEAOU[16], the plaintiff submitted government procurement records to demonstrate the revenue generated by the allegedly infringing detection kits. Additionally, the plaintiff introduced industry financial reports from comparable companies to establish a reasonable profit margin attributable to the products. The Supreme People’s Court accepted this evidence and ultimately awarded RMB 2,247,547.24 in damages, calculated based on the defendant’s illegal gains from the infringement.

In medical-use patent infringement cases, the scope of damages may depend on the overlap between the product label and the asserted patent claims:

- If all labeled indications of the accused product fall within the scope of the asserted patent, damages may be calculated based on the total profit from sales of the infringing product to all patients.

- If the product label includes both infringing and non-infringing indications, damages may be apportioned based on the estimated profit attributable to sales for the patented indication only.

Nonetheless, in the medical-use patent cases we surveyed, plaintiffs failed to provide sufficient evidence of actual losses or the defendants’ unlawful gains. As a result, courts defaulted to awarding statutory damages instead.

In the two cases—Huana v. Company S and Dalian Zhongxin, the plaintiff did not submit any evidence regarding the actual losses suffered due to the infringement or the profits gained by the defendants. It only showed that the accused drugs were launched in four big cities and submitted a new on a defendant’s website providing that “…The company has planned and constructed a dedicated production line for 30-ton levornidazole raw materials and a tablet production line with an annual output of 100 million tablets…”.

The Supreme Court held that, since the plaintiff failed to provide evidence of actual losses resulting from the infringement or profits gained by the defendants, statutory damages should be applied. In determining the amount of statutory damages, the courts took into account the specific circumstances of each case, including the type of patent asserted and the nature and context of the defendants’ infringing acts. Ultimately, the courts awarded statutory damages of RMB 300,000 in each case, without providing a detailed analysis or explanation of the calculation.

In Wuhan Conform Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. v. Company Y Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Company Y Group Co., Ltd., the plaintiff only provided evidence that the accused products were listed on some government medical insurance procurement and that the defendant had offered the drugs for sale. Since the plaintiff did not show either its actual loss or the defendants’ profits, the Beijing IP Court awarded statutory damages of RMB 50,000, noting that the defendants’ infringing activity was limited to offering the drugs for sale.

In Nanning Yongjiang Pharmaceutical v. Wuhan Tongshi Pharmaceutical and Yichang Sanxia Pharmaceutical, the plaintiff presented limited evidence showing that the accused products had been launched in certain cities. However, the plaintiff failed to show the actual losses suffered or the profits earned by the defendants. The Nanning Intermediate Court stated that it conducted a comprehensive assessment of factors including the defendants’ level of fault, the duration of infringement, production volumes, and the scope of the sales market. Based on this assessment, the court awarded statutory damages of RMB 400,000, though it did not provide a detailed breakdown or reasoning for the damages amount.

- Absence of Indirect Infringement Precedents

Under Chinese law, defendants in patent infringement cases may be held liable for indirect infringement, which includes both contributory infringement and induced infringement. This implies that drug manufacturers or sellers could face liability if they knowingly assist healthcare professionals or independent clinical laboratories (ICLs) in practicing a medical use patent.

The meet the requirement of indirect infringement, one must 1) have intention to induce or incite others to infringe upon the patent rights, and 2) actually provides the necessary conditions to facilitate others’ direct infringement.

To date, there have been no reported cases involving medical-use patents where manufacturers or sellers were found liable specifically for indirect infringement. In the existing cases, because the labels of the accused drugs explicitly disclose the patented indications, Chinese courts have generally held these parties directly liable for infringement based on their own actions, thereby obviating the need to analyze indirect infringement.

However, indirect infringement issues may arise in situations where the drug manufacturer does not include the patented medical use in the drug label or product information—such as in cases of off-label use. If off-label use falls within the scope of a patented indication, Chinese courts may in the future need to consider the potential liability of drug manufacturers under the doctrine of indirect infringement. Such cases may emerge as the enforcement of medical-use patents continues to evolve.

- Conclusion

Swiss-type claims are the standard mechanism for securing medical-use patent protection in China. Although the number of valid patents remains limited and recent years have seen a decline in grant rates, the continued growth in application filings reflects the increasing importance of this type of patent protection. To date, relatively few judicial decisions have addressed infringement of Swiss-type claims, but the existing cases provide valuable insight into how Chinese courts approach issues such as claim interpretation, infringement analysis, and damages assessment.

As judicial practice continues to develop, pharmaceutical companies should closely monitor these cases and take proactive measures when drafting claims and preparing enforcement strategies. A clear understanding of current enforcement trends will be essential for effective protection of medical-use patents in China’s evolving patent system.

Dr. Gordon Gao is an International Partner at King & Wood Mallesons. He specializes in intellectual property litigation involving patents, trade secrets, trademarks, copyrights, patent right abuse, end-of-patent-life litigation for pharmaceutical products, and appeals to the PRC Supreme Court for the above types of cases. Dr. Gao advises multinational technology companies on intellectual property protection and enforcement strategies and has handled many famous cases, including more than 10 groups of cases (a total of over 80 cases) on appeal to the PRC Supreme Court.

Dr. Xiaoyi (Sherry) Yao is an International Partner at King & Woods Mallesons. Dr. Yao specializes in intellectual property litigation, with a focus on patent invalidation and patent litigation. Dr. Yao is also proficient in advising on IP-related transactions. Her clients include well-known domestic and foreign companies across fields such as pharmaceutical, medical devices, and electronic communications.

Appendix: Summary of Medical-Use Patent Infringement Cases in China

| No. | Case Name | Case Numbers | Patent Numbers | Damage Award (RMB) | Summary of Judgment | Court of Trial | Level of Trial |

| 1. | Nanning Yongjiang Pharmaceutical v. Wuhan Tongshi Pharmaceutical and Yichang Sanxia Pharmaceutical | (2003) Nan Shi Min San Chu No. 75

[(2003)南市民三初字第75号] |

ZL93102915.5 | 400,000 | The court ruled in favor of the plaintiff | Nanning Intermediate People’s Court | First Instance |

| 2. | Huana v. Company S and Dalian Zhongxin | (2020) Zui Gao Fa Zhi Min Zhong No. 1158

[(2020)最高法知民终1158号]

|

CN200510068478.9 | 300,000 | The court ruled in favor of the plaintiff | Supreme People’s Court | Second Instance |

| 3. | Huana v. Company S and Dalian Zhongxin | (2020) Zui Gao Fa Zhi Min Zhong No. 1156

[(2020)最高法知民终1156号]

|

CN200510083517.2 | 300,000 | The court ruled in favor of the plaintiff | Supreme People’s Court | Second Instance |

| 4. | Wuhan Conform Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. v. Company Y Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. and Company Y Group Co., Ltd. | (2023) Jing 73 Min Chu No. 836

[ (2023)京73民初836号] |

CN200880111892.5 | 50,000 | The court ruled in favor of the plaintiff | Beijing Intellectual Property Court | First Instance |

| 5. | Shijiazhuang Development Zone Boxin Pharmaceutical Technology Development Co., Ltd., etc. v.Alcon Laboratories, Inc, etc. | (2010) Gao Min Zhong Zi No. 1647

[(2010)高民终字第1647号] |

ZL96190605.7 | NA | The court dismissed the case (the patent is invalided) | Beijing Higher People’s Court | Second Instance |

| 6. | Astra Zeneca (Sweden) Co., Ltd. v. Company R Pharmaceutical Group Co., Ltd., and Shanghai Qinmin Pharmacy Co., Ltd. | (2020) Hu 73 Zhi Min Chu No. 340

[(2020)沪73知民初340号] |

Not Disclosed | NA | The court dismissed the case (the patent is invalided) | Shanghai Intellectual Property Court | First Instance |

| 7. | Astra Zeneca (Sweden) Co., Ltd. v. Zhejiang Hisun Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Zhengzhou Pingchang Pharmacy Co., Ltd., etc. | (2020) Hu 73 Zhi Min Chu No. 341 [(2020)沪73知民初341号] | Not Disclosed | NA | The court dismissed the case (the patent is invalided) | Shanghai Intellectual Property Court | First Instance |

[1] Article 54(5) of the EPC 1973 provides that “[t]he provisions of paragraphs 1 to 4 shall not exclude the patentability of any substance or composition, comprised in the state of the art, for use in a method referred to in Article 52, paragraph 4, provided that its use for any method referred to in that paragraph is not comprised in the state of the art.”

[2] In HOFFMAN-LA ROCHE/Pyrrolidine Derivatives case, the Technical Board of Appeal (TBA) of the European Patent Office held that the second medical use lacked novelty and should not be granted patent, and that the inventor who discovered a new medical use of a known compound “should be rewarded with a purpose-limited substance claim under Article 54(5) EPC to cover the whole field of therapy”

[3] “A claim for the ‘use of compound X to treat … (indication) …’ is inadmissible under Swiss Law. Limited claims directed to the ‘use of a compound … to produce agents against …’ are admissible even where they relate to a second (or subsequent) medical use of a known medicament. Details concerning the formulation of a medicament (e.g. labelling, packaging or dosage) may be included in a patent application’s description.”

[4] Article 25 of the Patent Law of the People’s Republic of China provides that, “[f]or any of the following, no patent right shall be granted: (1) scientific discoveries; (2) rules and methods for mental activities; (3) methods for the diagnosis or for the treatment of diseases; (4) animal and plant varieties; (5) nuclear transformation methods and substances obtained in the method of nuclear transformation; and (6) the design, which is used primarily for the identification of pattern, color or the combination of the two on printed flat works. For processes used in producing products referred to in items (4) of the preceding paragraph, a patent may be granted in accordance with the provisions of this Law.”

[5] Article 25, Paragraph 1, Item 5 of the Patent Law (1984, expired)

[6] Article 25, Paragraph 1 of the Patent Law (1992, expired)

[7] Article 4.5.2 of the Section X in Second Part of Patent Examination Guidelines provides that, “[i]f the medical use of a substance is applied for a patent with such claims as “for treatment of diseases”, “for diagnosis of diseases” or “for use as a drug”, it belongs to the “methods for the diagnosis or for the treatment of diseases” in section (3) in first paragraph of Article 25 of the Patent Law and therefore cannot be granted a patent. However, since the drug and its preparation method can be granted patent rights according to law, the invention of the substance for medical use shall be patented by the claims of the drug, or claims of use claims belonging to the type of pharmaceutical process such as “application in the pharmaceutical process,” “application in the preparation of drugs for the treatment of a disease” and other use claims belonging to the type of pharmaceutical method. It does not fall under the circumstances provided in section (3) in first paragraph of Article 25. The use method claims belonging to the type of pharmaceutical process described above may be written as an examples of “The application of compound X in the preparation of a drug for treating disease Y” or a similar form.”

[8] Search Formula: TTL: (for preparation OR for production OR for synthesis OR for manufacturing) AND TTL: (treatment OR cure OR medical treatment OR prevention OR diagnosis OR therapy) AND TTL: (use OR application OR apply ) AND IPC: (A61 OR C01 OR C07 OR C08 OR C12) AND PN: (CN) AND APD:[19930101 TO 20241224]

[9] Explanation of search terms: Based on the typical expression of a Swiss-type claim, “use of compound X for manufacturing a medicament for the treatment of disease Y,” (1) the keyword “for” is added before keywords such as “preparation” to exclude patents for pharmaceutical preparation methods alone; (2) keywords such as “use” are used to define a use patent; (3) the IPC classification number is used to define the field of medicine.

[10] Data source: Patsnap Database

[11] Gao, F. P.: An Entitlement of Clinical Data: the Lega Framework of Clinical Data Sharing[J]. Modern Law Science,2020, 42(4), 52-68

[12] Statistics are based on valid patents granted from 2019 to 2023 in the Patsnap database.

[13] See: “Challenges and strategies for patent protection of new pharmaceutical uses (1) – Swiss-type claims” https://www.tip-lab.com/article/?uuid=6dc64ffae8594db8ab56f9b91059c3e2

[14] Statistical Monitoring Report on China’s Patent-Intensive Industries, published on the website of the China National Intellectual Property Administration, July 2024, https://www.cnipa.gov.cn/module/download/downfile.jsp?classid=0&showname=%E4%B8%AD%E5%9B%BD%E4%B8%93%E5%88%A9%E5%AF%86%E9%9B%86%E5%9E%8B%E4%BA%A7%E4%B8%9A%E7%BB%9F%E8%AE%A1%E7%9B%91%E6%B5%8B%E6%8A%A5%E5%91%8A.pdf&filename=f22e3c03ffc94bb09be8133f1bbb73bc.pdf

[15] Due to an 18-month delay between the application and publication of invention patents, current statistics will not reflect the volume of patent applications that have not been published.

[16] EIKEN v. DEAOU, the case numbers in the first instance: (2021) Yue 73 Zhi Min Chu No. 355