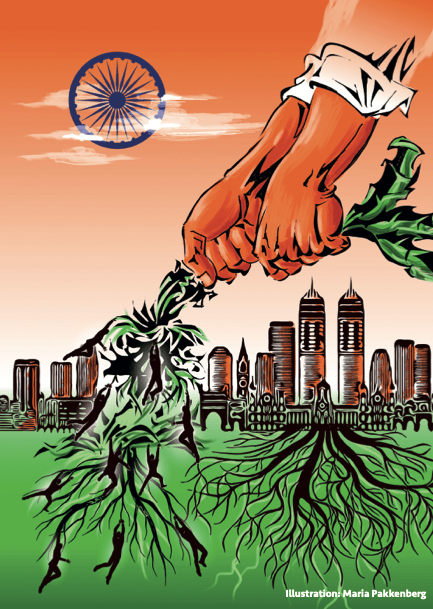

As the torchbearer of the BRICS economies since its successful globalisation project throughout the ’90s, India’s employment market has been the nexus of an enduring ideological struggle as the nation seeks to reconcile its socialist-era labour legislation with liberalised market policy.

The frontline of this struggle is seen in the extensive proposals for legislative reform currently being discussed and argued, with the nation’s employers and legal counsel now finding themselves at the centre of this crossroads.

On the one hand, the overbearingly protectionist laws currently governing employment in the organised sector have long provided security for employees, while employers have benefitted from the associated retention rates and company loyalty; on the other hand, the perception persists that these same laws stifle the foreign investment needed to sustain India’s upward economic trajectory.

Finding flaws in old laws

Evidently, the legal tensions need to be looked at in the context of the extraordinary societal changes that occurred as India shifted from the colonial British Raj to an independent state in the middle of the 20th Century – an independent state that had socialist principles at its heart.

These principles are seen reflected in the labour legislation introduced at the time, most notably the 1947 Industrial Disputes Act (ID Act), which still has considerable authority over contemporary labour issues.

Anshul Prakash, employment practice head at Khaitan & Co. – a firm that counts large domestic and international employers in the organised sector as clients – and associate Kruthi Murthy, say: ‘The ID Act, which was brought into force pre-independence for the investigation and settlement of industrial disputes, continues to be the parent legislation of most employment-related laws in India. However, said legislation has not previously been amended or revised to align with labour market trends in India.’

And what are the primary aspects of this legislation proving to be the most contentious in India’s fast-changing economic landscape? ‘The prominent villains of the ID Act in 2020 are Section 9A and Chapter VB,’ they suggest.

‘They make it impossible for an employer to effectuate any change without the consent of workmen. Furthermore, factories, plantations and mines engaging more than 100 employees must obtain the prior permission of the appropriate government before resorting to any layoffs, retrenchment or closure’.

However, that figure looks set to go up threefold should the latest suite of proposed reforms get the nod; the proposed Industrial Relations Code 2019 suggests a figure of 300.

It’s clear that these issues go far further than a contractual conundrum between employers and their workers; they’re becoming a point of focus in employment litigation before the highest arenas of India’s legislature.

Recent comments from the Madras High Court during an industrial relations dispute arising from a strike in the manufacturing sector also bring into light how the archaic nature of labour legislation isn’t keeping up with global workforce trends. Trends which India must adapt to.

A light is being shone on the transient and casualised nature of the modern worker. Most striking is Justice Venkatesh’s assertion that ‘the concept of a person working in a particular establishment or a company permanently is no more in existence. Right from the highest executives to the lowest level of workmen, they keep changing their jobs from one establishment to another always looking for greener pastures.’

Such statements show that India’s employment market is suffering the same teething problems as seen in the West, including the UK, when it comes to understanding the modern, transient worker, and legislating accordingly.

‘The industrial laws available in this country have become archaic and unfortunately, they have not changed with the fast-changing environment in the industry,’ Justice Venkatesh continues.

‘The law which does not meet the needs of the changing times and remains static, will prove to be more a hindrance than be of any help both to the employer and the employee. We have already reached such a stage.

‘Unfortunately the legislature, in spite of being aware of the situation, has not chosen to revamp the industrial laws and for reasons best known to them, continue to cling to the out-dated, absolute and outmoded industrial laws.’

While Justice Venkatesh may be accurate in his assessment of prohibitive blue-collar legislation, he could also look far closer to home for more significant stumbling blocks to India’s global potential, namely the infamously slow court system.

‘Approval of the appropriate government for layoffs, retrenchment or closure is not forthcoming and may be withheld for a prolonged period,’ say Prakash and Murthy. ‘In today’s era of digitisation and the fast-changing demand of global markets, swift adaptation to change is vital to maintain a competitive advantage. Delayed legal processes hampering workforce adjustments present serious challenges to profitability and business success.’

Whatever your ideology, an overworked and under-resourced court system runs antithetical to legislative progress. Prakash and Murthy put it simply: ‘The wheels of justice turn very slowly in India. Prolonged litigation and strikes organised by employees result in idle capital, loss of profits, delayed orders, and loss of goodwill from foreign investors.’

But although India’s snail-paced court system is much maligned – and certainly a recurring subject of ire for many employment lawyers who I interviewed – steps towards modernisation are being taken. And though it’s too early at this stage to tell, the post-Covid-19 world may actually bring in some positive changes when it comes to access and engagement with the court system, with technologies such as videoconferencing and e-filing coming to the fore.

Employment in the 21st Century

The global move towards casualisation and transience is no more pronounced than in the entrepreneurial technology sectors; sectors defined by innovative – and intrepid – employees both on the junior and executive level.

India’s prominence in the field of tech and innovation (particularly Bangalore, dubbed the ‘Silicone Valley of India’) has led to the sector becoming the new battlefield for industrial relations.

‘Unionisation in India is largely restricted to the traditional sectors such as the manufacturing industry, where labour unions have helped blue-collar workers with higher employment insecurity successfully negotiate higher wages, job security and other demands,’ explain Prakash and Murthy.

‘However, large scale lay-offs by IT companies, long working hours, automation and digitisation led the predominantly white-collar employees to organise themselves into trade unions in states such as Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Kolkata.’

Regardless, the traditionally blue-collar mechanism of collective action might not prove to be the most viable course of action in securing greater employment security and benefits for the burgeoning white-collar workforce.

One only needs to look to the original Silicone Valley to see how the specialised nature and sophisticated skill sets inherent in the tech and innovation sectors favour an employee’s market, as large employers throw around ever more competitive employment benefits and remuneration packages in an attempt to attract premier brainpower to their stables.

Should India’s similar workers recognise the utility of their highly specialised skillsets, unionisation might even prove to be more of a hindrance than a support, considering, as Prakash and Murthy suggest, that ‘the prominent effect of unionisation and its associated risk is a reduction of inflow of foreign capital.’ Capital needed to grow the tech sector and to provide sustainable employment possibilities.

‘Greater involvement of trade unions in the technology sector is likely to curb the flexibility of employers in terms of dealing with employee issues,’ add Prakash and Murthy. ‘By and large, it had stayed free of unionisation and unionism all these years, which is perhaps also why the sector has seen considerable domestic and foreign investment which in turn led to a greater number of jobs being created.’

The unorganised sector

The elephant in the room is the informal labour sector. Government and UN figures point to a total of over 84% of Indian workers being employed in the informal sector and contributing to 60% of the economy.

This is despite regulations and workers rights amounting to zero, with agriculture and manufacturing – sectors with a particularly high female workforce, and largely from rural communities – being disproportionately represented, raising the question of whether an over-regulated organised workforce could be to blame for such high figures.

‘Due to labour-market rigidity, establishments, especially those in the IT and services sectors, are looking towards the unorganised sector for engagement of independent contractors, freelancers, consultants or gig workers,’ say Prakash and Murthy.

‘Engagement of the unorganised sector is an attractive option as parties are free to agree on the terms and conditions to them based on the business needs of the employer. Further, since the unorganised sector is not covered under the compulsory social security laws there is less financial liability on the employer.’

Still, some nascent steps are being taken to increase protections for those employed in the informal sector. An opt-in National Pension Scheme has been floated by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government to aid workers in their retirement.

However, unlike in the US or UK, employers are not obliged to match contributions made by their employees. Instead, employee contributions are market-linked, and several investment instruments are made available. Furthermore, a mandatory 40% of pension wealth must be paid into an annuity to ensure lifelong payouts.

Gig-economy workers and platform workers (hired by the likes of Uber, Zomato, and other disruptive technologies) are also benefitting from a reform in the Code on Social Security which may pave the way for health and maternity benefits, life and disability cover, old-age protection, and other benefits as determined by the central government.

What the future holds

These are just a few of the Modi’s pro-capital reforms aimed at consolidating and simplifying the legislative jungle for employers. But, as Prakash and Murthy point out, ‘such labour legislations continue to predominately regulate and benefit only the employees of the organised sector.’

The centrepiece of these reforms comprises a set of four codes consolidating a previous set of 44. As might be expected of any red-tape reduction exercise, fundamental elements of the new legislation have been accused of stripping workers of the right to strike and unionise, specifically the new Industrial Relations Code which will subsume significant elements of the highly protectionist 1947 ID Act.

No better is the ongoing ideological struggle happening in India’s labour market better encapsulated than here. For while the legacy of worker protectionism is still apparent in much of the country’s organised sector, this mentality conflicts with the economic viewpoint that the foreign capital required to maintain India’s upward growth is hobbled by trade unionism.

However, given the ongoing global coronavirus pandemic, a cloud of uncertainty has been cast over the future of these labour reforms. Government statements suggest as much of a willingness as ever to pass the reforms, but to what degree they will resemble their pre-Covid-19 image is now uncertain.

The lack of social security in the informal sector was thrown into sharp relief by the mass urban exodus as workers returned to their rural communities once post-lockdown unemployment became a reality. This could provide the catalyst for a serious debate on long-overdue reforms to the informal sector.

Will socialist-era labour policies of old be subsumed by market-friendly reforms, or be built upon to adapt to the post-Covid-19 world order? This remains to be seen.