Foreword

After 40 years of misfortune, Iraq is desperate for a new start. Dictatorship, sanctions, foreign invasion, civil war and terrorism have left the country needing investment in almost every sector, and a virtually untapped market of 40 million consumers hungry for a new life.

For foreign investors with an appetite for risk, the potential rewards are high. But investing in Iraq is not a simple matter, and as anyone who has explored the market will tell you, finding the right legal and strategic advice is essential.

To gain an insight into the legal and business dynamics of the new Iraq, The Legal 500 partnered with Al Tamimi & Company for this special report, surveying over 100 legal counsel and foreign investors currently active in the country. The results were surprising.

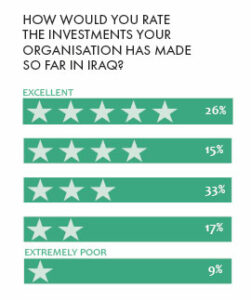

Over a quarter (26%) of respondents rated the outcome of their investments as excellent, with only 9% rating them as extremely poor. The scale of opportunity Iraq offers was also clear, with 40% of those surveyed citing a lack of competition as the chief reason for their investment.

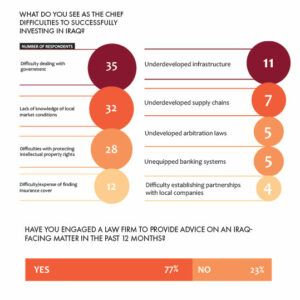

Of course, the challenges and risks presented by Iraq were also widely discussed. Dealing with government authorities was reported as a chief difficulty faced by 35 of the companies surveyed, while understanding local market conditions (32 companies) and protecting intellectual property rights (28 companies) were also pressing concerns.

The fact that practical challenges such as underdeveloped supply chains (reported as a chief difficulty by just seven companies) and obtaining insurance cover (12 companies) – issues that even the largest multinationals have struggled with – were so low down on the list of concerns, only serves to highlight just how undeveloped the market is.

Over three quarters (77%) of those surveyed had taken legal advice on their investments, with most looking for help dealing with government departments and ministries (38 respondents), understanding the licensing regime (42 respondents), establishing an office or branch (52 respondents), and advice on tax (47 respondents).

It all adds up to a complex picture of a market where opportunity and risk are often inextricably linked. To help cut through the chaff, we have drawn on a number of experts, including general counsel with expertise in Iraq, Al Tamimi partners who have helped businesses thrive in challenging conditions, as well as frontier investors who are betting on the country’s growth.

We have also tried to shine a light on a different, lesser-known side of the country by documenting its nascent start-up scene and examining the prospects for a young generation of Iraqis who find themselves in a country that is finally open to the world. Above all, we present the views and lessons of those who got it right, and those who got their fingers burned. As one GC commented, ‘No one says it’s easy to do business in Iraq, but it’s not impossible either. Learning from the mistakes of others is the quickest route to success.’

The Legal 500 In-House Legal Research Team

John Anthony Tucknott MBE

The Legal 500 speaks to Tucknott, British Deputy Ambassador to Iraq and UK Trade Champion, about the opportunities available to UK businesses in Iraq.

Anthony Tucknott MBE was appointed British Deputy Ambassador to Iraq in 2017. He was formerly British Ambassador to Nepal, British Deputy High Commissioner, Karachi and UK Trade and Investment Director for Pakistan. Between 2007 and 2009 he served in the British Embassy in Iraq, and has followed the country’s development ever since.

‘What amazes me is the resilience of the Iraqi people, who have endured 40 years of sanctions and conflict, and the hope and belief they have in a better future for themselves, their families, their nation and their country,’ says Tucknott. ‘I know that all of us working for the British Government in or on Iraq are determined to do all we can to assist all Iraqis to achieve their aspirations and dreams.’

The British Government’s commitment to help make the country a success is also good news for UK businesses looking to build trade ties with Iraq.

‘UK Export Finance (UKEF) has announced an additional £1bn of support for projects in Iraq, giving UK companies operating in Iraq huge advantages, as prime contractors seek to ensure there is sufficient UK content in their supply chains to meet UKEF’s requirements. The Department for International Trade (DIT) Iraq and the Iraq-Britain Business Council (IBBC) stand ready to support any UK company preparing to enter, or looking to grow its presence in Iraq.’

For those businesses willing to take the plunge, the benefits could be vast.

‘There are substantial opportunities in Iraq for UK companies in a variety of sectors. Over the coming years, Iraq will embark on a huge programme of projects to develop and rehabilitate the country’s power and water infrastructure. These will provide business opportunities requiring the expertise of British construction, engineering, electrical and project management companies, to name but a few. Following the traumatic years of the fight against Da’esh, Iraq is looking to modernise its armed forces and its government administration; this will create opportunities for companies providing professional services, business process outsourcing and a range of consultancy services, in addition to those traditionally supplying the defence sector.’

While the 200 or so UK businesses currently operating in Iraq provide highly-specialised engineering, oil and gas projects, or defence and security services, the opportunities for business are far more widespread.

‘Iraq is a challenging market to enter, and larger companies or those with greater risk appetites have traditionally led the way. But this should not put off smaller companies or those outside of the security and oil and gas sectors, providing they engage intelligently with the support available. This is particularly the case for companies who already have operations in, or experience of, the Middle East. DIT actively supports prime contractors to identify UK suppliers. Attending a DIT roadshow event, trade fair or visiting the Business Opportunities Website are the best ways of identifying specific opportunities to supply established players in the Iraqi market. IBBC and DIT can then provide advice on identifying the best local partners and overcoming market access barriers.’

‘In addition to major infrastructure and defence projects, there is a large and growing demand for British goods and services among Iraq’s increasingly prosperous middle class, particularly in education, in which UK qualifications are a source of great prestige, and in the country’s booming retail sector.’

Even with the government support, businesses should be prepared to undertake enhanced due diligence on their proposed activities.

‘The biggest problems faced by UK companies entering the Iraqi market are: lack of business intelligence about the opportunities available; navigating the bureaucratic and regulatory system to obtain permissions or get contracts signed; corrupt, arbitrary and inefficient customs processes; and finding the right local partners. DIT and IBBC can provide support to navigate or mitigate these challenges. But British companies looking to enter the Iraqi market should prepare themselves for a challenging business environment.’

And while the state will remain the dominant economic actor in Iraq for the foreseeable future, the Iraqi Government is looking to encourage investors to works with the country’s private sector. ‘Iraqi Ministers are aware that bureaucracy is stifling Iraq’s economic development.

Many hope that privatisation and outsourcing offer a way to stimulate greater international trade and investment. This is likely to mean that private companies will play a bigger role in Iraq’s economy in the future than they have traditionally. However, they will, for the most part, be chasing government contracts. The growing retail sector, along with healthcare, education and financial services, are likely to be the areas in which a genuine private sector will have the space to emerge in the years ahead.’

Unlocking a new future

For the first time in nearly 40 years, the outlook in Iraq is bright.

The fall of ISIS, which nearly broke Iraq apart and consumed its resources in a three year fight, has finally brought a semblance of political and financial stability. While the political situation in neighbouring countries – particularly Syria and Iran – will have a huge impact on Iraq’s ability to progress, improvements in domestic security have transformed the country’s prospects. Meanwhile oil, the country’s main source of income, is once again on the rise.

For investors, the scale of the opportunity is clear: a population of over 40 million, roughly 70% of whom are below the age of 30, is coming back to the world stage. As Mohammed Norri, a partner in the corporate commercial practice of Al Tamimi and head of the firm’s Baghdad office, puts it: ‘Iraq has been starved of investment in every single sector of its economy since 1982. Whether it’s healthcare, education, oil and gas, or industrial production, there are opportunities everywhere. What Iraq offers investors, almost uniquely in the global market, is an opportunity to invest and see growth for the next 50 years.’

There are other signs of this growth potential, adds Zaab Sethna, co-founder of Northern Gulf Partners, one of the few frontier funds to specialise in Iraq.

‘The figure we like to use as a benchmark is the total market capitalisation of the stock exchange to the gross domestic product (GDP) of the country. Iraq’s market cap today stands at around $11.7bn, which is under 6% of the country’s GDP [of roughly $200bn],’ he says.

‘The closest comparable country in terms of population, geography and reliance on oil is Saudi Arabia, which has a market cap to GDP ratio of 75%. That shows you there is tremendous potential for growth in Iraq. That’s the story we are investing in.’

Mohamed Hawary, director of investment for the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) at GroFin, an investment fund manager specialising in the finance and support of small and growing businesses, sees a similar scale of opportunity.

‘If you throw a dart almost anywhere on the board you’re going to be successful because there are opportunities in every sector, from food production to entertainment,’ he says.

‘Iraq has the highest investment potential in the MENA region simply because it’s coming from such a low base. Even a small improvement in stability or infrastructure will make a big difference and you will see growth in a relatively short space of time.’

Of course, opportunity is only part of the story.

While fledgling businesses may have a good grasp on the scale of the opportunities available, implementing and realising those opportunities can too often be another story all together. The challenges apparent are vast: finding and retaining talent, navigating a complex legal and governmental framework, in addition to starting-up in a country still finding its feet on the global stage.

‘Iraq is a phenomenally difficult place to invest, but that’s why you employ a lawyer. You say to them, “find a way to overcome these challenges so that we can capitalise on this growth story,”’ says Mohannad Al Nabulsi, general counsel of Samsung Electronics Levant.

For those willing to take the risk, now is the time to get in. Those taking a ‘wait and see’ approach may find the most interesting opportunities disappear rapidly.

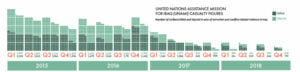

NEW BEGINNINGS

One of the biggest drivers of investor interest has been the dramatic improvement in Iraq’s security situation over the past two years. The number of people killed in acts of terrorism and conflict-related violence fell from over 7,500 in 2015 to under 1,000 in 2018, while the number of people injured showed a similar decline, falling from nearly 15,000 in 2015 to around 1,600 in 2018. These improvements in domestic security have transformed the country’s prospects and led to a rise in interest among investors.

‘We used to receive two or three enquires a month from companies interested in setting up or investing in Iraq,’ says Norri. ‘Now we receive around five a week, with a big increase from entities outside of the GCC [Gulf Cooperation Council].’

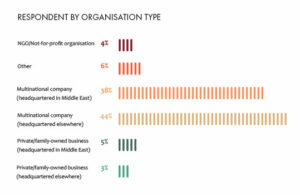

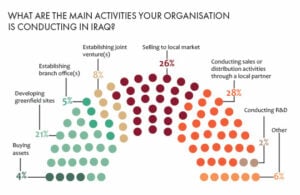

To get a sense of the challenges Iraq presents, we surveyed over 100 senior legal figures across a range of industries, with 88% of those surveyed currently operating in Iraq. The bulk of those we surveyed represented multinational organisations headquartered in the Middle East (38%) and elsewhere (44%) and reflected an investment landscape still dominated by construction (19%), and energy – including oil and gas (35%).

Crucially, the results show that security concerns are no longer dominating the risks monitored by investors. While 28% still saw security as the primary risk to investing in Iraq, far more (40%) were monitoring the risks arising from corruption, while nearly a fifth (18%) were concerned with the lack of protections offered to investors. For many businesses we spoke to, these challenges are just the start.

‘We operate in some challenging jurisdictions, but I would classify Iraq as toward the top end of the scale when it comes to legal, operational and logistical complexity,’ says Christina Ibrahim, executive vice president, general counsel and corporate secretary at multinational oilfield services company Weatherford.

‘Considerations about safety of personnel and how to move them around the country come into play constantly, but the bigger difficulties come from a lack of transparency over processes and requirements when dealing with government authorities. The term “developing market” is accurate here in more ways than one: the country is always changing and the operating requirements can change quickly and without notice. Even for experienced counsel it can be difficult to get a clear understanding of the rules of the road.’

Simon Nai has spent the last 12 years in Iraq, where he heads the legal and audit department at Chinese oil giant CNOOC. While progress has been made, he admits that it can still be a struggle to understand what is required by law.

‘Legally, Iraq is not an easy place to operate. Many laws and regulations date back decades, and new laws are published regularly. Some of these follow the original civil code, others have a more Anglo-American style overlay. The result is a complex and sometimes contradictory set of laws that are complicated further by difficulties with health and safety, employment, and visa requirements,’ he says.

‘There is also a large number of government ministries in Iraq, which can make it difficult to know what to do in any given situation, particularly when different authorities have different interpretations of the requirements. After many years, I am getting more familiar with the Iraqi operating environment, but as for the exact provisions of the law I cannot say I understand all of them. Frankly, I do not think anyone does.’

A further challenge is highlighted by Koray Koҫak, general counsel at Taq Taq Operating Company (TTOPCO), a joint venture between UK-based Genel Energy and China’s Sinopec operating in the Kurdistan region of Iraq. He has found, like many GCs in the oil and gas sector, that the pressure to use local contractors can create compliance challenges.

‘There is a consistent demand placed on oil and gas companies in all geographies to work with local companies and employees, but in an Iraqi context, “local” can mean belonging to a particular group or village. We do acknowledge that multinational companies need to help build capacity, but it remains one of the biggest risk exposures any international business faces.’

Ibrahim adds: ‘Local content requirements can be very difficult if you want to run a technically complex project that requires skilled labour. It is a challenge to find qualified individuals or to train people to the required standard, which can have health, safety and security implications. It is also a business challenge. Building a processing facility requires a lot of technical expertise and it is rare to find it in remote locations.’

While giving preferential treatment to local contractors is widespread across the Middle East, it presents far greater challenges in Iraq, and not only for those operating in the oil sector.

‘Manufacturing facilities are either not available or of a poor quality. The insurance costs are high, it is extremely difficult to move goods or components around the country, and for certain products you will need international approvals or certifications, which are almost impossible to obtain from within Iraq,’ says Zeid Uteibi, head of legal for the MENA region at Hikma Pharmaceuticals.

‘The solution the government appears to have come up with is to apply regulations that bypass the local manufacturing regulations, allowing you to import semi-manufactured goods that are simply completed at a site in Iraq.’

A COMPLEX ENVIRONMENT

Even when products can be imported and distributed, businesses will find they need to meet regulatory requirements that can seem bizarre. As one GC commented, ‘We operate a franchise for a chain of cafés across the region, but we can’t get chocolate chips for the cookie dough into the country. There is no standard defined for cookie dough, which means it can’t be imported. That’s how it works.’

Mohamed el Roubi, general counsel at the international division of international security contractor GardaWorld, has a wealth of knowledge when it comes to operating in Iraq. In 2003, the then Egypt-based el Roubi decided to take a risk and help set up a law firm in Baghdad. He has since continued to follow the market with interest, and regularly oversees GardaWorld’s investments in the country. Too often, he says, the regulations act as a barrier to investment.

‘Almost all industries are heavily regulated, which means you will need to obtain licences and sub-licences from a large number of ministries. In the security industry you need a licence from The Ministry of Trade, but they won’t register you as a company unless you have approval from the Ministry of Interior. Before you can operate you need a licence for weapons, a licence from the telecoms regulatory authority for the frequencies of your radios, plus a licence for the tracking systems you put in your vehicles. It’s just endless,’ says el Roubi.

‘All the licences will have been obtained at different times, which creates a massive administrative burden, as you have to constantly monitor which ones are expiring and which are still active. If I were a foreign investor, I’d look at the licencing situation and think there’s easier money to be made elsewhere with less risk. The government should engage with proper investment thinking and simplify the whole process to become a one-stop-shop that covers all activities.’

FINDING SOLUTIONS

At Al Tamimi, the firm has been working to support various non-governmental agencies, and the Iraqi government, to help improve the understanding of international investment laws, but there is still a long way to go.

‘The investment laws needs to be amended, the companies’ law needs to be amended, the visa laws need to be amended. A lot of these laws can discourage investment for no real reason,’ says Norri.

‘For example, under Iraqi law each company must appoint a single, named manager. Certain companies will have a policy that says there must be two signatories to any amount above $100,000, which is not permitted in Iraq. It is not reasonable to enforce laws at this level of detail. A company should be free to operate in the way it thinks best. This type of bureaucracy becomes burdensome on those who wish to operate in the country.’

Operating in a country that is heavily bureaucratic, where government processes can be confusing – even to those who have spent years in the market – and where legislations dating back to the 1970s can block business on seemingly illogical grounds, frustrated many we spoke to. Indeed, it was notable that only 14% of those we surveyed considered currency fluctuation and market volatility to be the chief risk they would face in the market.

As Uteibi comments: ‘On international investments, I will usually act as part of an advisory team looking at commercial and financial risks such as currency fluctuation or devaluation. When it comes to Iraq we don’t even get that far because we are still looking at basic things like security and how to move products around. It’s just a very different world.’

He adds that acting for a UK-listed multinational means keeping on top of the UK Bribery Act and other anti-bribery and corruption laws is top of his list of concerns. ‘The Serious Fraud Office reviews a lot of the work done by companies active in Iraq, which means you have to have a very sharp eye and be very prudent when it comes to business partners. The most important thing is to make sure you have an audited and credible business model to ensure compliance with the regulatory requirements.’

Another GC we spoke to, who wasn’t authorised to comment publicly, characterised it even more starkly: ‘If I were a financial adviser I would not advise my clients to go anywhere near Iraq. If anything goes south, there are very few options available to get your money back. Besides, most of the big money is government-related, typically through state tenders for big projects. It can be very tough to succeed in the market and unless you absolutely have to be there I would explore other options first.’

In such a tough market, getting close to government decision-makers is essential. A number of those interviewed for the report commented on the difficulty of conducting legal matters on paper – rather, personal relationships were key to progressing matters – making a local presence a necessity.

‘Matters need to be followed up personally. There have to be some control points on each step and local authorities should be informed prior to the process so they have your general objectives in mind,’ says Koҫak.

‘You also need to manage the local media and popular representative bodies; if they are not on your side a project will almost certainly fail.’

Norri adds: ‘Typically, we are not only advising on legal matters when it comes to investments in Iraq. Beyond understanding the law, clients want to know how the government or larger private sector companies will respond to a particular plan. We can tell them which laws are applicable, but more importantly, we can tell them what to expect.’

It is a view shared by Paul Bailey, founder of Devonport Capital. Before setting up UK-based Devonport, a specialist lender that provides bridge-financing to SMEs operating in Iraq, Bailey worked as both a lawyer and investment manager in Iraq.

‘When I first moved to Iraq in 2007, legal advisers worked almost exclusively with multinational clients,’ he says. ‘Today, if we review the contracts our borrowers have or engage in investments directly, it is almost always the case that both the international and Iraqi party has appointed a lawyer, often from an international firm. More and more people see the lawyers as a value-add, in terms of clarity and professionalism, and the sophistication of business is improving rapidly.’

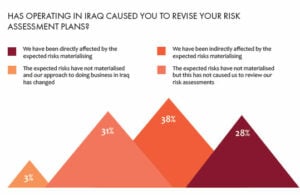

However, perceptions will take a long time to change. While around a third of those surveyed (31%) had not seen the anticipated risks materialise in Iraq, only 3% had changed their risk assessments in response to a more favourable operating environment. Indeed, only 28% of our survey respondents had been directly affected by the expected risks materialising, with a further 38% having been indirectly affected by the expected risks materialising (by experiencing disruption to supply chains, for example). As Al Tamimi’s Norri concludes, ‘there are lots of success stories in Iraq, it all depends on the right approach. A long-term investment strategy will pay off in the end. This is what has been proven so far.’

CAPACITY BUILDING IN IRAQ

While the buying power of the Iraqi government is tremendous and tenders remain lucrative, it has recognised that the country needs to open up to new sources of capital and break its dependency on oil. Already there are signs of change, with a flurry of new franchises entering the country.

Mais Abbas Abousy is attorney-advisor with the Commercial Law Development Program (CLDP), a technical assistance programme from the US Department of Commerce. As part of her role, she has been working to encourage franchises to locate to Iraq and says the spread of Western brands across the country will ultimately help sell it to investors.

‘It may sound funny, but if you’re an investor and you think about a country and it doesn’t have a Starbucks or a McDonald’s, you’re going to view it as underdeveloped. These things may seem trivial, but they make a big difference to how we see a place,’ she says.

Beyond this, she adds, the market offers great potential for franchise operators.

‘People can be sniffy about the idea of opening a franchise in a country like Iraq, but look at the scale of the opportunity. Retail is in decline in most cities across the world, but there are seven shopping malls in Baghdad and the visitor numbers are staggering. After years of troubles people want to go out and enjoy life.’

A further sign of optimism, she notes, comes from the increasingly sophisticated operating environment.

‘Major international law firms are now front and centre as consultants to the Iraqi government in their negotiations with oil companies. Five years ago it was frowned upon to use outside counsel, now they are sought out, vetted and procured. That represents a huge shift in the Iraqi business climate. Few people have realised how important this is. Instead of looking at what went wrong, we should recognise the rapid maturation of Iraq as a market,’ she says.

‘Our work is focused on strategic consultation or legal consultation with governments. We work through closed-door discussions on international standards and how to apply them. We’ve worked with a number of emerging markets who have been through the same lessons, so our philosophy is to work with governments and look at how we can shorten the learning curve as much as possible.’

Zaab Sethna, Partner, Northern Gulf Partners

A former adviser to the Government of Iraq following the fall of Baghdad, Sethna shares his perspective on what is needed to return the country to prosperity.

I worked in the Iraqi government from 2003 to 2006. I was a consultant in oil and then in finance, before I left to work in the private sector. During my time working for the government I’d signed up some foreign companies as their door-opener in Iraq.

What I realised by engaging with both these companies and the government, is that firstly, there is great potential for Iraq, a country that while currently impoverished, is one of the few on the planet that can lift itself from the ranks of the poor to the rich. The capacity is there. Secondly, it needs everything in every sector – the country has been cut off from the world and subjected to every bad idea known to mankind in the twentieth century.

Iraq is going through two transitions at the same time – from war-torn to post-conflict and from centrally-planned to free market. It’s fiendishly difficult to manage these two transitions at the same time.

Iraq has natural resources, fertile land, intelligent people, a long history of urbanisation, and world heritage sites. It’s been a victim of bad management, but that is slowly improving. There is some good human potential in Iraq, too. There are companies which are market leaders; there are families that have been in business for generations; there are young people with start-up ideas.

What they are all starved for is capital. There is no source of financing in the country. The banks aren’t lending and the government has little knowledge of the private sector. They are also starved of international links – they’ve been cut off from the outside world for a generation. They are starved of modern management skills and know-how.

Corruption is an issue but I see movement in a positive direction. Irregular enforcement of rules and laws is another problem, particularly from a foreign investor standpoint. The bureaucracy is very strong, but it’s not very capable or competent, which I think is a legacy from a dictatorial regime. When it’s a dictatorial regime, one in which you can lose your life for making a decision, you cement in a culture of doing nothing. To an Iraqi bureaucrat the default answer is always ‘no.’

People don’t realise that per capita GDP in Iraq has more than trebled in the last ten years. It’s roughly $4,000. It was $900 in 2003. It’s out of the impoverished zone and heading toward middle income. After the oil sector, the second largest flow of money into Iraq is Iraqi expats sending money back in. They know the country and know the potential, maybe they also feel they can mitigate the risks with their own local knowledge and networks. A lot of businesses like private medical clinics are founded by Iraqi doctors abroad who see the opportunity.

It’s impossible to put a date on when returns will come or to set horizons, but what we can do is look at other post-conflict societies and track against their development. Nothing is a perfect guide, but you can make predictions.

Mohamed el Roubi, General counsel, GardaWorld International Protective Services

Initially moving to Iraq to set up his own firm and assist in the reconstruction efforts, el Roubi shares the benefit of his 16 years’ experience in discussing how the country is developing for business and investors alike.

I first moved to Iraq in 2003 to start a law firm. It wasn’t me who saw the opportunity, but rather, a partner that I worked for in an Egyptian law firm. He went in May of 2003, following the fall of the Saddam regime. We had the idea that Iraq was a country that was going to undertake a massive reconstruction following a rather devastating civil war, combined with years of sanctions and neglect. By June 2003, I was there. We found an Iraqi partner, created a three-way partnership and set to work!

There’s definitely been a positive progression in Iraq. There were some particularly bad years – 2006 and 2007 come to mind. But even before then, when the insurgency truly got going, I had in my mind that there would be an active period of perhaps five years of really bad violence that would eventually simmer down to a relatively stable country like Turkey, with just pockets of instability. Now what you have is a democracy that’s sort of dysfunctional. It’s not properly technocratic – that base is still developing – but it’s getting there.

What you see as an investor is that during periods of political disagreement, the decision-making process gets suspended and you get periods of hostility toward, or mistrust of, investors. But having been through a few of these cycles now, I am starting to see a pattern form where, even though it can be a slightly dysfunctional process with horse-trading, there are rules and arrangements for how it plays out.

However, I see reasons to be optimistic. Iraq’s younger generation now live in a completely different world. Iraqis are very smart people with a voracious hunger for information and technology. That is absolutely a positive sign for the country.

The law is a bit outdated, but there aren’t a lot of surprises. The problem is when you get into new areas of commerce and investment like technology and intellectual property rights, all the things businesses depend on today. You need to have an interpretation of how those provisions of the civil code apply to this matter – particularly in disputes, this is a problem.

In a world of technology, where you have royalties and income offshore for example, that’s where there is a lack of sophistication and where the lack of a technocratic base in government is a problem, rather than the state of the law itself. The government is not going to rush ahead to develop new business-friendly laws because they themselves don’t understand it. These are party lists that are heavily religious or ethnically dominated that have a different priority. That will be a problem going forward.

STARTING-UP A NEW IRAQ

The Middle East venture capital market is surging off the back of a slew of recent high-profile exits. As investors scramble to find the region’s most promising ventures, we investigate an emerging start-up scene looking to overcome the odds in Iraq.

In recent months, attention has turned to the Middle East’s growing technology space. Following a number of recent success stories from those who have taken the plunge into Iraq, there has been a swell of interest among high-net-worth individuals, institutional investors and middle-class professionals alike, who increasingly see opportunity for new initiatives in the region. Boosting these prospects, a growing number of angel investor groups and regional corporations setting up venture arms have diversified the sources of financing available – a marked change for the contemporary investment climate.

‘Three years ago, there were really only three VC firms in the Middle East and maybe two or three corporate VC arms,’ says Abdullah Mutawi, head of corporate commercial at Al Tamimi. ‘There had been a few eye-catching exits involving regional companies, but you couldn’t call it a particularly prolific or active regional ecosystem.’

That all changed in 2017, when Amazon made headline news with its competitive acquisitions of Dubai-based e-commerce platform Souq for $580m. Then, in early 2019, Uber bought Dubai-based transportation network company Careem for $3.1bn, marking the largest tech start-up exit in the Middle East to date.

‘Now the space is suddenly getting flooded with cash and the net is being cast ever wider to countries like Egypt, Syria and Iraq in search of the best returns,’ adds Mutawi, who has worked on dozens of venture deals in the technology space as a lawyer while also acting as an angel investor to start-ups across the region for the past decade. In 2016, he co-founded Dubai Angel Investors, a venture capital fund that now holds a portfolio of 18 technology companies, seven of which are domiciled in the Middle East.

‘Across the Middle East there is a lot of untapped skill among younger people, many of whom are now finding opportunities to work in technology, whether by developing new tech or working on the localisation side, by converting Western business models to fit the needs of the region,’ he explains.

‘It is a great way to escape being trapped in a job market that is dominated by the state and marked by high levels of unemployment. As long as you have a computer and the internet, you can plug in to a project anywhere.’

With one of the youngest populations in the world, Iraq could present a rich source of talent for investors with a high tolerance for risk.

‘There is a generation of young entrepreneurs who are hungry for opportunities,’ adds Ahmed Tabaqchali, chief investment officer of Asia Frontier Capital’s Iraq Fund and an adjunct assistant professor at the American University of Iraq, Sulaimani (AUIS).

‘There are some wonderful start-ups and entrepreneurs and the interest among the younger generation in non-traditional paths to employment is growing rapidly.’

BUILDING THE PLATFORM

While still early days, there are already a number of promising start-ups emerging in Iraq. These include grocery delivery company Mishwar, which has secured funding from angel investors, food delivery apps Brsima and Lezzoo Eats, Kurdish music-streaming app AWAZA, e-commerce platforms Shopini, Miswag and ShopYoBrand, tourism app Bil Weekend, and logistics provider Sandoog.

A number of technology incubators and co-working spaces have also started sprouting up in Iraqi cities, notably The Station in Baghdad, as well as re:coded, Tech Hub and Five One Labs in the Kurdistan region, where institutional support is also offered by the AUIS Entrepreneurship Initiative. There are promising signs, but still a long way to go.

‘The education system has not traditionally been oriented towards problem-solving, there are negative attitudes towards failure that put people off trying something new,’ says Pat Cline, director of the AUIS Entrepreneurship Initiative and senior lecturer at the university’s business department.

‘Add to that, until very recently, there were no real entrepreneurial role models for young people in Iraq, and it can make it tough for people to understand what building a business really means. I still encounter people who tell me they want to start a tech business so they can work for three hours a day while having a good standard of living.’

Even those who understand the commitment involved will find it difficult to grow businesses at speed. One of Cline’s former students, Hevi Manmy, started Brsima while at the AUIS. The food delivery app has grown into one of Iraq’s biggest start-ups, but the journey was not an easy one.

‘It’s tough to get a product built in Iraq. Manmy had this great idea, but when it came to building a team that could deliver it, he hit real technical challenges,’ explains Cline.

‘There just isn’t the depth of coding and tech talent in the market to support a lot of these businesses. You have to take the long view and accept that the local market will take at least a few years to hit a level of maturity that can allow it to really grow.’

To help address this technical skills gap, organisations across the region have taken to evangelising the need for coding skills, while working on upskilling would-be entrepreneurs. For example, Kuwait-based Barmej (the Arabic verb meaning ‘to programme’) is on a mission to teach coding skills in Arabic, seeking to help young and displaced communities in countries like Syria and Iraq who lack the English language skills needed to follow online tutorials and courses.

Alice Bosley (left) and Patricia Letayf (right), co-founders of Five One Labs

In Iraq itself, many of the most successful start-ups have passed through incubator and co-working space operator Five One Labs. Based in the Kurdistan region, Five One Labs launched in 2017 to help internally displaced people (IDPs) find new opportunities through entrepreneurship. It has since branched out to become an incubator for all, offering training and mentorship delivered by leading entrepreneurs from the US and the Middle East, though it continues to run regular training programmes in refugee camps and keeps IDPs as its North Star.

At Five One’s incongruously modern offices in Erbil and Sulaimani, visitors are greeted with yellow-painted walls that ask, ‘What’s your big idea?’. It all looks very unlike the war-torn, left-behind Iraq commonly seen on the news. And that is the whole point.

Stories about corruption and setbacks that keep getting picked up in the media are important, but there is more to Iraq. It is important to build awareness of the high-fliers who are doing new things, but also of the very real shift that is taking place among the interests, ambitions and demands of young Iraqis,’ says Tabaqchali.

‘Ultimately, disassociating the country from the perception that it is a failed state with no hope for the future will have a huge impact on the way investors and businesses see the country, while helping to reshape the way Iraqis themselves think about work and society.’

FINDING FINANCE

But changing perceptions alone will not help to grow Iraq’s start-ups into viable businesses. In the coming months, Five One Labs will turn its attention to one of the biggest problems entrepreneurs in the country face: finding investment.

‘We are only just starting to hear people talk about investment opportunities and paths to market,’ says Patricia Letayf, co-founder and director of operations at Five One Labs.

‘While there is a lot of money in Iraq, it is not being deployed as investment capital. International investors are starting to show some interest, but it’s also critical for us to have local buy-in. We need to make sure we get investors from Kurdistan signed up before we go out to the rest of the world. There is no reason why we can’t grow the space locally. It has already happened in places like Palestine. If one frontier market can find ways to connect home-grown angel investors to businesses, why can’t Iraq?’

Until that happens, entrepreneurs approaching the small number of angel investors active in the local market will find that even small investments will come with demands for high equity – such is the reality with a high-risk profile and a limited number of success stories to point to.

‘The number of people willing to finance these businesses is so low that those who are prepared to put up cash can demand a greater return,’ says Cline.

‘That makes entrepreneurs sceptical of finance, leads to fewer investable projects, and reduces the interest investors have in the space. That is a problem right now, but even in the last two years I’ve seen big changes. Will there actually be a VC industry making quarter-million-dollar investments in Iraq? Absolutely. It’s just a question of how long it will take.’

Al Tamimi’s Mutawi is even more bullish, pointing to a changing landscape in other parts of the Middle East as inspiration for what Iraq’s future may hold.

‘Sophistication is growing on both the investor and entrepreneur side. In Dubai, it is now much more common to see Silicon Valley-style financings for even early-stage entrepreneurs,’ he says. ‘While businesses in less mature markets will of course be asked to give up more equity, what we are seeing is savvy entrepreneurs across the region realising that they can wait it out. If you have a really good product or idea, you can always turn away bad offers and get money from more experienced and sympathetic investors further down the line.’

However, those interviewed as part of this report feel that there needs to be more of an effort to educate entrepreneurs and investors on how to strike a balance that is mutually beneficial, particularly given the nature of Iraq.

‘We need more of a push to engage with potential investors and explain that the terms they are demanding are not good for either side, but we also need to acknowledge that the VC scene anywhere in the world places a lot of responsibility on entrepreneurs to present investors with accurate data,’ adds Cline.

‘If the VC has to do your homework for you, you’re sacrificing a lot of your bargaining power. Among the things we are focusing on at AUIS right now are crash courses in accounting, legal and business issues, so the financials and the books of start-up companies are good to go.’

If the aforementioned balance can be found, research by The Legal 500 suggests that there is a willingness to put cash into Iraq in the right circumstances. Of those surveyed as part of this report, 40% said that the main incentive for investing in Iraq at present was a lack of strong local competition. Finding a unicorn company may be a way off yet, but for those start-ups that are able to establish themselves in niche industries – outwardly, at least, there appears to be a positive disposition towards helping them take the next steps.

BARRIERS TO ENTRY

Antiquated laws and regulations – many dating from the 1970s – in conjunction with a bureaucracy that is not used to moving at speed, represent additional major challenges for Iraq’s start-ups. ‘There is a rather onerous list of requirements to incorporate and maintain a company in Iraq,’ says Tabaqchali. ‘This places huge time and resource demands on start-ups, at least those that want to expand away from the shadow economy and enter the mainstream. Improvements to these legal processes are just as critical as anything else for Iraqi businesses to succeed.’

Difficulty dealing with the government was the most frequently cited barrier to success for those companies operating in Iraq, with 35 respondents having encountered issues here. Whether through a lack of willingness or sophistication, the legal frameworks, and those tasked with administering them, continue to cause issues for business.

‘While businesses in less mature markets will of course be asked to give up more equity, what we are seeing is savvy entrepreneurs across the region realising that they can wait it out.’

Abdullah Mutawi, Head of corporate commercial, Al Tamimi

While more established companies are able to turn to external law firms for help in understanding the local licensing regimes (42 respondents) and dealing with government departments (38 respondents) – among the most widely sought areas of assistance according to The Legal 500’s survey, – finding a solution for start-ups can be more trying.

‘When I was first trying to set up Brsima, as there is no e-commerce law in the Kurdistan region of Iraq, I was basically told the business did not constitute a company. I spent days at the registration bureau arguing with them until they had agreed what a registration document for that type of business might look like,’ says Manmy.

Adds Cline: ‘Those trying to register an e-commerce business will be told they are basically operating a shop, which means they need to have a physical space registered in all the places they want to trade. That makes no sense to an e-commerce provider that wants to operate with a light footprint rather than opening premises all over the region.’

The upshot is that for start-ups in Iraq, taking a deliberate, pragmatic approach is oftentimes the only pertinent path. Consider food delivery business Lezzoo Eats – another fledgling company to emerge from the Five One Labs programme – that ran afoul of local licensing laws when trying to incorporate using an English name.

‘The use of the English words in a company name makes the registration process more difficult and expensive and follows a different process,’ explains Astara Maiure, training and business development manager at Five One Labs.

‘You also can’t just pick a random name you think is cool, because the authorities won’t allow words that are not in the dictionary. You probably wouldn’t get away with Google, and Hulu would be ruled out entirely!’

The difficulties founders face when registering their businesses are compounded by rules that do not allow for blanket registration covering the whole country.

‘There are a few specific types of trade you can register as being in a particular city, but you need to re-register if you want to expand operations into a new location. You can apply for a broader type of registration that will allow you to operate as a company across a number of locations, but it is significantly more expensive and will only cover you in one region,’ explains Maiure.

Even then, businesses can struggle to trade in a new city. Bureaucratic processes are not yet fully digitised and different branches of government do not always communicate effectively.

‘Even if you are technically registered to operate across a region, you can never be sure the authorities in a different city will have received a record of it,’ says Letayf.

‘The Deputy Prime Minister’s Office is pushing for more digitisation and moves are underway, but making it happen requires a developed technocracy.’

A tech mentor advising entrepreneurs during the Iraq Innovation Hackathon

The extent to which start-ups can protect their IP is the final piece of this bureaucratic puzzle, and one that businesses of all shapes and sizes are encountering. Of those surveyed for this report, 28 respondents cited difficulties with protecting intellectual property rights as a chief difficulty with investing in Iraq.

‘IP tends to be an afterthought, because no one really believes it can be protected. The widespread belief is that protections are costly to obtain, and if someone ever did infringe, it would be a nightmare to litigate,’ says Letayf.

‘We have brought in lawyers to talk to the entrepreneurs and explain how the process works, but there remains a general reluctance to share ideas due to a lack of trust and a perpetual fear that someone is going to steal those ideas.’

While concerns over protecting IP scored highly among the GCs and businesses surveyed for this report and are anecdotally among the biggest concerns for entrepreneurs and founders, below the surface there may be a more pressing set of challenges.

‘IP tends to get looked at as trademarks and patents. Trademarks are very well protectable around the region, while patents are not such an issue for tech companies anyway because they are building consumer-facing platforms rather than patentable technology. Unless you’ve invented something really novel, you’re not going to get much of a patent anyway,’ says Mutawi.

‘The more interesting part of IP for me as an investor and a lawyer advising emerging companies, is how to protect business secrets so employees can’t run off and use those secrets – whether in the form of processes, business plans, or financials – to set up a competing business. If you take shares in a start-up anywhere in the region, you want to be sure that it has the right to exploit its intellectual capital via the product, processes and systems that have been built into it over time.’

He adds: ‘While protecting trademarksand patents is of course important, I would advise any investor to take a closer look at the protections around business secrets. That’s where you’re most vulnerable. You need to create a different type of IP protection that works through clauses in the employment contract stating that everything an employee does or produces in the company permanently belongs to the company.’

AN IRAQI CHAMPION?

Start-ups in Iraq are still to some extent an imitation game. While that happens in even the most sophisticated markets, breaking through imitation into genuinely new technologies will be the true test of the ecosystem’s maturity. As Mutawi puts it: ‘When investors in the region see something like that, they think this isn’t just a region where someone takes Uber, turns it into a local version and sells it back to them. However, the rapid spread of the VC movement in the Middle East will encourage more and more people to give it a shot, which means it will surely only be a matter of time.’

PAYMENT SOLUTIONS

Once financing is secured, start-ups in Iraq must find ways to make money. Like many developing markets, the vast majority of Iraqis are only able to deal in cash. That means start-ups are unable to simply copy the Silicon Valley playbook.

‘All start-ups need something in their business plan to clarify how they are going to get around the cash-based economy problem, or investors are not going to touch them,’ says Patricia Letayf, co-founder and director of operations at Five One Labs.

‘If you look at e-commerce companies in Iraq, they are essentially ordering goods on behalf of other people and collecting cash on delivery. There will inevitably be a failed order rate, which very much increases the cost of doing business. That’s one of the unique aspects of the local start-up scene – the most successful operators are not necessarily the ones with the best tech, but the ones that have been clever at finding solutions around the cash problem.’

Telecoms businesses are likely to play an important part in this development due to their widespread presence in emerging markets. In countries that lack fixed-line infrastructure, people rely on mobile providers to stay in touch. Although Iraq has one of the lowest levels of smartphone penetration in the world, its three main mobile networks operate in more physical locations than any other single private entity in the country. That makes their retail outlets ideal places for payment processing.

Telecoms providers are also helping to plug the gaps in Iraq’s financial infrastructure by bringing new services to the unbanked and underbanked. Kuwait-headquartered telecoms provider Zain has been operating in Iraq since 2003 and is now the country’s largest mobile operator by customer numbers. A long-standing supporter of the local start-up scene, the company launched ZainCash in 2015, offering Iraqis a mobile money transfer, mobile wallet and bill payment service licensed by the Central Bank of Iraq. The company’s other initiatives include a mobile money platform partnership with technology provider eServGlobal and a prepaid Switch Mastercard that can be topped up through ZainCash wallet.

These services, notes Letayf, are already having a marked impact.

‘I visited Berlin with a group from Iraq recently and every single person from Baghdad and Mosul came with Zain pre-paid cards. What this does is allow people to venture beyond Iraq in ways that were previously very difficult. That makes a huge difference, and I am seeing a lot of start-ups looking to find ways of harnessing these services to meet the challenges they face.’

Anwar El Khatib, General counsel, Oman Insurance Company PSC

El Khatib shares his experience on the realities of setting up and doing business in Iraq, detailing the difficulties of navigating a complex and disparate regulatory regime.

My experience in Iraq is limited to Erbil, in the Kurdistan region. There, they have their own regulations and try to distinguish themselves to some extent from the rest of Iraq – something which is especially true in the insurance sector.

Insurance companies are regulated under federal regulations in Iraq. In Erbil, they tried to have their own set of regulations – but they weren’t very clear, rather, it was one page of instructions instead of an actual law. It was a bit weird!

We tried to incorporate and open a branch in Kurdistan at first, but that never happened, largely due to a stipulation that required a large amount of money to be deposited in one of their banks as a guarantee. It had to stay there untouched, with no interest paid on it and no clear stipulation on why that had to be there. It could have been to protect the insured in the event of insolvency, but that was not clear. Following that, we attempted to acquire an existing incorporated company. It was easier in a sense because the company was already incorporated, had capital and we were very close to closing the deal. In the end, we decided not to proceed – going through the process of approvals to acquire the shares in the company and become a major shareholder, nothing was clear and everything was a struggle.

The regulators did not know how to deal with a foreign entity coming to acquire shares in a company that already exists. It’s kind of novel to them and they really didn’t seem to know what to do in the situation. The company was already licenced by the federal regulator. It had to report also to the Kurdistan regulator, which made it very confusing.

What was particularly difficult was trying to attain clarity on how to proceed – even a lot of the law firms had no idea. I ended up meeting the regulatory board over there – it was totally unsophisticated and we did struggle a lot – but I met with them and was able to understand what could and could not be accomplished.

One of the most surprising things about this whole process was that I did not see much appetite for developing the regulatory capacity. Perhaps it was a consequence of the sector. Insurance, and perhaps by extension, finance, did not appear to be something they had much exposure to.

Zeid Uteibi, Head of legal – MENA, Hikma Pharmaceuticals

Having previously worked in Iraq during the mid-noughties for Orange, Uteibi discusses how the business environment is evolving from the perspective of his new role at Hikma Pharmaceuticals.

I am the general counsel for Middle East, North Africa and emerging markets. I have a head of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) and Iraq that I have appointed, but I supervise the agreements or arrangements or acquisitions that we do in Iraq. I supervise our operations in terms of how we get money out of Iraq, compliance arrangements, and our technical and behavioural investigations. A lot of legal issues arise when you are in Iraq.

Going back further, I have very good experience in Iraq. I started covering the GCC area with Orange then became MENA legal lead, which covers Iraq also. I know Erbil, and I’ve known Iraq from the era where it was sheltered, up to now. I know how the supply chain moves, what is acceptable, what is the difference between Erbil and central government in Iraq, what is practical and what isn’t.

I joined Hikma in 2013 as head of Iraq and the GCC. We started seeing the business models for pharmaceutical companies in Iraq, the way the supply chain works, how the structures work, how the investment criteria work.

Pharmaceutical products are basically the biggest need behind food and milk in Iraq – so for us, it’s a big market. Iraq is well educated on health matters. They will go to doctors and discuss and research new drugs. You have a market there. A potential market, because it is now mainly tenders. But that will change.

A major challenge for multinationals is the UK Bribery Act and the ABC clauses. You need to ensure you are compliant with regulatory requirements in the UK, especially for Hikma as a UK-listed company. The SFO reviews a lot of the work done by companies active in Iraq. So you have to have a very sharp eye when it comes to these challenges in Iraq.

There is clear political influence that needed to be properly managed as well. We had some dilemmas with our employees, and even the employment side required certain arrangements to secure people on the ground.

You also have to be very prudent when it comes to business partners. Most of the distributors in Iraq will usually open companies in Jordan or Dubai, and they will offer to pay you in Dubai or Jordan. But under the new UK anti-money laundering act it is illegal to do this unless you are established substantively. That means the most important thing is to make sure you have an audited and credible business model to ensure compliance with the regulatory requirements.

The final frontier?

Investing in post-conflict markets is a difficult proposition for even the most experienced and well-capitalised investors. The underlying challenges and inherent risks – not to mention uncertainty – are often enough to dissuade all but the most bullish of investors. But the potential rewards on offer for those with an appetite for risk can be significant. However, as many have discovered, Iraq is a market where the risks and rewards are inextricably linked.

‘As the economy develops the market will grow and if you get in early enough, you can make enormous returns. Of course, that doesn’t come without enormous risks. But the really attractive part is that Iraq is a post-conflict economy. As the country goes from destructive and non-productive war towards economic activity, there is a huge peace dividend to be had,’ says Ahmed Tabaqchali, chief investment officer of the Asia Frontier Capital Iraq Fund.

Now, the small print.

‘Iraq has had every conceivable conflict non-stop since the 1980s. Nearly 40 years of destructive conflict, civil war, dictatorship – you name it. That means the time to realisation is going to be longer. Other markets have emerged from conflict, but not from such a sustained and deep conflict. It really requires patience. The returns will come, I am sure, but we are not looking at easy wins here.’

Countries like Iraq – developing nations which are yet to meet emerging market status because of size, risk and liquidity issues – are typically termed as frontier or pre-emerging markets. While there is an expectation that in time they will develop into more stable investment markets, the risk profile and nature of the investments – often long-term and with high barriers to entry – make them unattractive to investors without the requisite country knowledge and risk tolerance.

‘There are all sorts of challenges that come from [Iraq’s] lack of development, starting with the legal challenges and the day-to-day operations, how to conduct them and the high costs of operating there,’ says Mohamed Hawary, director of investment for MENA at GroFin, an investment fund manager specialising in the finance and support of small and growing businesses.

‘The upside of that is that when I look across the region, I see that Iraq has the most investment potential simply because it’s coming from such a low base. Any degree or period of stability will make a big difference and you will see growth in a relatively short space of time.’

That low base from which Iraq is rebuilding from was the most commonly cited reason those surveyed for this report gave when asked about their main incentive for investing in Iraq, with 40% pointing to a lack of strong local competition. That said, many anticipate an extended investment horizon before the prospect of any real rewards materialise.

‘It’s impossible to put a date on when returns will come or to set horizons, but what we can do is look at other post-conflict societies and track against their development. Nothing is a perfect guide, but you can make predictions,’ says Zaab Sethna, partner at Northern Gulf Partners, a frontier-focused investment firm specialising in Iraq.

‘The country may be impoverished now, but it has the capacity to very quickly raise itself into the ranks of the middle-income economies and eventually be a rich country. The country has been cut off from the world and subjected to every bad idea known to mankind in the twentieth century. They are also starved of international links – they’ve been cut off from the outside world for a generation.’

RESOURCE RICH

It will come as little surprise that most international investors are still looking to the oil sector. Iraq has 12% of the world’s total oil reserves and is second-largest crude oil producer in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), after Saudi Arabia. It is also the fourth largest exporter of oil (holding the fifth largest proven reserves). Oil production has doubled in the last decade, creating demand for exploration and production companies, as well as oilfield service providers.

‘Most investments are concerned with the resource advantages in Iraq, most obviously in gas and oil as well as downstream. The big and major investments are currently downstream,’ adds Amar Shuba, partner at Management Partners.

‘All of the international oil companies are here already. The big foreign direct investments which are supposed to happen are all in downstream. That is a long and tedious process that will take time.’

Many of the 90 fields that currently exist in Iraq are not operational or need significant investment to produce efficiently. It’s a similar story for the country’s gas infrastructure: Iraq has the potential to be one of the largest gas producers on earth, but around 70% of it is burned on discovery due to a lack of infrastructure to capture and transport it to market. Yet despite there being a glaring need for investment, a number of those who we spoke with reported significant barriers for international companies to overcome.

‘As a general rule, if it’s a massive, too-big-to-fail infrastructure project that can’t go wrong then international companies are not precluded from bidding for it – there is no one else who can provide those services,’ says Paul Bailey, founder of Devonport Capital, a specialist lender that provides bridge-financing to SMEs operating in Iraq.

‘But for a smaller contract, there can be incredible pressure to use local contractors who are sub-optimal and poorly qualified. It’s poorly focused politically, and it’s never the best value or best qualified candidate who wins a bid but the best connected.’

Reflecting the regional divisions that still mark Iraq, oil contracts in the KRG were structured very different from those in the south. While operators in Kurdistan have entered into production sharing agreements with the government, giving investors some degree of title over the oil in the ground, companies working in Federal Iraq – including those based in the super-giant Rumaila field, considered to be the third largest oil field on earth – are operating under technical service contracts that grant them a fixed percentage of the exploitation. Unfortunately for Iraq, these contracts, and the formulas used to determine returns, were poorly designed.

For investors who aren’t willing to take on the risks associated with projects in oil and gas in Iraq, they will largely struggle to gain exposure to oil and gas through other investment vehicles.

‘There is no company related to the oil or energy sector that trades on the Iraq Stock Exchange, which is a bizarre anomaly given that it is the huge driver of the economy,’ says Senath.

‘That’s a legacy of the centrally planned economy of the Saddam era, where oil was something that was highly controlled by the state. The government is trying to encourage the development of Iraqi private sector companies in the oil space; it is happening slowly and there are some decent ones, but still none of them are listed and it remains state dominated.’

CASH POOR

Despite not having exposure to oil and gas, Northern Gulf Partners’ investment fund, Iraq Investment Partners I (IIPI) was the world’s best performing emerging markets hedge fund according to data compiled by the BarclayHedge Global Hedge Fund database. In the coming years, Sethna sees further opportunity for investment into Iraq’s stock market.

‘The figure we like to use as a benchmark is the total market capitalisation of the stock exchange to the gross domestic product (GDP) of the country. Iraq’s market cap today stands at around $11.7bn, which is under 6% of the country’s GDP [of roughly $200bn],’ says Sethna.

‘The closest comparable country in terms of population, geography and reliance on oil is Saudi Arabia, which has a market cap to GDP ratio of 75%. That shows you there is tremendous potential for growth in Iraq. That’s the story we are investing in.’ That story is resonating with an increasing number of investors in recent years says Grofin’s Hawary, who reports an uptick in interest for Iraqi investments across the board.

‘When we first went there, we didn’t have a lot of investors at all. But now we are definitely getting more and more enquiries and seeing more interest. It is gaining momentum, especially in the last two years,’ he says.

‘Right now probably around 15% of the portfolio covers Iraq but it is growing fast. We think that in a couple of years it can grow to around 25% of the total portfolio.’

But while increasing numbers of investors are considering investing in Iraq, a dearth of available capital remains one of the biggest impediments to progress – particularly for small companies.

‘There are companies which are market leaders; there are families that have been in business for generations; there are young people with start-up ideas. What they are all starved for it capital. There is no source of financing in the country. The banks aren’t lending and the government has little knowledge of the private sector,’ explains Sethna.

‘In Iraq, high liquidity is essential. Because there is no credit system and so forth, most businesses carry a lot of cash. As a result, many function very inefficiently,’ adds Tabaqchali.

‘That means there is a huge amount of wealth to be unlocked once they start to function differently. If you unlock all this cash once the country transitions toward a market economy, it will open up enormous opportunities.’

International businesses have had their own issues with acquiring capital for use in Iraq too, which has made investment difficult – or impossible – for many prospective investors. But a lack of available capital and an inability to carry out the required due diligence in a cost-effective manner has spelled opportunity for some businesses in Iraq.

‘We found the most lucrative thing we did was short-term loans. We had our own cash in the bank and found that sensible companies from the UK or US would win contracts from one of the oil majors to supply parts in places like Kazakhstan, Abu Dhabi or the Gulf of Mexico. Then the oil major suddenly decides it needs to be in Iraq and asks the supplier to work with them. When those suppliers go to the bank and show them a contract for services in Iraq they suddenly find there is no funding available,’ says Bailey.

‘If you’re looking for $200m for a 20 year loan the bank will take the time and effort to educate themselves about it, but when you’re a smaller supplier asking for $500,000 for 90 days as a bridge payment then it’s not worth the time and money for the bank to fund it. They won’t make enough off it to cover the costs of scrutinising that loan – the amount of paperwork you need to extend a small loan in Iraq is similar to a loan ten times the size elsewhere. The risk to reward ratio is so skewed that a bank will just turn them away.’

INVESTMENT DIFFICULTIES

With due diligence on major investments often falling under the remit of in-house counsel, those who participated in our survey were well placed to comment on the current procedures used by those currently – or considering – the difficulties presented by investments in Iraq. It was clear that one of the biggest challenges investors and businesses faced was the opacity of the Iraqi market.

‘Ten years ago, the idea that someone would pay outside counsel for advice was anathema to an Iraqi business, even a very large one,’ says Bailey.

‘Now, both sides of the transaction have international lawyers. More and more, lawyers are being seen as a value add in terms of clarity and professionalism, and not a leaching cost.’

That notion aligned with the results of our research, with 77% of those having engaged a lawyer on Iraq-facing matters in the past 12 months, with help establishing an office (52 respondents) and tax related advice (47 respondents) being the two most common reasons to seek outside counsel. While the country’s undeveloped arbitration laws were only cited by 5 respondents as a major concern, it was clear from those we spoke to that dispute resolution remains a big issue.

‘When I worked in private practice, the position was always that you can’t really do arbitration in Iraq’ says Mohamed el Roubi, general counsel at GardaWorld International Protective Services. The country is still not party to the New York Convention so you either have to do it in Iraq or find places where there is a bilateral or multilateral agreement to feel secure.’

The New York Convention has since been ratified by the Cabinet in Central Iraq but needs to be approved by the parliament in Federal Iraq in order to be applied across the whole country. The question of when Iraq will become a signatory to the New York Convention is a huge issue for international investors.

‘Although the New York Convention has been ratified we are still waiting for it to become effective. Until then, businesses operating in the country will face uncertainty,’ explains Simon Nai, deputy manager of legal and audit department at CNOOC Iraq.

‘While there are ICC cases in progress, businesses generally lack practical examples when it comes to arbitration against an Iraqi company or the national government, which makes it difficult to understand how strong the enforcement mechanisms are.’

In the meantime, a number of initiatives are underway to help improve business confidence, including a network of specialised commercial courts established in 2015 to help provide alternatives for resolving resolve disputes involving international investors. But Mais Abbas Abousy, who worked to help establish the courts in her role as attorney-adviser at the Commercial Law Development Program, says that businesses are failing to make the most of the opportunities they provide.

‘The biggest test is ultimately whether the system can be sustainable. We have seen that it has the potential to be – I know of many cases in the courts rule in favour of the non-Iraqi party. However, the question is not so much whether protections in Iraq are strong, but whether the international party wants to take it to court,’ she says.

‘Many companies do not utilise the service that everybody worked very hard to establish because they’re afraid of the impact it could have on their reputation or the cost to their operations in Iraq. That has nothing to do with the courts themselves – from what I’ve seen, the commercial courts of Iraq are as strong as any others in the region.’

A BRIGHTER FUTURE

Despite there being a host of challenges remaining for Iraq to overcome, there remains reasons for optimism, particularly when current progress is contextualised against the difficulties which plagued Iraq even a few years ago.

‘Iraq is going through two transitions at the same time – from war-torn to post-conflict and from centrally-planned to free market. It’s fiendishly difficult to manage these two transitions at the same time,’ says Sethna.

‘But what a lot of people don’t realise that per capita GDP in Iraq has more than trebled in the last ten years. It’s out of the impoverished zone and heading toward middle income.’

Whether that will prove sufficient to attract further investment in the short-term remains to be seen. But with positivity emanating and an increasing number of success stories to point to, as well as improving investor protections and international links, the point where the risk profile of Iraq becomes more tolerable for investors appears to be approaching.