From the famous advocates she worked alongside to the infamous clients she rubbed shoulders with, you cannot help but smile listening to Nemone Lethbridge, 85, recount tales of her life at the Bar. Yet smiles soon turn to incredulous laughter when she talks of chambers’ culture.

At a time when a spotlight is intensely focused on how women are treated in the workplace from Hollywood to Westminster, the question arises as to whether the Bar will have its own ‘Weinstein moment’. Appearing at the Spark21 event in November 2017 – an annual conference run by the First 100 Years project to remember the history and successes of women in law – Lethbridge recalled being treated with ‘total contempt’ by her law tutor because a woman going to the Bar in the post-war period was ‘laughable’.

By obtaining a pupillage, Lethbridge succeeded where many aspiring women lawyers of the 1950s failed, even if it wasn’t, by her own admission, on merit. ‘My father was the chief of intelligence in the Rhine Army in Germany and was investigating for war crimes and feeding information to the Nuremberg prosecutors.

So he became very friendly with Lord Kilmuir and he asked him to fix me up. It wasn’t on merit, it was pure nepotism.’ However, just because she had a foot in the door didn’t mean Lethbridge was set for an easy ride. On her first day in chambers a junior clerk was tasked with removing Lethbridge’s nail varnish, which had apparently caused some offense, and her pupil master, the late Mervyn Griffith-Jones, ‘bristled with embarrassment’ when she appeared beside him in court.

Nevertheless, she persevered, securing tenancy at Hare Court – the first woman tenant in chambers. But even there she found barriers in her way – literally – in the shape of a Yale lock on the set’s lavatory; only male members, who were each given a key, were allowed to use the privy.

Lethbridge, meanwhile, was told to ‘go up Fleet Street and use the Kardomah coffee house’ when she needed to answer the call of nature. This was not the only example of discriminatory behaviour the young barrister was required to endure. Her attempts to build a criminal practice were hamstrung as the then Scotland Yard solicitor ‘did not like women’, forcing her to take dock briefs and roam the circuits before getting her big break representing the Kray twins ‘practically every Saturday morning’.

But despite finally building a thriving practice – which included an appearance in the Court of Appeal at the tender age of 24 – Lethbridge was forced to leave the Bar after marrying convicted murderer Jimmy O’Connor. Once news of the marriage was made public in 1962 (having initially been kept a secret) Ian Percival QC, then head of chambers, ordered Lethbridge’s name removed from the set’s door.

She was, in his words, ‘no longer a suitable member of chambers’. It took 18 years for Lethbridge to return to the Bar, often being told ‘we don’t accept women here’. This isn’t the first I’ve heard of such stories.

Recalling her pupillage, Lady Hale – the president of the Supreme Court – told me in 2016 how her pupil master disapproved of female barristers because, he said, ‘the Bar is a fighting profession, not suitable for women’. And, in a separate interview, the late Sir Henry Brooke vividly remembered how some chambers openly ‘did not accept women tenants’ as a rule.

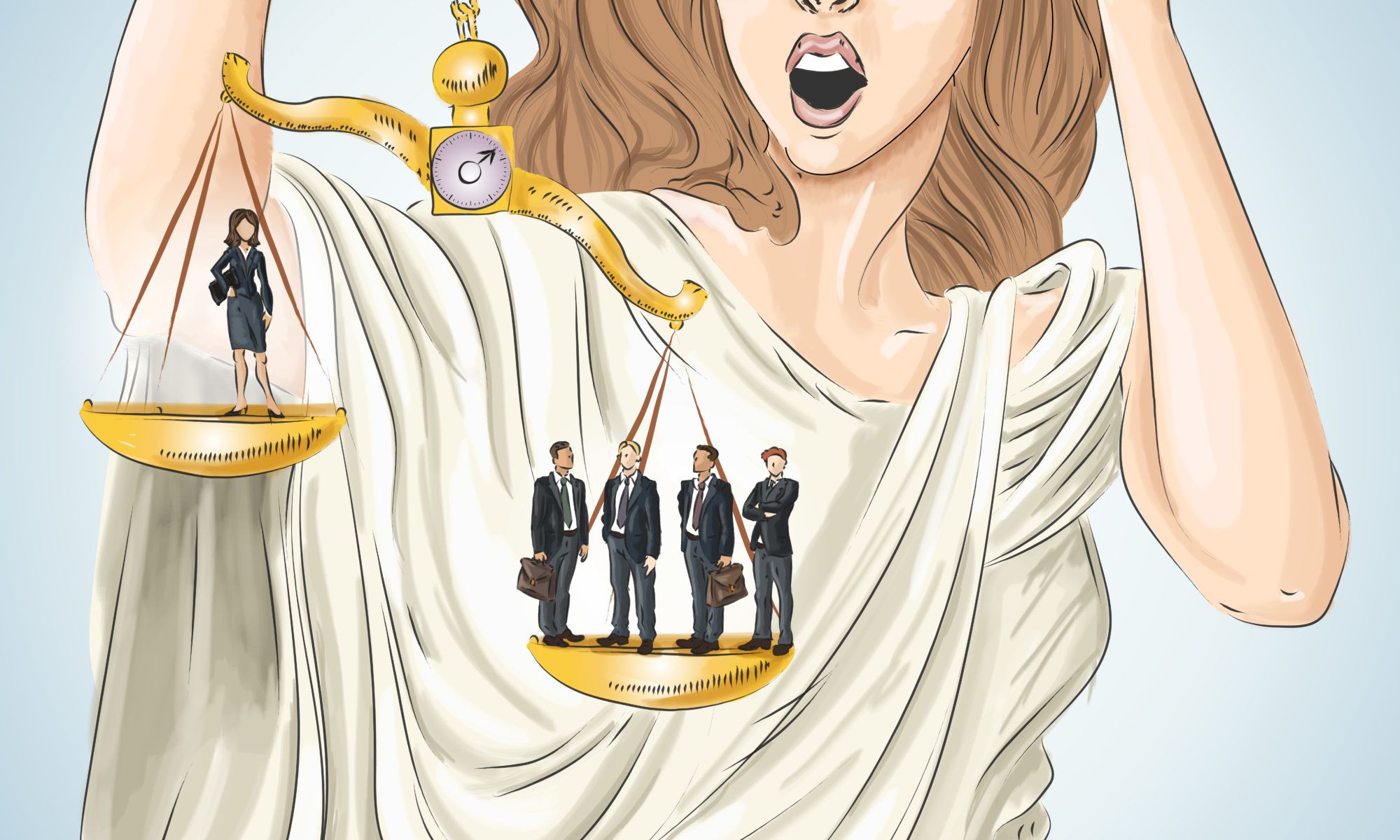

It would be easy to laugh off such anecdotes as the misogynistic echo of a bygone era; to convince ourselves that such instances of overt sexism were ‘acceptable’ back then as it was a ‘different time’, and that the modern Bar is a more diverse, inclusive environment for women. The statistics can tell a different story, however. Although more women than men now obtain pupillage (51% to 49%), tenancy is still weighted heavily in favour of male barristers (61% to 39%), and the disparity between the genders is even higher among silks (86% to 14%).

The reasons behind these statistics is well documented: taking maternity and parental leave is felt by many to have a negative effect upon a woman’s practice, with impacts on work allocation, progression, and income.

Discrimination and sexual harassment is also cited. While 2015’s Snapshot: The Experience of Self-Employed Women at the Bar report concluded that incidents of ‘recent’ sexual harassment in chambers were ‘rare’, it nonetheless led to the Bar Council releasing new guidelines to deal with such inappropriate behaviour.

In a Bar Standards Board survey published last July, two-fifths of women barrister respondents said they had been subjected to sexual harassment. Of those, only one-fifth went on to report it, with many others reluctant to speak out for fear it might damage their careers – a point recently reiterated by Baroness Kennedy of the Shaws QC. ‘It is still too hard for women to speak out,’ she told The Times. And yet some are finding their voice.

It has been reported that an independent review of how Matrix Chambers handled a serious sexual misconduct allegation found ‘institutional failings’ at the human rights set. The review by retired judge Dame Laura Cox followed a complaint by female barristers to the management committee about ‘sexualised remarks and insinuations made towards us by senior men at Matrix’.

Andrew Langdon QC urged victims of sexual harassment to ‘speak up’ and, as chair of the Bar, wrote to remind all chambers of the need for a ‘zero-tolerance approach’ to such behaviour. ‘Sexual harassment must not be tolerated at the Bar, or in any other walks of life,’ he wrote, while in office. ‘At the risk of stating the obvious, an allegation of sexual harassment is a serious matter.

It is incumbent on chambers, as a matter of fairness and to uphold the integrity of the profession, to treat the complainant and alleged perpetrator justly.’ Meanwhile, Behind The Gown – a Twitter account launched by a group of anonymous barristers – aims to start a conversation about the ‘endemic’ harassment and abuse of power at the Bar.

Only time will tell how successful such an initiative will be, but the more that victims are willing to speak out about their experiences, regardless of whether they are recent or historic, the more chambers will be forced to take appropriate action and root out inappropriate behaviour.

The Bar may not yet have had its ‘Weinstein moment’. But would anyone lay a bet that there isn’t one just beyond the horizon?