The Legal 500 sits down with leading Indian law firm, Legasis Partners, to discuss how the firm are handling COVID-19, and protecting in-house counsel facing an unprecedented crisis.

Legasis with its unique blend of professional legal services coupled with its legal tech solutions has not only kept up with the pace of rapid changes in ensuring legal compliances but assisting its clients in achieving these endeavours. The combined strength of Legasis Partners (Law Firm) and Legasis Services Private Limited (legal-tech company) has been providing clients with path breaking services by making optimum use of professional legal expertise and technology in delivering its legal services.

What differentiates Legasis Partners from the other contemporary laws firms in handling a crisis situation?

At Legasis Partners, we emphasise on providing clients with solutions to legal issues which are practical from their business perspective. Our focus is on understanding the nature of their operations which in turn helps us to provide pragmatic business-oriented solutions. Such an approach helps us resolve our Clients’ queries and issues whilst being in line with their needs in a cost-effective manner. The paradigm shift brought about by the recent COVID-19 outbreak has forced the staid legal fraternity to adapt to technology out of compulsion. However, at Legasis Partners, we are proud to say that we have been enthusiastic about the amalgamation of law and technology since our very inception. Being part of the Legasis eco- system and our sister company, Legasis Services Pvt Ltd, we have successfully managed the art of creating a fusion of IT and lawyering. The Specialised Business enterprise tools for legal compliance, litigation management, contract management and governances & ethics is a prime example of this philosophy.

The fact that we are a full services law firm and have been making an optimum use of technology is what sets us apart from our competitors. Our team of tech-savy lawyers were swiftly able to move to a ‘Work-From-Home’ model and continue providing seamless services from the comfort and safety of their homes. We strongly believe that modern technology empowers lawyers and helps them manage cases, clients, documents, teams and finances. We can confidently say that we have been able to deal with this world-wide crisis with resilience. “Innovation” is the buzzword of the 21st Century, despite resistance in the orthodox legal world. We believe we are here to change that!

Do epidemics justify non-performance of contractual obligations? And when does a company have grounds to look into a force majeure?

Force majeure emanates out of contracts and usually is included as a boilerplate clause in contracts to identify those events or circumstances which can neither be anticipated nor controlled and which may make the performance of contractual obligations impossible. The COVID-19 outbreak has brought business operations around the world to a complete standstill which has created roadblocks in the performance of contractual obligations. Epidemics may genuinely justify the non-performance of contractual obligations depending on the nature of the obligations and circumstances of performance/non-performance. For an instance, if a company is engaged in providing IT services to its clients, non-performance may not be justified. Whereas if a company engaged in manufacturing, non-performance may be justified due to e.g. disruption of supply chains. This will have to be determined on a case to case basis and unless the contract provides for force majeure, the same cannot be claimed as a matter of right under law. The government directives and guidelines may provide some insights towards interpretation. In India, the Ministry of Finance issued an office memorandum clarifying that the disruption of supply chain due to the COVID-19 outbreak should be construed as a force majeure event. Hence, insofar as contract with the government/government entities are concerned, COVID-19 received recognition as a force majeure event. However, for non-government contracts to be able to invoke force majeure, the contract necessarily needs to contain a force majeure clause in the contract to begin with. Furthermore, the contract should be holistically reviewed to ascertain the force majeure events that are enumerated in the contract and the associated clauses which set out compliances in order to claim an event as force majeure. In the absence of a force majeure clause in a contract, the company may invoke the doctrine of frustration enshrined in the Indian Contract Act, 1872. Alternatively, renegotiation of terms may be possible provided other relevant parties are open to it based on a sympathetic approach or past goodwill.

What are vital changes brought by the Firm to accommodate clients at the time of crisis? How has it benefitted the clients and the employees?

We have always had a flexible approach in our operations and this crisis was no different. The Firm analysed the situation and adopted ways to use technology to its fullest capacity. While the country was under complete lockdown and our Lawyers were compelled to work remotely, nevertheless the sense of responsibility and diligence, did not diminish. Wherever possible court hearings through video conference and meetings were undertaken. However, in case of urgency despite numerous hurdles the firm ensured physical filings and procuring orders by even visiting the judge’s residence. We also sympathised with our clients’ sudden financial crunch and gave them the flexibility of paying our fees to the best extent possible with an assurance that we could mutually address the deficit on normal resumption. This reassurance has helped in strengthening our trust and bonding with our clients much to their relief giving them the confidence that we stand by them in times of crisis. This way not only our litigation practice continued with minimal hindrance, but transactional practice also continued with minimum unease. Legasis was thereby able to advise a crowdfunding platform and helped close the deal whilst the country was in a complete lockdown. Similarly, the Real Estate Team at Legasis Partners acted as the Legal Counsel and Advisors for an acquisition of Real Estate for a Business Centre in Pune. All the Lawyers working were connected through digital mediums and concluded the task assigned, well within the time frame. We also implemented e-mail based unsigned document exchange in good faith with a condition that the physically signed documents would be made available as and when possible. This approach helped us continue contract and invoice delivery seamlessly based on digital documentation.

Necessity is the mother of invention and the Covid-19 Pandemic meant that we were flooded with mandates for analyzing contracts specifically whether or not the pandemic provided a force majeure defence to a party to the contract. This need of the hour led to the creation of a digital platform “Carrar Lite” specifically for such an analysis. Carrar Lite is Legasis Partners’ digital solution specially devised to review contracts that automates the contract review process from force majeure perspective. Carrar Lite is designed to provide opinions and advise based on their instructions and also delivers Notices under such contracts in a digitized manner. Some of the most noteworthy features of Carrar Lite are its Menu driven pricing and definite turn-around times. Our aim is to use technology to aid our best minds to help our clients in any given situation.

Can due diligence and honest efforts to foresee and prevent crises ever be enough, by themselves, to either avoid the ire of regulators entirely or significantly mitigate the consequences?

The importance of a due diligence exercise can never be discounted and it is always advisable to conduct a thorough check while entering into any kind of business transaction and the best way to analyze it is by conducting a detailed due diligence. It helps in providing some semblance of assessment to foresee any obvious or potential future risks going ahead. However, a due diligence is necessarily based on a pre-determined checklist which is

formulated based on existing legal systems with reliance placed on facts provided by the target. Hence, the success of the due diligence is reliant on the incisiveness of the checklist and depth of inquiries made which will have a bearing on the eventual outcome. Experience is a great teacher and definitely helps in improvising due diligence efforts every time but can never be a future predictor. Hence, besides the due diligence data recording, storage and processing in a manner to provide maximum possible analytical results holds the key to foresee a crisis. E.g. Had the Chinese Government in a transparent and concrete manner shared data pertaining to the Covid-19 virus accurately with the rest of the world, perhaps other countries would have been better prepared to anticipate the ill effects and counter the pandemic. Unfortunately, due to lack of proper data and the resulting confusion, by the time the world could make any sense of the virus or its deadly nature it was already engulfed by a pandemic. Nevertheless, despite the best of data gathering/processing and due diligence, there will always remain the limitation/risk of the unpredictable and unknown.

How has Indian Judiciary coped with the nationwide lockdown and measures taken to safeguard the interest of various stakeholders?

The Indian Judiciary has taken several measures to deal with the nationwide lockdown be it at the Supreme Court level, the High Courts, Lower Courts, as well as the Tribunals. These measures include but are not limited to conducting hearing of cases via digital means i.e. by way of videoconferencing. Initially the courts were hearing only limited urgent matters physically and the courts were functioning at low capacity. However, upon the cases of Covid19 seeing a significant spike and due to a nationwide lockdown being declared by the Indian Government, the Supreme Court as well as several High Courts have taken up “urgent cases” for hearing, thereby enabling Advocates to argue their cases over a virtual platform. Several orders and judgements have also been passed during the course of the lockdown on a host of essential subjects. Further, the process of filing fresh proceedings/ appeals have been streamlined and made possible using the online route thus avoiding the tedious process which comes along with physical filing. The Courts have also given leeway regarding extreme technicalities during the filing process and have been lenient with litigants when it comes to the issue of limitation. The courts have granted an extended period to litigants to file their petitions/ cases etc. to safeguard their rights and remedies during these troubled times. Judges have also taken miscreants to task by imposing heavy fines on those who tried to pass of their routine cases under the guise of urgency during the lockdown.

Certain lower courts have physically commenced functioning recently, albeit not at full capacity. However, such courts have to follow and implement strict guidelines laid down regarding observing social distancing norms. As stated above, the Courts have not been functioning at full capacity and have been hearing limited cases, mostly those of extreme urgency. However, the aforesaid steps have nevertheless helped in providing recourse to litigants even in these times of hardship. In addition, to the procedural measures taken by the Judiciary as stated above, the Courts have passed several orders/ judgments to protect the interest of various stakeholders. A few examples are orders passed by various courts to prevent banks from declaring certain accounts as NPA and providing borrowers an extended period for repayment of loan during this crisis. This in turn aids businesses in maintaining their working capital and cash flow to survive these turbulent times. Another such decision taken for the benefit of the public includes the Supreme Court regulating the price limit for distribution of Covid19 test kits, in order to make the same affordable to those in need. The government issued several labour related directives to ensure that the workers receive their wages and are not terminated from employment due to the current situation. Although the lockdown has been partially lifted, to avoid overcrowding and the resulting spread of the virus due to lack of social distancing, entry into courts is severely curtailed to only presence of essential persons.

How has the outbreak affected various sectors in India and what lies in the future ahead?

Unfortunately, the Covid-19 outbreak has left no stones unturned and has caused considerable distress in the political, social and financial structures around the globe, India being no exception. In India some of the severely affected industries includes real estate, automobile, tourism, shipping and infrastructure and the cascading effect of these sectors can be seen on the financial institutions. On the other hand, sectors like Pharmaceutical are performing relatively well and also the IT Sector where “work from home” was never a novel concept. The real estate sector has seen the maximum impact, especially with the shortage of labour and raw materials owing to the breakdown of supply chains. Most projects have been put on hold in spite of several government measures to ease the burden on builders. Similarly, several major infrastructure projects have come to a standstill. Travel and tourism, Hospitality, event management are a few sectors that have taken a huge hit due to the complete lockdown travel bans and prohibition of public gatherings across the country. Even though inter-state travel by airways and rail has begun, the same is not near full capacity. Thus, there seems no foreseeable boom in the near future. The automobile sector which was already in a severe crunch prior to the lockdown has been one of the worst hit. Several dealerships have had to shut shop overnight. Key players in the industry had to temporarily shut down manufacturing and even though some respite has been granted through government measures, the majority of the Indian auto industry is yet to restart their operations.

The lockdown and closure of courts has also affected the earnings of individual independent practising advocates relying solely on court proceedings with many facing a personal financial crisis. A countless number of daily wage earners employed in restaurants, hotels and the related supply chains have been rendered jobless due to the closure with bleak future prospects. Due to mass migration of the labour force from major cities to their villages due to the lock down, despite the partial resumption, businesses continue to face manpower issues due to labour shortages. The pharma sector however has been booming during this pandemic. E-commerce has benefited from brick and mortal operations coming to almost a standstill. Sales of essential products online have witnessed major booms. Owing to the dire situation with several industries, the financial institutions have also been directly hit.

The banks and Non-Banking Financial Companies (“NBFC”) typically lend to micro and small businesses with limited cash buffers, hence resulting in their inability to repay loans directly, which will in turn exert pressure on their lender’s operating performance and financial profiles. The Indian Government has implemented several strategies for protecting the Indian financial system. The government announced a stimulus program worth around US$ 23 billion to provide food and income security to low income households.

We can expect similar such public-welfare policies and schemes for the gradual return of economic activity. We have already witnessed that businesses which have adopted to technology are on the path of recovery but some sectors like hospitality, tourism, real estate, projects & infrastructure will remain weak for some time.

Authored by:

Gautam Bhatikar, Senior Partner

+91.22.6617.6500

[email protected]

This weekend marks the first London Pride weekend since the inauguration of the Middle Temple’s LGBTQ+ Forum at a launch event held in the Inn on 14 November 2019. This year – as with many aspects of life in lockdown – we have had to find creative ways to celebrate Pride remotely. That said, the opportunity now given to us to reflect is no bad thing. What follows is an abridged version of the talk I gave at the launch event in my role as vice-chair of the Forum, in which I set out my thoughts on why there remains a pressing need for LGBTQ+ visibility at the Bar; while made in the context of the Middle Temple, I hope that some of the points will be of more general interest.

This weekend marks the first London Pride weekend since the inauguration of the Middle Temple’s LGBTQ+ Forum at a launch event held in the Inn on 14 November 2019. This year – as with many aspects of life in lockdown – we have had to find creative ways to celebrate Pride remotely. That said, the opportunity now given to us to reflect is no bad thing. What follows is an abridged version of the talk I gave at the launch event in my role as vice-chair of the Forum, in which I set out my thoughts on why there remains a pressing need for LGBTQ+ visibility at the Bar; while made in the context of the Middle Temple, I hope that some of the points will be of more general interest. In the spirit of being a visible presence in the Inn, we have made a sign in the form of a pin badge incorporating the Forum’s shield, to be worn with pride.

In the spirit of being a visible presence in the Inn, we have made a sign in the form of a pin badge incorporating the Forum’s shield, to be worn with pride.

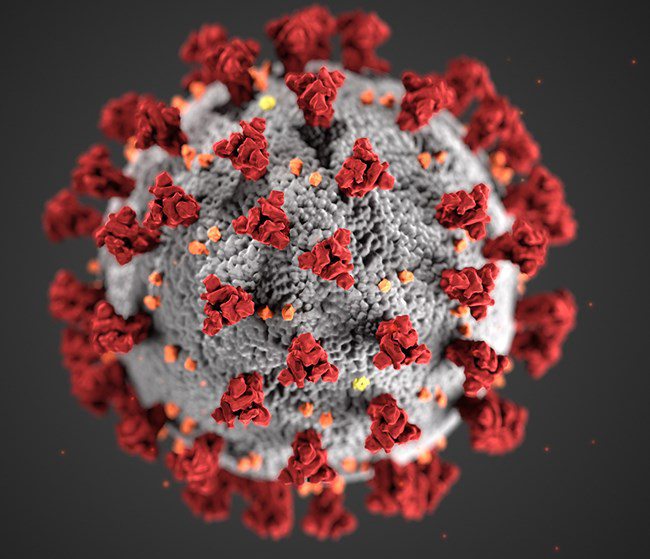

The disruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic has brought about the acceleration of several significant pre-existing trends, which are changing how law firms do business. For those involved in advising on dispute resolution, in particular, the pace of change in the use of technology and funding has been intensified. It is my view that many advantages of the specialist law firm, such as the potential for speedy decision making, the lack of competing practice area interests, and the opportunity for rapid implementation of new ways of doing things, have been highlighted by specialist firms’ willingness and ability to take advantage of developments in technology, and their engagement with the increasingly sophisticated funding market.

The disruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic has brought about the acceleration of several significant pre-existing trends, which are changing how law firms do business. For those involved in advising on dispute resolution, in particular, the pace of change in the use of technology and funding has been intensified. It is my view that many advantages of the specialist law firm, such as the potential for speedy decision making, the lack of competing practice area interests, and the opportunity for rapid implementation of new ways of doing things, have been highlighted by specialist firms’ willingness and ability to take advantage of developments in technology, and their engagement with the increasingly sophisticated funding market. The financial scars of the Covid-19 pandemic run deep. The new harsh financial reality means those who manage law firms face some tough legal questions. In my partnership practice, I have already seen the following questions arising as part of the ‘fallout’ from the coronavirus pandemic:

The financial scars of the Covid-19 pandemic run deep. The new harsh financial reality means those who manage law firms face some tough legal questions. In my partnership practice, I have already seen the following questions arising as part of the ‘fallout’ from the coronavirus pandemic: