For many women lawyers, a long-term career at the top level of Big Law seems just out of reach. Even in 2019, the centenary year of women being allowed entry to the profession in the UK, it is still widely believed that women cannot ‘have it all’ and must eventually choose between having a family and a legal career. Diversity statistics from around the world reinforce that belief.

Only 18% of partners at the top ten UK law firms are women (PwC Law Firms Survey 2018), and (as highlighted in fivehundred Issue 02) Germany’s statistics are an even lower figure – just 10.7% of partners in top firms are women, as a 2018 report from the Federal Bar Association shows. Across the Atlantic, 47% of associates at the 200 largest US law firms are women, yet only 20% of equity partners and 30% of non-equity partners are female, according the National Association of Women Lawyers.

In Australia, just over one quarter of equity partners are female (The Australian Financial Review’s Law Partnership survey 2018), while in New Zealand women, who make up more than half of all lawyers, account for 31.3% of partners and directors. Looking at the 20 firms with the most partners, just five have a woman as CEO or managing partner (The New Zealand Law Society, 2018). The situation is similar in Hong Kong and Singapore, where out of the 20 largest firms only five are spearheaded by a woman.

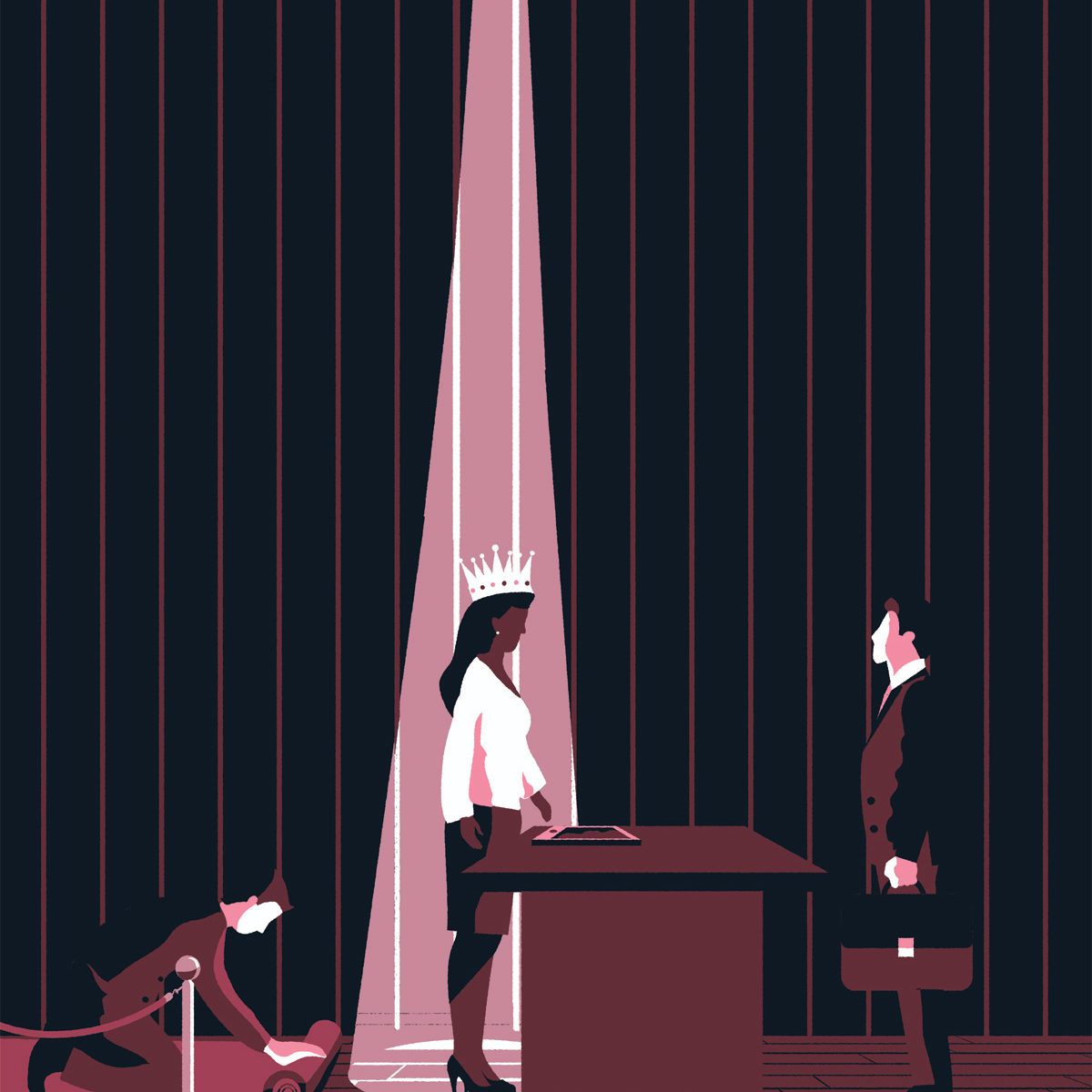

Yet, despite of the infamous ‘sticky floors’ and ‘glass ceilings’ prevalent in so many of the world’s most prestigious firms, some female partners have achieved tremendous success. How have they done so and what do they think needs to change for the next generation to succeed? To find out I asked a selection of female managing partners, practice heads, one law firm founder, and several senior lawyers across Europe and Asia Pacific to share their career secrets.

Of those I spoke to, many attributed their early career success to the presence of a strong female role model. ‘It is very important for women to be championed and encouraged to remain in the game,’ says Anne Grewlich, head of Ashurst’s global loans team in Germany. ‘Early in my career, a chance meeting with a female partner at an international law firm led to me being hired and taken under her wing as an associate.’

Not all lawyers are natural mentors and finding the right one can be as much about luck as it is a firm having a clearly defined mentoring strategy. For their part, women lawyers need to be discerning when making connections with female leaders and future mentors – be they male or female – must understand how mentoring women might differ from guiding men.

‘As women leaders, we understand that women do not always find it easy to promote themselves in the workplace and are perhaps more attuned to hear what our female team members have to say. It is very important to set an example,’ says Melissa Ng, an experienced mentor and corporate partner at Clifford Chance in Singapore.

‘We need to give female associates the assurance that there are prospects for career progression. The way we do that is for them to see women in the partnership, at the top of their game. But it is not just about work – our female associates not only want to see that we have successful careers, they also look to us to demonstrate that we can balance work and family and lead fulfilled, well-rounded lives.’

But setting examples is just one part of the challenge, and by itself often insufficient to push women out of their comfort zone. Several senior female partners underscore the need to allocate their mentorees challenging work; the kind that would intentionally stretch those with low confidence in their own abilities. These partners argue that mentoring, championing, and promoting women is not enough; it needs to be complemented by finding opportunities and putting women forward for awards and great, complex projects, too, and that mentoring programmes are only successful if everyone engages in them – both senior men and women.

Share the credit

In her 2013 best seller, Lean In, Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg opined that ‘the single most important career decision that a woman makes is whether she will have a life partner and who that partner is’. Suet-Fern Lee, Stamford Law founder and director at Morgan Lewis Stamford in Singapore, says: ‘You need to take mentoring diverse associates beyond the quarterly lunch. Bring diverse lawyers to client meetings and share the credit when you achieve successes.

‘In Asia, women of all races often face pressures from families, and after marriage, from mothers and mothers-in-law to step backwards in their careers. Many of them find it is helpful to have open conversations about challenges like this and the importance of getting their husbands on board and supportive.’

However, law firms need to provide the fertile soil for those women determined to climb the partnership ladder. This, of course, starts with the hiring process, which should include focused recruitment policies and target setting, according to some partners. ‘Having diverse applicants plays a role,’ says Ashurst’s Grewlich, ‘a firm which is known to encourage and value diversity should attract diverse applicants.’ This might just be the crux of the matter, however. Although not willing to go on record, a number of male managing partners told me how they struggle to attract female partners because their existing partnership makeup was either exclusively or predominantly male.

‘We do have female lawyers applying, and we would love to hire them, but when they see that they’d be the only woman in the team they turn down the offer,’ admits one law firm leader speaking on condition of anonymity. So women thrive under female leadership, but who is going to champion junior female lawyers if women are lacking in senior management roles? It seems like the proverbial ‘chicken and egg’ question.

Setting targets

For some, quotas are the logical solution to this problem. For others, they are an anathema to the supposed meritocratic nature of the law. Opinion remains split – even between women lawyers within the same law firm – as to whether the setting of strict diversity targets are appropriate for the profession and the impact their introduction would have on it; that real inclusion is not achieved by mandating it.

As an example of the differing views, while Barbara Mayer-Trautmann, managing partner of Clifford Chance Munich, believes ‘we can’t do without clear targets for how many women we want in management positions’, Bettina Steinhauer, a banking and finance partner in the Magic Circle firm’s Frankfurt office, thinks quotas ‘help if decision-makers are at least required to explain why women are underrepresented in a particular team, or why no female candidate is being put forward for counsel or partner in a particular year. This will help, but not lead to equal representation.’

In Singapore, Suet-Fern Lee advocates fishing from a much wider pool to reel in the best candidates: ‘It is important to look beyond the narrow role specifications for the particular position that one is recruiting for and keep an eye on how diversity will bring different skills and thought processes to the firm’s existing legal teams.’

Even if a more gender-balanced team is created, law firms can’t just rest on their laurels as unconscious bias must also be considered and combatted. Pattie Walsh, who co-heads Bird & Bird’s Asia Pacific employment practice out of Hong Kong, believes ‘it is essential to address unconscious bias and break down the traditional networks which perpetuate and support the progress of the limited participants through access to internal and client opportunities. There must be clear scrutiny of the way opportunities and progression are made available to everyone.’

Entrenched views on who is particularly suited to handling a certain type of work or acting for a specific type of client, affects how work is allocated and can hold women back in their careers. ‘There are many stumbling blocks for women and they start early in our careers,’ says Ashurst’s Grewlich. ‘For example, inequitable distribution between men and women of high-profile or billable work and low-profile or non-billable work, and potential biases in the application of pay scales due to differences in how men and women approach appraisals and

self-evaluate.’

To combat this, Walsh calls on individual partners to ‘actively support and challenge the women they see potential in, by helping drive their career in the direction they choose. This can be done by helping them present themselves in situations where their knowledge and skills can be showcased.’

Rani John and Gitanjali Bajaj, both dispute resolution partners at DLA Piper Australia, also stress the importance of ensuring unconscious bias does not prevent lawyers from developing relationships with clients. ‘It is important to give lawyers the confidence to shine when they do get that opportunity – accepting that women may shine in a different way to their male counterparts and that there is not just one road to success. It’s also about allowing for failure and ensuring that diverse lawyers have the same opportunities to learn and grow from their experience.’

The part time challenge

Melissa Fogarty, joint head of corporate at Clifford Chance London, thinks ‘we all need those more senior than us to encourage us to take the next challenge – to jump out of our comfort zones. I’ve benefitted immensely from the fact that colleagues have had confidence in me and my abilities well before I ever would have – I’ve been brave, sure, but it’s much easier to be brave when the people you look up to are steadfastly encouraging and give you that little nudge you need before you would otherwise be ready to say “yes”.’

However, being exposed to opportunities partly depends on being available to take ownership of work. Perhaps unsurprisingly, no other topic elicits as many differing views as part-time work. While part-time or flexible working can be convenient solutions, they can also result in lower pay and less visibility within and outside the firm.

According to Grewlich, Ashurst actively ‘challenges the need for women to choose between continuing work and raising children. In my team, for associates and paralegals, we actively promote part-time and job-sharing arrangements to overcome challenges with childcare. We want them to know there are still meaningful opportunities when they return to work.’ Yet, not every type of work lends itself equally to these arrangements: ‘It can be more of a challenge to accommodate flexible working in a transactional team with volatile and sometimes 24/7 work demands.’

At Clifford Chance, views on part-time career prospects are divided. Steinhauer in Frankurt points to the dearth of female lawyers at the senior level, ‘maybe partially because they were “overlooked”, but in many cases because they decide to work reduced hours to look after children or for work-life balance.’ However, Munich-based Mayer-Trautmann feels ‘it is crucial to have positive role models who demonstrate that a career is possible with a family, including part-time partnerships’.

Of course, it is worth remembering that beyond the firm/employee dynamic, there is also a third party to consider: the client. ‘We need to realise that we are a service provider,’ remarks Steinhauer. ‘Sometimes it feels our clients have a policy that supports work-life balance, but at the same time they want their usual contact person available whenever needed. We offer flexible part time arrangements and those that offer more predictable working hours, but only have a limited number of these positions.’ Connie Heng, who heads Clifford Chance’s Asia Pacific capital markets practice in Hong Kong, offers a nuanced view: ‘Having children or aging parents means you cannot be at 100% on all fronts all of the time. Women need to know it’s OK to pace themselves.’ At the same time she stresses the need for giving females colleagues ‘as much encouragement as possible, so they can grow professionally and challenge themselves’.

Overall, it seems women can have it all in Big Law; just not at the same time. At least, not yet. As a result, the debate over how to ensure a balanced gender split at the top of the world’s biggest firms will rumble on for some time to come. But while the current statistics are far from perfect, they at least show the profession is moving in the right direction, albeit slowly. That is at least cause for some celebration, as long as it is coupled with a renewed determination not to let the status quo continue. ‘Law firms are becoming more diverse, but it is happening at a glacial pace,’ says Suet-Fern Lee. ‘The battle for a fairer work environment is still very far from won.’